The most common risk factor for vulval cancer is infection with the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV). HPV is a common sexually transmitted infection that causes most cases of cervical cancer and about 70% of vulval cancers. There are many different types of HPV (not all of them cause cancer) and your body can sometimes clear the virus by itself, so not everyone who is exposed to HPV will get cancer.

HPV is transmitted by skin-to-skin contact, usually during sexual contact (including oral and anal sex). Practising safe sex by using condoms can help prevent the spread of HPV. However, the best way to prevent HPV infection is to be immunised against it before you become sexually active. A vaccination is available in Aotearoa New Zealand for boys and girls free of charge. Read more about HPV and the HPV vaccination.

Other risk factors for vulval cancer:

- Age – your chance of developing vulval cancer increases as you get older.

- Smoking weakens your immune system and increases the risk of many different cancers including vulval cancer.

- Immune deficiency – your immune system is designed to prevent infection and stop cancer from growing. People who have a weak or deficient immune system are more likely to get vulval cancer. Some of the more common causes of immune deficiency are medical treatment with steroids, organ transplantation, or treatment for another type of cancer and HIV.

- Lichen sclerosus is an autoimmune disorder (meaning your immune system is attacking healthy cells) that causes irritation, swelling and redness. It can occur in any area of skin but usually on the labia or vulva in women. The condition can usually be well controlled with steroid cream but it does increase your risk of vulval cancer – especially if it's not treated.

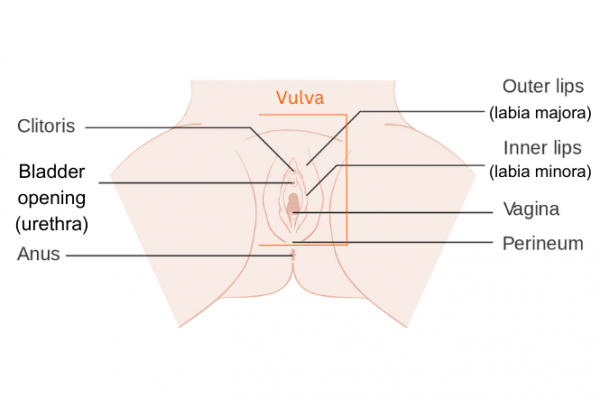

The image below shows the parts of your anatomy included in the vulva.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons