If you're a frequent visitor to Healthify, why not share our site with a friend? Don't forget you can also browse Healthify without using your phone data.

Hepatitis A

Key points about hepatitis A

- Hepatitis A is an infection caused by the hepatitis A virus. The virus causes inflammation of your liver.

- It's usually spread through contact with an infected person's faeces (poo).

- The virus is often spread by poor hand-washing before preparing kai.

- Symptoms are usually mild, and the infection goes away after several weeks.

- There's no treatment but you can stop it from spreading to others through careful hand washing and avoiding preparing food for others for at least a week.

- There’s a safe and effective vaccine to prevent hepatitis A.

Hepatitis A is a viral infection that causes inflammation of your liver. It’s caused by the hepatitis A virus (HAV) and is usually spread through contact with an infected person's faeces (poo). This may happen from eating contaminated food, or through close contact with an infected person.

Hepatitis A is uncommon in Aotearoa New Zealand. Most people who have hepatitis A have recently travelled overseas.

Symptoms include flu-like symptoms and yellowing of your skin and the whites of your eyes (this is called jaundice). Some people have no symptoms at all, and serious problems are very rare. Symptoms usually last for several weeks. Less commonly, the symptoms can come and go for up to 6 months.

There’s no particular treatment for hepatitis A infection. Usually, your immune system will fight the virus and your liver will heal.

The hepatitis A virus is carried in the faeces (poo) of an infected person. You can come into contact with the virus when you:

- drink contaminated water

- eat food prepared by someone with hepatitis A virus who didn't wash their hands well after going to the toilet

- have sexual contact with someone with the virus

- don't wash your hands after going to the toilet.

Hepatitis A is very contagious (easily spread) and people can spread the virus before they feel sick. Only a small amount of virus is needed to spread the infection. The virus can survive on objects and in water for months.

Hepatitis A is also occasionally spread by injected drug use.

Hepatitis A is rare in Aotearoa New Zealand, but it can affect anyone who isn’t immune to the disease – that is, anyone who hasn’t been vaccinated against hepatitis A or who hasn’t already had hepatitis A. You are at higher risk of getting the infection if you:

- travel overseas, especially to countries where sanitation is not good

- go to or work in a day-care centre

- have a job that exposes you to faeces (poo), such as healthcare workers and people who work with sewage

- work in the sex industry

- are a man and have sex with men

- inject illegal drugs

- live with a person who has hepatitis A and share personal things such as toothbrushes, facecloths, towels, etc.

If you’re travelling overseas ask your healthcare provider whether you need hepatitis A vaccination before you leave. Also, find out whether it’s safe to drink the tap water and take extra care with everything you eat and drink.

When travelling in countries where the local water may be contaminated:

- avoid foods you can't peel or cook

- don’t drink unpackaged drinks or ice

- don’t eat shellfish.

Image credit: Canva

Hepatitis A can cause temporary swelling of your liver, but it doesn’t usually cause lasting damage. It usually gets better on its own after several weeks.

Infants and children usually don’t have any symptoms. The older you are, the more severe the symptoms of hepatitis A tend to be, and the illness can be more serious in people with chronic liver disease or those who are immunocompromised (that is, people who have a weakened immune system).

Symptoms of hepatitis A

- tummy pain

- nausea (feeling sick)

- vomiting (being sick)

- diarrhoea (runny poo)

- fever

- not wanting to eat

- flu-like symptoms (without cough or runny nose)

- yellowing of your skin and eyes (jaundice)

- pale-coloured faeces (poo)

- feeling very tired

- dark, reddish-brown urine (pee).

Symptoms can appear from 2 to 7 weeks after you’ve come into contact with the hepatitis A virus and usually only last 1 to 2 weeks. Sometimes, in more severe cases, it can last weeks to months. In very rare cases, it can be life threatening.

Symptoms can appear from 2 to 7 weeks after you’ve come into contact with the hepatitis A virus and usually last for several weeks but less than 2 months. For some people, symptoms last or come and go for up to 6 months.

You are infectious (that is, you can pass the infection on to someone else) for 2 weeks before you show any symptoms and for 1 week after you develop jaundice (yellowing of your skin and eyes).

To reduce the risk of other people getting infected, stay home and don't prepare food for other people for 7 days from when jaundice first appeared. After you’ve recovered from hepatitis A, you’re immune and can’t get it again.

To diagnose hepatitis A infection, your healthcare provider:

- will ask you about your symptoms and travel history and check your immunisation record

- will look for noticeable physical signs such as jaundice (yellowing of your skin and eyes)

- may also ask for blood tests, such as liver function tests and hepatitis A antibody tests.

Usually, no particular treatment is needed if you have hepatitis A. In most cases, your immune system will fight the virus and your liver will heal completely. You may be prescribed medicines to help relieve your symptoms.

It's very rare to become very sick and need to be cared for in hospital.

To help your recovery from hepatitis A:

- rest – hepatitis A infection can make you tired, so rest when you feel you need to

- keep up your fluid intake to replace fluid lost from diarrhoea and vomiting

- protect your liver – avoid alcohol and review your medicines with your doctor or nurse prescriber as some medicines can cause liver damage

- avoid unnecessary medicines that might damage your liver, eg, paracetamol.

To reduce the risk of spreading hepatitis A to others:

- practice good hand hygiene using soap and water

- stay home and don’t prepare food for other people for 7 days from when jaundice first appeared

- use hot water and detergent to wash bed-linen, underpants, towels and handkerchiefs

- don’t share personal items such as toothbrushes, towels and face cloths.

Most people with hepatitis A recover completely, but in very rare cases it can cause liver failure or death.

Sometimes a person who just recovered from hepatitis A will get sick again, however, this is normally followed by full recovery.

The risk of serious liver problems from hepatitis A infection is greater if you're an older person, if you already have liver disease, or if you have decreased immunity to disease.

Unlike chronic chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C, hepatitis A virus doesn’t cause chronic liver disease.

Practice good hand hygiene

Good hand hygiene is the best way to prevent hepatitis A. Avoid the spread of germs by:

- washing hands before and after preparing food

- washing hands before eating

- washing hands after going to the toilet or changing a baby’s nappy.

Read more about hand hygiene using soap and water.

Take care with what you eat and drink

- Boil your drinking water if it comes from an untreated source, such as a river.

- High temperatures, such as boiling or cooking food or liquids for at least 1 minute at 85°C, kill the virus but freezing temperatures don't.

Protect your body from infection

- Don’t share personal items such as toothbrushes or injecting equipment such as needles.

- Practice safe sex by using condoms.

Get vaccinated if you're at high risk

There's a vaccine that protects against hepatitis A infection. To get the full benefit of the hepatitis A vaccine, 2 doses of the vaccine are needed.

- After 1 dose of hepatitis A vaccine, protection from hepatitis A lasts for at least 1 year.

- A second booster dose, given 6 to 12 months after the first dose, gives longer term protection. It's predicted that protection could last for 20 years.

The vaccine is free for people at risk of severe infection, including:

- people who’ve had an organ transplant

- children with chronic liver disease

- people who live in close contact with someone with hepatitis A infection.

Vaccination is recommended but not free for other groups including:

- adults with chronic liver disease, including chronic hepatitis B or chronic hepatitis C

- men who have sex with men

- some occupational groups, eg, healthcare workers exposed to faeces/poos, employees of early childhood services (especially where there are children too young to be toilet trained), plumbers, sewage workers, those who work with non-human primates (eg, at zoos)

- food handlers during community outbreaks of hepatitis A

- military personnel who are likely to be sent to high-risk areas

- injecting drug users.

If you’re planning to travel internationally, you may be at risk of hepatitis A infection and should consider getting vaccinated. The vaccine should be given at least 2 weeks before you leave so your body has time to respond to the vaccine.

- High-risk areas include Africa, Asia, Central and South America and the Middle East.

- Moderate-risk areas include the Mediterranean, Eastern Europe (including Russia) and parts of the Pacific.

Read more about the hepatitis A vaccine.

Hepatitis A(external link) Hepatitis Foundation NZ

Hepatitis A(external link) The Immunisation Advisory Centre, NZ

Hepatitis A(external link) Healthy Sex, NZ

Brochures

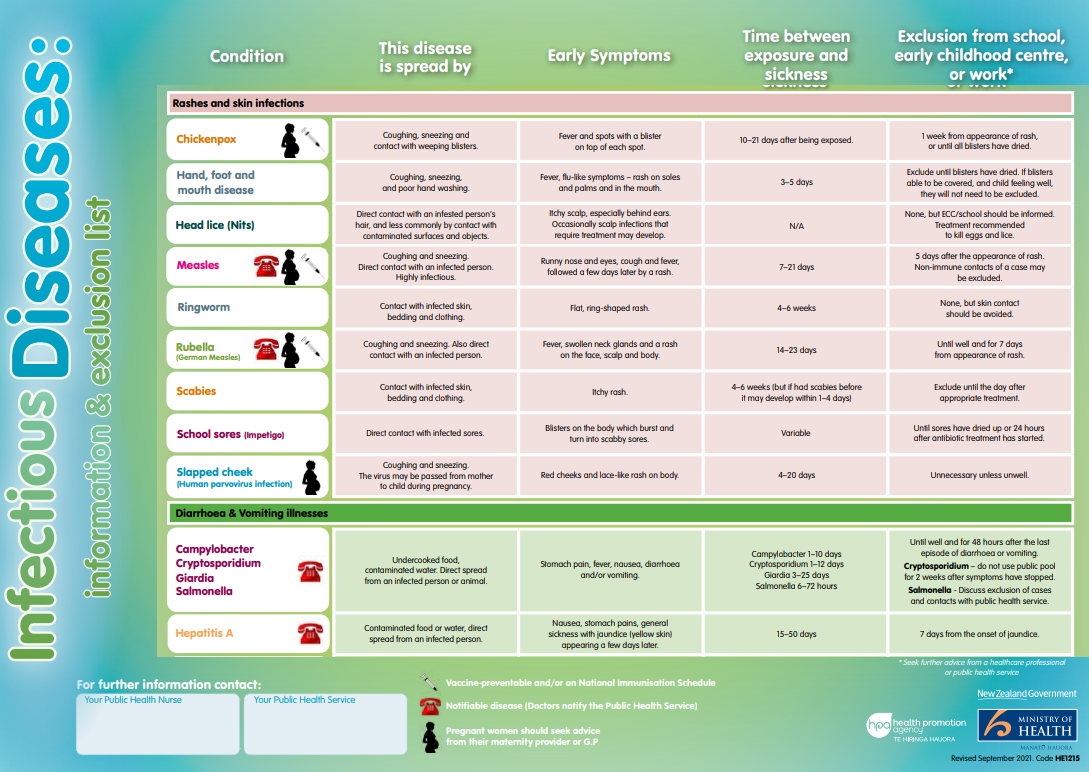

Infectious diseases(external link) HealthEd, NZ, 2023

Fact sheet – hepatitis A(external link) HealthEd, NZ Available in the following languages: Tongan(external link), Samoan(external link)

References

- Hepatitis A(external link) Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora

- Hepatitis A(external link) Hepatitis Foundation, NZ

- Hepatitis A(external link) Immunisation Handbook, NZ

- Hepatitis A(external link) The Immunisation Advisory Centre, NZ, 2017

- Havrix(external link) The Immunisation Advisory Centre, NZ, 2019

- Hepatitis A vaccines(external link) NZ Formulary

- Hepatitis A(external link) World Health Organization, 2023

Hepatitis A(external link) Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora

Brochures

Health Ed and Ministry of Health, NZ, 2022

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust.

Reviewed by: Dr Sharon Leitch, GP and Senior Lecturer, University of Otago

Last reviewed: