Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can affect many aspects of your life. However, learning as much as you can about your condition, and getting the right help and support, can help you manage your condition and get the most out of life with COPD.

Find out how to take care of yourself so you can ease your COPD symptoms.

Quit smoking

The best way to prevent COPD getting worse is to quit smoking. Although damage done to your lungs and airways can't be reversed, giving up smoking can help prevent further damage and improve your breathing now. This may be all the treatment that's needed in the early stages of COPD but everybody, and in particular people with more advanced COPD, can benefit from quitting. Read some tips to quit smoking.

There are medicines available to help you quit smoking, eg, nicotine replacement therapy. There are also smoking cessation support services available to help you quit smoking if you need them. Talk to your healthcare team to find out what's available in your area.

- Quit card – a discount voucher for nicotine replacement patches, gum or lozenges.

- Quitline – phone 0800 778 778 for free advice and support.

- Visit the Quitline website(external link) for a free online Quit Coach, support, advice and information.

Using e-cigarettes will be less irritating, and therefore less bad than smoking, but vaping is not safe and the goal should be to stop smoking and vaping. If you don't smoke, don't start vaping as it may be bad for your lung health.

Have a COPD action plan

Ask your doctor or nurse to help you fill in a COPD action plan. An action plan is a written document that provides you with instructions and information on how to manage your COPD on a daily basis and also how to recognise and cope with worsening symptoms (flare-ups or exacerbations).

You can develop your COPD action plan with your healthcare provider and make a plan to suit the severity of your COPD and your preferences. At each visit with your healthcare provider you can review the plan and make adjustments as needed. Here are 2 examples of COPD action plans – choose the one that suits you.

Stay active

Regular exercise is important. When you exercise your muscles, including your breathing muscles, they learn to do more work with less oxygen. Often when people try to exercise and become short of breath, they stop exercising. However, the less active you are, the weaker your muscles become, making you even more short of breath over time – the more active you are the better. It's a matter of learning how to pace yourself and developing the confidence that you'll be okay.

Here are some tips for staying active

Choose an activity you might enjoy, eg, walking or swimming, and:

- start with small amounts

- begin at a comfortable pace – keep your breathing under control, so you can still talk if you wish

- take as many rests as you need

- go regularly, and increase your time/distance as your fitness improves

- aim for at least 20 to 30 minutes of exercise every day

- try muscle strengthening exercises at least twice a week, eg, using milk bottles as weights.

Before you start a new exercise regime talk to your healthcare provider. They may recommend strategies such as using a reliever/ ‘bronchodilator’ inhaler before you exercise to help you breathe more easily during exercise. Read more about home exercises for COPD(external link). If you're having trouble exercising because of shortness of breath, talk to your healthcare provider about a referral to a pulmonary rehabilitation programme.

Maintain a healthy weight

Losing weight if you are overweight helps to remove extra pressure on your breathing muscles so that you can breathe more easily. Talk to your healthcare team to find out how much weight you might be able to lose. On the other hand, if you are underweight, you will need better nutrition to provide more energy to help you breathe and provide more protein for your muscles. Talk to your healthcare team, your doctor or your dietitian to find out what's needed in your diet.

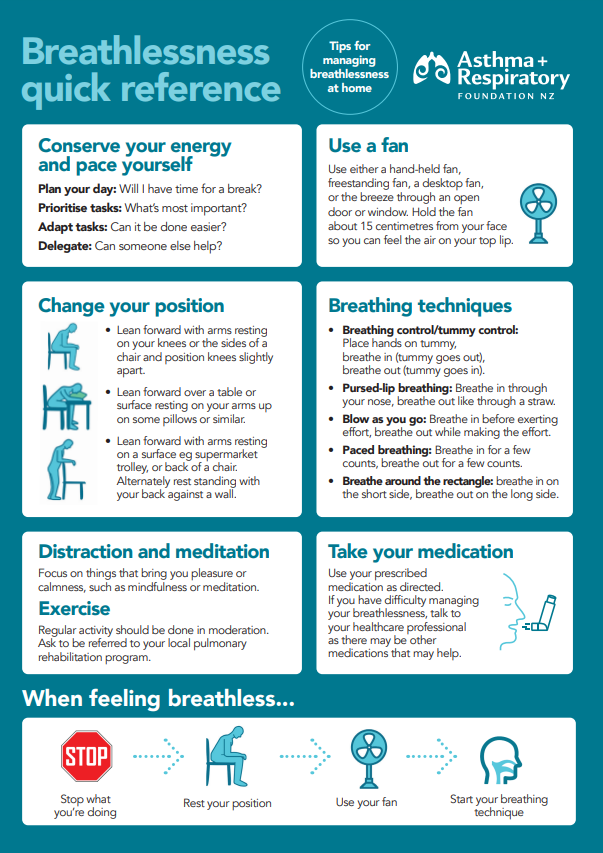

Improve the way you breathe

Correct breathing technique involves using your lower chest muscle (diaphragm) to take slow, deep breaths. This is called diaphragmatic breathing. Often people with COPD have a habit of shallow breathing and use the 'wrong' breathing muscles. This may be adding to your feelings of breathlessness. Practicing correct breathing technique regularly will help you to breathe more deeply and easily.

Your nurse or a respiratory physiotherapist can teach you how to do breathing exercises. Ask your healthcare provider for a referral to a respiratory physiotherapist or read more about breathlessness strategies for COPD(external link).

Some people may have excessive phlegm (mucus) from COPD. A respiratory physiotherapist can also teach you techniques on how to clear your phlegm effectively. These techniques help improve quality of life and your ability to exercise.

You may find certain cough medicines (expectorants for phlegmy cough) to be helpful, ask your healthcare provider.

A few people with severe COPD may benefit from taking longer-term antibiotics (macrolides). These should be prescribed or recommended by a respiratory specialist.

Attend pulmonary rehabilitation

Pulmonary rehabilitation is a group education and exercise programme usually run by your local hospital for 6 to 12 weeks. The programme aims to reduce your symptoms, increase your day-to-day functioning and improve your quality of life. It will teach you what you can do every day to stay well.

In the programme you will learn more about:

- COPD management

- exercise

- moral support

- quitting smoking

- eating well

- the COPD action plan.

Ask your doctor or nurse about attending a pulmonary rehabilitation programme or a general self-management programme. Read more about pulmonary rehabilitation.

Get your vaccinations

Having COPD increases your chances of getting chest infections. To help you lower this risk, make sure you are up-to-date with your vaccines.

- With the flu vaccine, you'll need to be vaccinated each year (about April) as the flu viruses change every year. The vaccine will help you avoid getting sick over the winter. The vaccine is free for people with COPD. Read more about the flu vaccine.

- There are 2 pneumococcal vaccines, Prevenar 13 (PCV13) and Pneumovax 23, which protect against different forms of the Pneumococcus bacteria. They protect you against bacteria that cause potentially severe chest infections and pneumonia. Talk to your healthcare provider about your eligibility for these vaccines as you may not be funded for them. Read more about the pneumococcal vaccine.

- Talk to your healthcare provider about getting the free COVID-19 vaccine and 6-monthly booster if you haven't already.

- A vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is recommended for people with COPD. It's available for people over 60 years of age, but it isn't funded by the government. Read more about the RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) vaccine.

- You may need an updated whooping cough vaccination (which comes together with a tetanus and diphtheria vaccination).

Have a warm, dry and smoke-free home

Having a warm, dry and smoke-free home helps you to control your COPD better and should improve your symptoms. Find some tips for a warmer, drier home. There's also help available for keeping your home warm and dry(external link).

Correct use of medicines

Medicines are used alongside self-care measures to help you breathe more easily and lower the chance of a flare-up. Using your medicines correctly is a crucial part of self-care for COPD. Inhalers won't work if they're not used properly. Spacers for the most commonly used reliever medications (eg, salbutamol and similar types and models of inhalers) are very important to use. Read more about COPD medicines and how to use them correctly.

Visit your healthcare team regularly

There are lots of people who want to support you so you can look after your COPD well. As part of your COPD management, it's important to visit your doctor, nurse or other healthcare team members regularly. This lets them check your disease progression and answer any questions you may have along your journey. They may refer you for a repeat spirometry test every 2 to 3 years. They can support you to look after your COPD well. Learn more about COPD support services.

Apps reviewed by Healthify

You may find it useful to look at some COPD apps, breathing apps, quit smoking apps and nutrition, exercise and weight management apps.