Frequently asked questions about ventilators

Also called a respirator or breathing machine

Key points about ventilators

- A ventilator is a machine that assists or takes over the work of breathing when you can't breathe enough on your own.

- There are 2 types of mechanical ventilation using ventilators – non-invasive ventilation using face or nasal masks, and invasive ventilation using a tube put into your wind pipe.

- Ventilators are used during surgery and/or if you're under anaesthesia.

- They can also be used if a disease, such as pneumonia or COVID-19, or a condition or brain injury means you can't breathe normally on your own.

- Ventilation gives your organs a chance to improve while medicines and treatments help you to recover.

A ventilator is a machine that assists or takes over the work of breathing when you can't breathe enough on your own, to make sure your body gets enough oxygen and that carbon dioxide is removed.

There are 2 types of mechanical ventilation using ventilators:

- non-invasive ventilation uses a face or nasal mask

- invasive ventilation uses a hollow plastic tube inserted into your wind pipe (trachea).

Ventilators are used during surgery, when you're under anaesthesia and if a disease or condition impairs your lung function and makes it difficult or impossible for you to breathe normally. This may be the case if:

- you have a severe infection, such as with pneumonia or COVID-19

- you have an injury to your brain

- you're unconscious and unable to breathe on your own.

Being on a ventilator doesn't heal you, instead it gives your organs a chance to improve while medicines and treatments help you to recover.

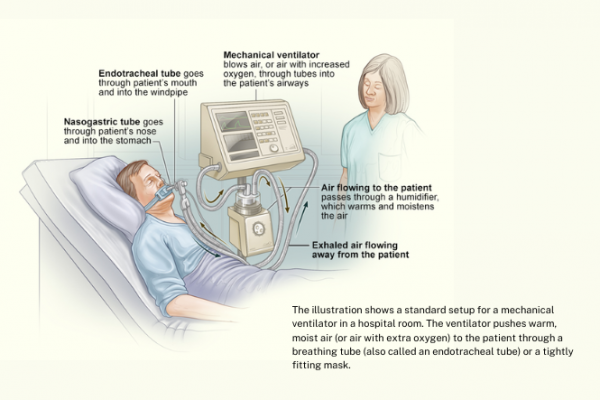

You are connected to the ventilator with either a face or nasal mask or a hollow tube (artificial airway/endotracheal tube) that goes in your mouth and down into your main airway (trachea). Ventilators blow air with oxygen into your airways and then your lungs. They also carry carbon dioxide, which is a waste gas, out of your lungs.

There are different settings that allow the ventilator to just assist your breathing a little or, if required, to “take over” the work of breathing fully.

For some people with long-term conditions that significantly impair breathing, non-invasive ventilation can be used at home and at least intermittently or throughout the night.

Image credit: NIH via Wikimedia commons(external link) (text from NIH added)

People on a ventilator due to an acute illness or because of having anaesthesia are monitored in an intensive care unit (ICU) or in an operating theatre. Anyone on a ventilator in an ICU setting will be connected to monitors that measure their heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure and oxygen saturation (O2 sats). Other tests that are usually required include chest X-rays and blood drawn to measure oxygen and carbon dioxide (arterial blood gases).

Members of your healthcare team (including doctors, nurses and physiotherapists) use this information to assess your status and make adjustments to the ventilator if necessary.

When using non-invasive ventilation with a mask during an acute illness such as a flare up of COPD or a severe COVID-19 infection there will be opportunities to briefly take off the mask and just use oxygen treatment temporarily.

When using non-invasive ventilation long-term at home it may only be required at night or from time to time and you will be regularly reassessed in a clinic setting.

Being on a ventilator isn’t painful, but the face mask or the breathing tube may cause discomfort, coughing or gagging. If you're on a ventilator you will usually be given medications, such as pain relief medicines and/or sedatives, to minimise pain, restlessness and anxiety.

Being on a ventilator with an endotracheal tube will affect your ability to talk and eat. If you're on a ventilator for more than just one day, instead of taking food by mouth you may need tube feeding (also known as nasogastric tube feeding or, less commonly, IV feeding or parenteral nutrition).

If you're on a non-invasive ventilator you can usually remove the mask for very brief periods and – while on oxygen therapy – talk and eat or drink as you're able.

During an acute illness, your healthcare team always tries to help you get off the ventilator as soon as possible. You may be on a ventilator for only a few hours or days, or you may require the ventilator for longer. This depends on many factors, such as how strong you are in general, how healthy your lungs were before you went on the ventilator and how many other organs are affected (such as your brain, heart and kidneys).

During an acute illness, depending on its severity, your healthcare team may change the treatment from invasive to non-invasive ventilation or vice-versa. If the invasive mode of ventilation needs to be continued, a tracheostomy is likely to be performed. A tracheostomy is a small cut in your wind pipe and insertion of a hollow plastic breathing tube to replace the breathing tube in your throat.

For people with more chronic (long-term) conditions such as muscular dystrophy, motor neurone disease or severe lung disease due to cystic fibrosis, the ventilator may be used for months or years.

- The main risk associated with using invasive ventilation is the risk of infection, as the breathing tube may allow germs to enter your lung. This risk increases the longer ventilation is needed and is highest at about 2 weeks.

- Another risk is lung damage caused by either the pressure or the repetitive opening and collapsing of the small air sacs (alveoli) of your lungs.

- The main risk with using non-invasive ventilation is pressure effects on the bride of your nose as well as some throat irritation.

'Weaning' is the process of taking you off a ventilator so that you can start to breathe on your own. People are usually weaned after they've recovered enough from the problem that caused them to need the ventilator.

- Weaning usually begins with a short trial. You stay connected to the ventilator, but you're given a chance to breathe on your own.

- Most people are able to breathe on their own the first time weaning is tried.

- If you can't breathe on your own during the short trial, weaning will be tried at a later time.

- Once you can successfully breathe on your own, the ventilator is stopped and the breathing tube is removed. You may cough while this is happening.

- Your voice may be hoarse for a short time after the tube is removed.

- Invasive ventilation may be changed to non-invasive ventilation using a mask for a period of time.

- If repeated weaning attempts over a long time don't work, you may need to use the ventilator longer term. In those situations, the breathing tube will be changed from the mouth to one inserted via a small cut in the wind pipe (trachea) called a tracheostomy.

Intensive care(external link) NHS UK

Apps

References

- Ventilator/ventilator support(external link) National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, US, 2022(external link)

- Mechanical ventilation(external link) American Thoracic Society, US, 2017

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust.

Reviewed by: Dr Roland Meyer, Specialist Physician, Respiratory and General Medicine

Last reviewed: