If you have prostate cancer, you will be referred to a specialist (urologist) and then possibly a radiation oncology specialist. The choice of treatment depends on the size, type, growth and spread of the cancer, and your age, general health, symptoms and ultimately your informed, personal choice.

Treatment options for prostate cancer include active surveillance, surgery, radiation therapy (radiotherapy), hormone therapy and palliative care.

Most people want to know whether their cancer can be successfully treated. The outcome of the treatment will depend on the type of cancer and whether it has spread, how quickly it grows, and how well the treatment works. If the prostate cancer is localised to the prostate gland, it's sometimes slow growing and may never need treatment. Other localised prostate cancers do require treatment and often it's possible to successfully get rid of the cancer. If the cancer has spread outside of the prostate gland, treatments can often keep it under control for many years.

Prostate cancer classification

Prostate cancer is classified by the Gleason Score. A Prostate Cancer Gleason Score helps to determine how aggressively the prostate cancer is likely to behave and how quickly it's likely to grow. The score is also an indicator of how likely it is to spread beyond the prostate gland. The Prostate Cancer Gleason Score score ranges from 2 to 10. To determine the Gleason score, the pathologist uses a microscope to look at the patterns of cells in the prostate tissue. The cell pattern is given a grade of 1 (most like normal cells) to 5 (most abnormal). If there is a second most common cell pattern, the pathologist gives that pattern a grade of 1 to 5 as well. The pathologist adds the 2 most common grades together to make the Gleason score. If only 1 pattern is seen, the score for that pattern is used twice (eg, 5 + 5 = 10). A high Gleason score (such as 10) means a high-grade prostate tumour. High-grade tumours are more likely than low-grade tumours to grow quickly and spread.

The International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) grading system uses the Gleason score to further grade the cancer. The lower the grade the less likely the cancer is going to spread. The grade helps your specialist to plan your treatment:

- Grade group 1: Gleason score 6 or lower (low-grade cancer)

- Grade group 2: Gleason score 3 + 4 = 7 (medium-grade cancer)

- Grade group 3: Gleason score 4 + 3 = 7 (medium-grade cancer)

- Grade group 4: Gleason score 8 (high-grade cancer)

- Grade group 5: Gleason score 9 to 10 (high-grade cancer)

Prostate cancer management

Management options for prostate cancer include active surveillance (watch closely and regularly), or treatment such as surgery, radiation therapy (radiotherapy), hormone therapy or chemotherapy.

Active surveillance (no active treatment, but watch and wait)

No treatment is provided and instead, you are monitored regularly with blood tests or other investigations (eg, scans and biopsies), either in hospital or by healthcare provider follow-ups. This option is usually recommended if you have an early stage of prostate cancer or your cancer is slow growing. This is because it may not be of benefit to have treatment if the cancer isn't affecting your quality of life – and it may never do so. Active surveillance can also be offered if you have a late stage of prostate cancer and the management of other health conditions is more important.

Surgery

This can be an option if it's possible to remove all the cancer cells by taking out part or all your prostate. The aim of surgery is to cure your prostate cancer. As with any type of surgery there are risks. With prostate cancer surgery risks include bleeding, infection, scar formations (stricture), incontinence (unable to control urine) or impotence (unable to get or maintain an erection)

Radiation therapy (radiotherapy)

The aim of radiotherapy is also to cure your prostate cancer. Radiotherapy has side effects such as pain when peeing, loose bowel motions, bleeding from your rectum, impotence and more. Your healthcare team will explain more to you when discussing treatment options. Read more about radiotherapy.

Hormone therapy

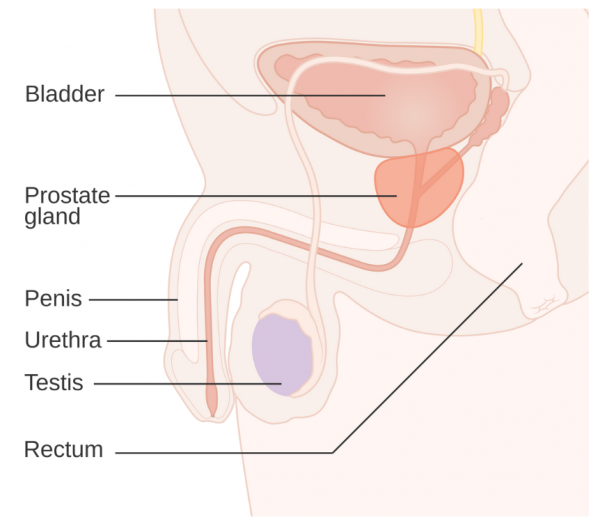

Testosterone helps prostate cancer cells grow. Hormone therapy involves giving you medicines to stop your testicles from producing the male hormone testosterone. These medicines are called luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) analogues (eg, goserelin). Another name for these medicines is gonadotropin-releasing hormone anologs. Other medicines that stop testosterone from acting on cancer cells are known as anti-androgens (eg, bicalutamide, cyproterone) and they're often used together with LHRH analogues.

Palliative care

This is usually offered to people with later-stage or advanced cancer. Treatment is focused on relieving your symptoms. Read more about palliative care.