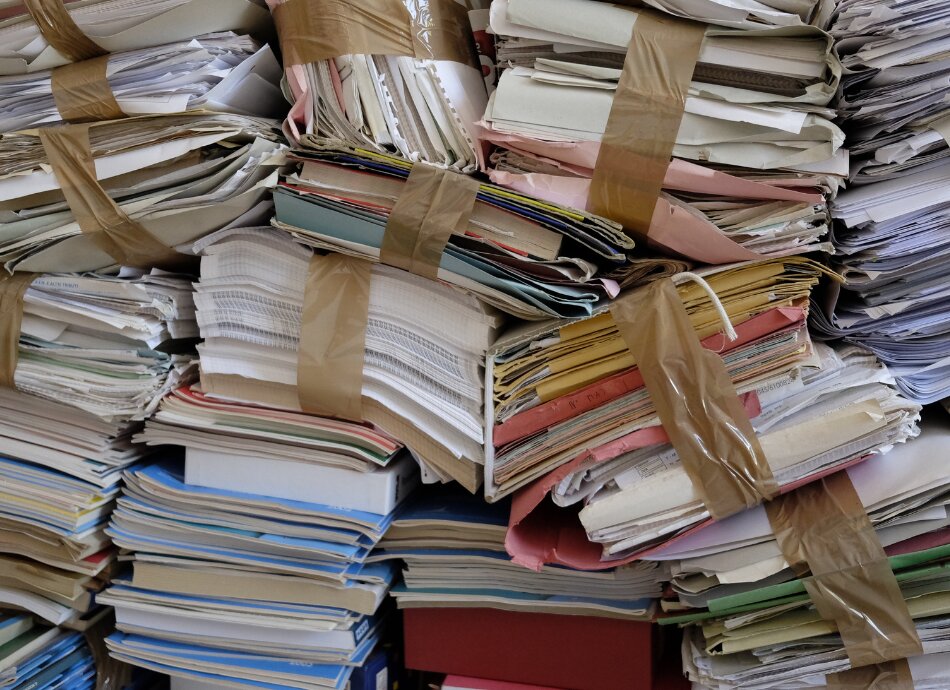

Hoarding is the term used to explain buying or getting a large number of objects or animals over time, resulting in excessive clutter. Your house getting messy and/or cluttered at times is not the same as hoarding disorder. Having hoarding disorder means your living spaces become so cluttered that they become unusable and/or unsafe.

VIDEO: What is hoarding?

The videos below explain what hoarding is and the difference between collecting and hoarding. This video may take a few moments to load.

(Peace of Mind Foundation, 2020)

Video: Difference between collecting and hoarding

This video may take a few moments to load.

(International OCD Foundation, 2018)

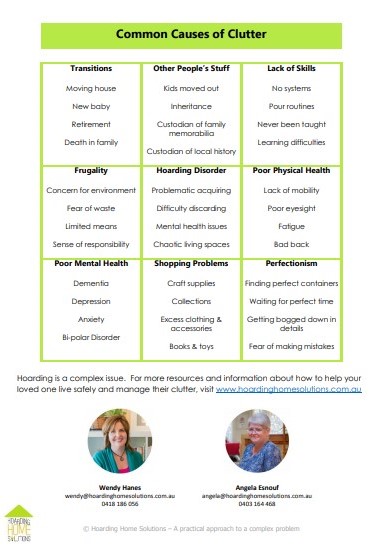

Hoarding disorder can be a condition by itself, as well as sometimes being a symptom of other mental health problems.

Hoarding can also be caused by some other conditions, eg, dementia or brain injury, which are generally diagnosed and treated differently to mental health problems. In these situations, the information in these pages might not apply. See our health topic pages on dementia and brain injury.