Symptoms of heart attack vary. However, if you have severe chest pain for more than 10 minutes, assume it's a heart attack.

Heart attack action plan

Minutes matter with a heart attack and early treatment can be life-saving. Make sure you have a heart attack action plan.

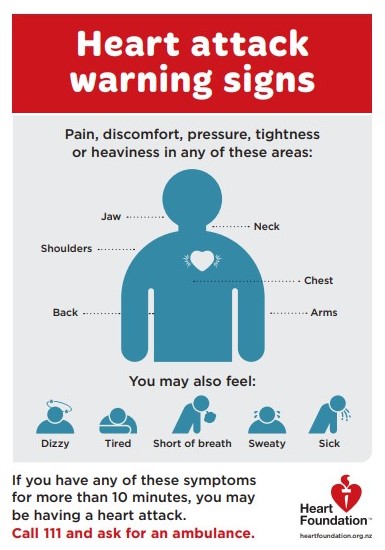

Know the warning signs

- Heavy pressure, tightness, crushing pain or unusual discomfort in the centre of your chest. This may stop or get less intense and then return. This symptom may not be the most noticeable symptom, especially in women.

- Pain spreading to your shoulders, neck, jaw and/or arms, and in some cases, through to your back.

- You may also sweat, have a sick feeling in your stomach, feel dizzy and be short of breath. These symptoms are the ones women most commonly notice.

If you have any of these symptoms for more than 10 minutes you may be having a heart attack. Don't delay, call 111 for an ambulance.

Take action immediately

- Call 111, ask for the ambulance service and tell them you're having a possible heart attack.

- If available, chew 1 aspirin, unless you have been previously advised not to take aspirin.

- Rest quietly and wait for the ambulance.

- Get someone to wait with you, if possible.

- Remaining calm means you are less likely to suffer some of the heartbeat disturbances that create problems for you and your immediate medical advisors.

Get it checked out

People often don't know what's wrong and wait too long before getting help. The warning signs of a heart attack vary and it's possible to have no pain (especially if you are a woman or have diabetes) or the only sign may be indigestion-type pain (heartburn).

Even if you're not sure it's a heart attack, have it checked out.

- Fast action can save lives

- Calling 111 is almost always the fastest way to get life-saving treatment. Emergency medical services staff can begin treatment when they arrive.

- Don't travel by car if there is a possibility of a heart attack occurring.