Osteoporosis | Kōiwi ngoikore

Key points about osteoporosis

- Osteoporosis (kōiwi ngoikore) is a condition where your bones are thinner and weaker than normal, which means they can break more easily.

- It affects more than half of women and about one third of men over 60 years, as well as some younger people.

- Ask for an osteoporosis check if you've had a fracture that happened more easily than it should, eg, after a slight bump or a simple fall.

- There are treatments that can slow the progression of osteoporosis and help prevent you getting broken bones.

- There are also things you can do to keep your bones healthy and strong and prevent osteoporosis from developing.

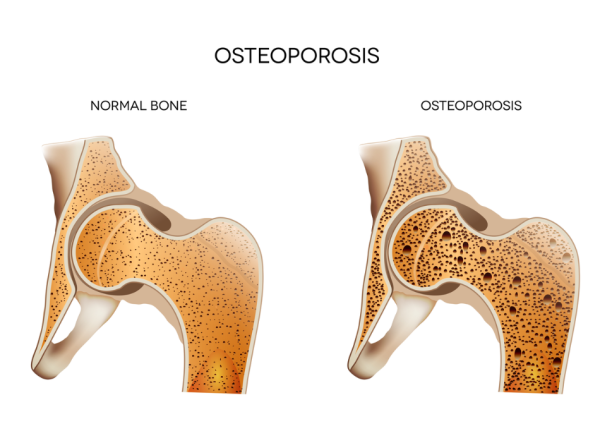

Osteoporosis (kōiwi ngoikore) is a condition where your bones are thinner and weaker than normal, which means they can break easily.

It happens because your bones lose important minerals and so they become less dense.

You may not know you have osteoporosis until you break a bone. Osteoporosis is the main cause of broken bones (fractures) in postmenopausal women and older men.

Fractures are most likely to happen in your hips, the vertebrae of your spine and your wrists, but other bones can break as a result of low bone density.

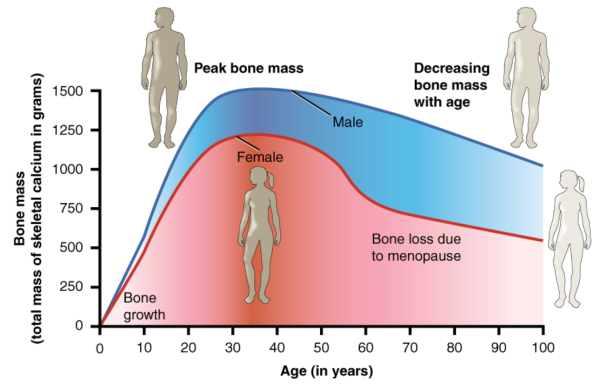

Osteoporosis can affect younger people, but it’s most common in women over 50 which is about when women go through menopause. This and the fact that men also lose bone mass, but at a later age then women, is shown in the image below.

Image credit: Anatomy & Physiology Conexxions via Wikimedia Commons(external link)

Bone is a living tissue and your body is always breaking down old bone and rebuilding new bone. You gain bone by building more than you lose.

- Bones contain the protein collagen and minerals, such as calcium and phosphorus, that make the collagen hard and dense.

- For healthy bone density (to keep your bones strong), your body needs enough calcium and other minerals and certain levels of hormones, including oestrogen in women and testosterone in men.

- Your body also needs vitamin D so you can absorb calcium from food and build it into your bones.

- Physical activity (especially weight-bearing exercise) also helps your bones become denser and stronger.

Your bones grow more and more dense until about the age of 30. After about the age of 40, your bone breaks down slightly faster than it’s replaced, and your bones slowly become less dense. If you lose too much bone, your bones become thinner (less dense) and weaker and are more like to break – this is osteoporosis.

Image credit: Depositphotos

Image credit: Depositphotos

Some loss of bone density is a natural part of getting older but other things can increase your risk whether you are male or female. Some of these you can do something about, but others may be linked to your medical history or genetic makeup.

Having a diet low in calcium and a lack of vitamin D

Having a low intake of calcium in your diet and not getting enough vitamin D (mainly from lack of sunlight or kidney disease) puts people of all ages at risk of low bone density and poor bone health.

Lack of exercise

People who are inactive are also at risk, as weight-bearing physical activity (such as walking, dancing or jogging) helps bone become denser.

Reduced hormone levels – oestrogen and testosterone

In women, the level of the hormone oestrogen decreases after menopause. Over many years, a low oestrogen level causes the inner part of your bones to become thinner, weaker and more brittle (breakable). Having irregular periods or early menopause (before 45 years old, often caused by having your ovaries removed) can also decrease oestrogen levels. In men, too little testosterone in conditions such as primary or secondary hypogonadism can also increase your risk of osteoporosis.

Being female

Women are at a greater risk of developing osteoporosis because of the rapid decline in oestrogen levels during menopause.

Getting older

Bones lose density as we get older and osteoporosis is more common in women over 65 years of age and men over 75.

Genetic factors

A family history of osteoporosis or fractures may mean you have inherited a tendency for lower bone density.

Some medical conditions

Medical conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, liver disease, coeliac disease, hyperthyroidism, and Cushing’s syndrome can contribute to thinning bones. Having an eating disorder may mean you’re not getting enough, or the right nutrients for maintaining strong bones.

Body weight

Being very thin and unable to put on weight can mean you’re more likely to break a bone if you fall as your bones are not as well cushioned. Your risk of osteoporosis is greater, probably due to general activity being less weight-bearing than it is for people who weigh more.

Some medicines

The ongoing use of some medicines, including anticonvulsants or steroids such as prednisone, can lead to thinning of your bones.

Smoking

Smoking can affect your body’s ability to make new bone, and this applies to being surrounded by smoke even if you don’t smoke yourself. Smoking also reduces the blood flow needed for developing bone and limits how well your body can absorb calcium and vitamin D.

Alcohol

Drinking too much alcohol can cause bone loss and broken bones. Alcohol can make it harder for your body to use vitamin D properly. It may also affect bone formation and increase losses of calcium and magnesium from your body. Also, if you drink too much alcohol you may not be eating well and there’s also an increased risk of falling. People who have more than 2 drinks a day may have a higher risk of low bone density and fractures than non-drinkers.

Can young people get osteoporosis?

Younger people can also be affected by osteoporosis. Younger women with eating disorders such as anorexia or bulimia are at higher risk of developing osteoporosis, as are younger women who do so much exercise they stop having periods.

One of the challenges with osteoporosis is that there are no early warning symptoms or signs. You may not know you have osteoporosis until you have one of the following:

- A fracture of your wrist, hips, spine or other bones that happens more easily than it should, eg, after a slight bump or a simple fall. This type of fracture is also known as fragility fracture.

- Loss of height – the vertebrae (bones) of your spine weaken because of bone thinning and they compress and your spine curves.

- With more severe osteoporosis, fractures occur when you're doing routine things such as bending, lifting or just getting up from a chair. This happens because brittle bones have trouble supporting your body weight.

Ask your healthcare provider for an osteoporosis check if any of these have happened to you, especially if you're over 50 years of age.

Your healthcare provider can find out your risk of osteoporosis from your medical history and by asking you about your lifestyle. Physical signs that you may have weak or thinning bones include:

- previous fractures (often of your wrist, hip or spine)

- a loss of height or a stooping (forward-bending) posture

- a curved spine.

Your healthcare provider may suggest you have a bone density scan (also called a dual energy X-ray absorptiometry or DEXA scan). This is a safe, painless scan which checks the density of bone in your hips and lower spine. Read more about DEXA scans.

Blood tests may also be done to rule out specific causes, such as any medical conditions that can cause osteoporosis.

Treatment for osteoporosis is decided on a case-by-case basis and depends on the results of bone density scans and other factors such as your age, gender, medical history and how severe it is.

To help decide which treatment is suitable, you and your doctor may use a FRAX score or a Garvan score. This shows your risk of having a fracture due to osteoporosis in the next 10 years. Read more about osteoporosis tests.

Treatment most commonly involves lifestyle changes, such as exercise, and medicines (including bisphosphonates and menopausal hormone treatment) that aim to increase bone density and reduce the risk of bone fracture. Read more about osteoporosis medicines. If you have a medical condition that causes your bones to be weak, treatment of this condition is also needed.

Exercise for osteoporosis

If you’ve already been diagnosed with osteoporosis, you need to include physical activity into your daily life. Apart from strengthening your bones, exercise may relieve pain, make everyday tasks easier to carry out and help maintain or improve your posture. The 3 types of activities most often recommended for people with osteoporosis are:

- Strength-training exercises: These include the use of free weights, weight machines, resistance bands or water exercises to strengthen the muscles and bones in your arms and upper spine. Strength training can work directly on your bones to slow bone mineral loss.

- Weight-bearing aerobic activities: These involve doing aerobic exercise on your feet, with your bones supporting your weight. Examples include walking, dancing, low-impact aerobics and gardening. These types of exercise work directly on the bones in your legs, hips and lower spine to slow bone mineral loss.

- Flexibility exercises: These can help increase the mobility of your joints, another important part of overall fitness. Being able to bend, extend and rotate your joints helps you prevent muscle injury. Increased flexibility can also help improve your posture.

Ask your healthcare provider which of these exercises are suitable for you. The main thing is to find an activity that you enjoy and that works for you depending on any medical condition you might have.

Read about other lifestyle changes to prevent osteoporosis and take care of your bones below.

Medicines for osteoporosis

Medicines used for osteoporosis work by slowing or stopping bone loss or rebuilding bone. Read about the types of medicines used for treating osteoporosis and how they’re used.

Falls prevention

A fall at any age can be dangerous but falls become more common and far more likely to cause injury after the age of 55 years. If you have osteoporosis, you’re more likely to break a bone if you fall, and if you do it might take longer to recover.

Exercise helps maintain bone density and strengthens muscles in your legs, which helps you maintain your balance and prevents falls.

Learning how to prevent falls (eg, by exercising regularly, improving your balance, and removing hazards in your home) can help you avoid broken bones and the problems they can cause. Read more about falls and falls prevention.

Apps reviewed by Healthify

You may find it useful to look at some joint and bone health apps and physiotherapy and exercise apps.

Taking steps to keep your bones healthy and strong is the best way to prevent osteoporosis from developing.

Eat a diet rich in calcium and vitamin D

Most of your body’s calcium is found in your bones. Calcium combines with other minerals to form the hard crystals that give your bones their strength and structure. Bones act like a calcium bank. If you don’t have enough calcium in your diet to replace any that’s lost so that there’s enough in your blood, your body ‘withdraws’ calcium from your bone bank and ‘deposits’ it into your blood. If your body withdraws more calcium than it deposits over a long period, you slowly lose bone density (bone strength) and you may be at risk of developing osteoporosis. Vitamin D helps your intestines absorb calcium into your blood, which delivers it to your bones, muscles and other body tissues.

The best way to increase your calcium is to eat a balanced, nutritious diet. This is better than taking supplements. Aim to get your calcium from foods such as low-fat dairy products. A 250ml glass of regular milk contains about 300mg of calcium, and there are also higher calcium versions available. If you have at least 2 servings of dairy products a day, you’re probably getting enough calcium.

For non-dairy options, soy milk usually has added calcium – check the product label. Calcium is also found in other foods, eg, dark green leafy vegetables, almonds, sardines, salmon with bones and tofu. Read more about calcium.

The best source of vitamin D is sunlight. The building blocks of vitamin D are made in the skin when it is exposed to sunlight. Five to 10 minutes of sun exposure to your face, arms, and hands 4 to 6 times per week is enough.

Most healthy European New Zealand adults living independently don’t need vitamin D supplements. People at risk of vitamin D deficiency, and who might benefit from a vitamin D supplement, include:

- frail older people who don’t go outside a lot, eg, because they’re housebound or in residential care

- people who wear clothing covering their skin most of the time

- people who have a condition that means they don’t absorb as much vitamin D from their food, eg, Crohn’s disease or coeliac disease

- those with dark skin because the melanin pigment can make it harder to make vitamin D from the sun.

Read more about vitamin D and sensible sun exposure.

Exercise regularly

Exercise is an important way to protect your bones. It can help preserve the bone strength you have and it improves coordination and balance, which can prevent falls that can lead to fractures.

While some aerobic exercises such as swimming and cycling are great for your health, they're not very helpful for building bone density. The activities that really help build and strengthen bone are the weight-bearing kind, which force you to put weight on your muscles and bones. These include gardening, stair climbing, tennis, walking, weight lifting, tai chi, aerobics and dancing. These activities require your muscles to work against gravity. Read more about exercise.

Avoid smoking and limit alcohol intake

Smokers tend to lose bone faster than non-smokers Find out ways to stop smoking.

Similarly, drinking too much alcohol can cause bone loss and broken bones. Limit your alcohol intake to 0 to 2 drinks per day and have 2 or more alcohol-free days per week.

Read more about how to keep your bones healthy.

If osteoporosis isn’t diagnosed or treated, it can cause complications. These include:

- more fractures in the future

- chronic pain

- immobility (not being able to move around)

- loss of independence

- reduced quality of life

- the need for long-term nursing care

- increased risk of death.

If you get fractures easily, it's important to find out if osteoporosis is the underlying cause so you can get treated properly and avoid complications.

Live Stronger NZ(external link)

All about osteoporosis(external link) Osteoporosis NZ

Osteoporosis and you(external link) Osteoporosis NZ

Osteoporosis and fractures(external link) Osteoporosis NZ

Brochures

Note: Some resources are from overseas so some details may be different in New Zealand, eg, phone 111 for emergencies or, if it’s not an emergency, freephone Healthline 0800 611 116.

Bone health risk factor test(external link) Osteoporosis NZ

Stop at one – make your first break your last [PDF, 1.8 MB] International Osteoporosis Foundation

Osteoporosis and you(external link) Osteoporosis NZ

All about osteoporosis(external link) Osteoporosis NZ

Apps/tools

Bone health tests

Physiotherapy and exercise apps

Osteoporosis apps

Falls prevention apps

References

- Guidance on the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in NZ(external link) Osteoporosis N, 2017

- Osteoporosis resources for health professionals(external link) Osteoporosis NZ, 2020

- Osteoporosis(external link) Auckland Regional HealthPathways, NZ, update 2023

- Bisphosphonates – addressing the duration conundrum(external link) BPAC, NZ, 2019

- Reid IR, Bristow SM, Bolland MJ. Cardiovascular complications of calcium supplements(external link) J Cell Biochem. 2015 Apr;116(4):494–501

- How does smoking contribute to osteoporosis?(external link) Healthline, US, 2024

- Nutrition(external link) Osteoporosis NZ

Clinical resources

Guidance on the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in NZ(external link) Osteoporosis NZ

Clinical standards for fracture liaison services in NZ(external link) Osteoporosis NZ, 2021

Osteoporosis risk check(external link) International Osteoporosis Foundation

Osteoporosis pathway(external link) NICE Guidelines, UK

FRAX – fracture risk assessment tool(external link) World Health Organization

Prevention of osteoporosis(external link) BPAC, NZ, 2008

Continuing professional development

Videos

Osteoporosis – Prof. Ian Reid (parts 1(external link) and part 2(external link)) (27 minutes + 32 minutes = 59 minutes) Pharmac, NZ, 2018

Podcast

Osteoporosis update – Ian Reid(external link) Goodfellow Unit, 2017

Distinguished Professor Ian Reid talks about Osteoporosis New Zealand's guidance on diagnosing and managing osteoporosis in Aoterao New Zealand. He is a professor of medicine and endocrinology at the University of Auckland and an international expert and research award winner in osteoporosis.

Brochures

Osteoporosis NZ, 2017

![]()

Osteoporosis NZ, 2016

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust.

Reviewed by: Dr Art Nahill, Consultant General Physician and Clinical Educator.

Last reviewed: