Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

Also known as squamous cell cancer

Key points on squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

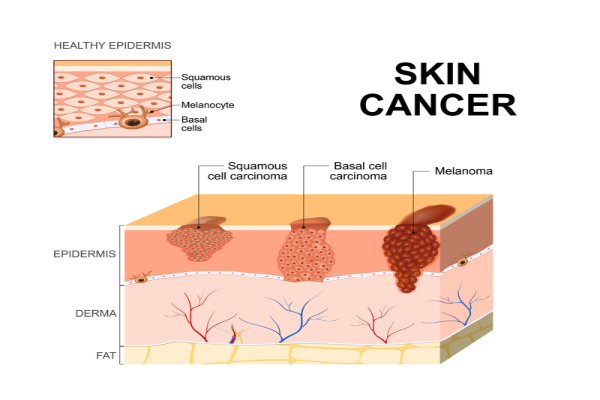

- Squamous cell carcinomas of the skin are a type of non-melanoma skin cancer arising from the flat, scale-like squamous cells that form on the outermost layer of your skin.

- Other forms of SCC can occur in other parts of the body, such as your lung, thyroid, oesophagus and vagina, but skin is the most common.

- SCCs often appear as a raised, crusty, non-healing sore, often on the hands, forearms, ears, face or neck of people who have spent a lot of time outdoors.

- 80% are found on the head and neck but they can happen in any areas exposed to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, either from sunlight or from tanning beds or lamps.

- They can be life-threatening and can spread around your body if not treated.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin is a common form of non-melanoma skin cancer. It develops in the flat, thin squamous cells that make up the middle to outer layer of your skin.

Image credit: Depositphotos

SCCs occur when there is damage to the DNA of squamous cells. This damage is usually from long term UV exposure from sunlight or tanning beds. However, it can arise from cigarette smoke, chronic wounds or scars. Normally, your skin keeps a healthy physical barrier by new cells pushing older cells toward your skin's surface where they die and are shedded (drop off). DNA errors (mutations) disrupt this orderly pattern and can trigger normal cells to grow out of control and incorrectly. Over time, these can lead to the development of SCCs.

You are at highest risk of developing a squamous cell carcinoma if you:

- are older

- have pale skin and burn easily

- have spent a lot of time outdoors for work or leisure

- have a history of sunburns, sunbathing or using sun beds

- live in a sunny climate

- have previously had a squamous cell carcinoma or other type of skin cancer

- have a condition or take medications that affect your immune system (immune suppression)

- have chronic wounds or scars, such as severe burns

- are a smoker.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin most often occurs on sun-exposed skin, such as your scalp, the backs of your hands, your ears or your lips. In rarer cases SCCs can occur anywhere on your body, including inside your mouth, on your anus and on your genitals. They can also develop in old injury sites or wounds that don't heal well.

Squamous cell carcinomas often appear as a raised, crusty, non-healing sore.

They may also appear as a:

- flat sore with or without a scaly crust

- new sore or raised area on an existing scar or ulcer

- rough, scaly patch on your lip that may evolve to an open sore

- red, sore or rough patch inside your mouth

- red, raised patch or wart-like sore on or in your anus or on your genitals

- new or changing sore on your skin that doesn't heal in 4 to 6 weeks.

You can see images of SCCs on the DermNet site(external link).

If you notice a change to or growth on your skin, make an appointment to see your healthcare provider straight away. They will assess the size, location and appearance of the growth. They will also ask you how long you have had it and whether it bleeds or itches.

If your healthcare provider thinks the growth may be cancer, they may take a small sample of tissue (a biopsy). The tissue sample will be sent to a laboratory and examined under a microscope to confirm the diagnosis. Your healthcare provider will let you know whether the sample shows any cancer cells or not, and will recommend appropriate treatment if necessary.

Treatment of a squamous cell carcinoma depends on its type, size and location and other factors, such as your preference.

Options include:

- surgical removal of the cancer (this is the most common treatment method)

- freezing it with liquid nitrogen

- topical therapies (chemotherapy creams)

- radiotherapy

- photodynamic therapy (a specialist treatment using light to activate creams).

If you have a squamous cell carcinoma, your healthcare provider will discuss treatment options with you. Treatment has a high success rate, as long as the skin cancer is found at an early stage. You may need to have more appointments to check for new lesions.

SCCs on high risk areas (including lips, ear or scalp), or in people with a weakened immune system, have a higher risk of spreading to other areas of the body so early detection and close monitoring is vital.

Read more about skin cancer treatment.

Apps reviewed by Healthify

You may find it useful to look at some skin care (dermatology) apps.

Most squamous cell carcinomas can be treated and cured. However, it's possible for these types of cancers to recur or for new skin cancers to appear.

Do the following to reduce the risk of new cancers occurring:

- Keep all follow-up appointments with your healthcare provider or skin specialist.

- Regularly check all your skin (from head to toe). If you see anything that's growing, bleeding or in any way changing, go and see your healthcare provider straight away. Read more about how to do skin checks.

- Protect your skin from the sun and avoid indoor tanning. This is essential to prevent further damage, which will increase your risk of getting another skin cancer.

- Avoid smoking.

Ways to protect your skin

- Avoid outdoor activities when the sun is strongest – between 10am and 4pm from September to April in Aotearoa New Zealand.

- Wear sunscreen and lip balm daily that offer SPF 30 or higher sun protection.

- Use sunscreen that offers broad-spectrum (UVA/UVB) protection and is water resistant.

- Put sunscreen and lip balm on dry skin 15 minutes before going outdoors.

- Put sunscreen on every part of your body that won't be covered by clothing. Reapply it every 2 hours if yo're swimming or sweating.

- Whenever possible, wear a wide-brimmed hat, long sleeves and long pants.

- Wear sunglasses to protect the skin around your eyes.

- Avoid getting a tan and never use a tanning bed or sun lamp.

See also sun safety.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin(external link) DermNet NZ

Squamous cell carcinoma patient information sheet(external link) British Association of Dermatologists, 2022

Squamous cell carcinoma(external link) The Skin Cancer Foundation, US, 2015

Skin cancer(external link) Cancer Society, NZ

Brochures

Radiation treatment(external link) Cancer Society, NZ, 2018

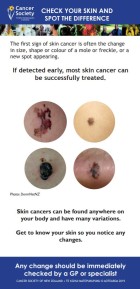

Take time to spot the difference(external link) Cancer Society of NZ

Apps

References

- Motley RJ, Preston PW, Lawrence CM. Multi-professional guidelines for the management of the patient with primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma(external link) British Association of Dermatologists, UK, 2009

- Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin(external link) DermNet, NZ

- Managing non-melanoma skin cancer in primary care – a focus on topical treatments(external link) BPAC, NZ, 2013

Clinical practice guidelines for keratinocyte cancer(external link) Cancer Council Australia

SCC guidelines update(external link) British Association of Dermatologists

Managing non-melanoma skin cancer in primary care – a focus on topical treatments(external link) BPAC, NZ, 2013

See our page skin cancer for healthcare providers

Brochures

Cancer Society, NZ, 2018

Cancer Society of NZ, 2014

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust.

Reviewed by: Dr Lottie Wilson, General Practitioner, Queenstown

Last reviewed: