Heart valve disease | Mate manawa takirere

Key points about heart valve disease

- There are 2 main types of heart valve problems with a variety of causes and treatments.

- One is valvular stenosis (narrowing of the valve opening which limits the flow of blood).

- The other is valvular insufficiency (also called regurgitation or incompetence) when the valve is leaky and back-flow of blood occurs.

- Most valve problems can be treated using medicines or by surgery.

- Your treatment will depend on the cause of your problem and the effect it's having on your heart.

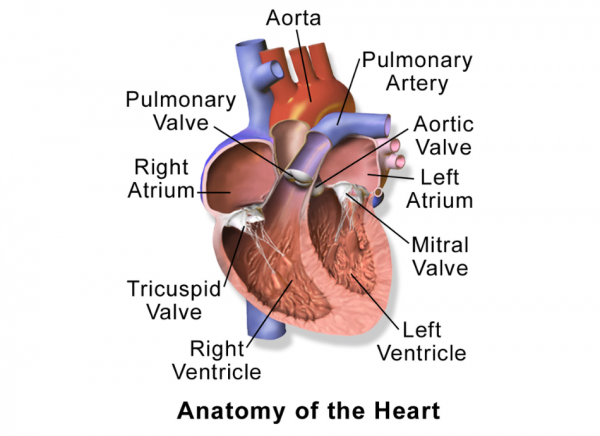

Your heart has a left and a right side and each side has an upper and a lower chamber (an atrium and a ventricle). There are 4 valves in the heart, 1 between each atrium and ventricle and 1 at the exit of each ventricle. The valves make sure that blood flows in 1 direction through the heart like a one-way traffic system. They open and close at particular times during the normal beat of the heart. They open to let the blood through at the right time and then close to stop the blood flowing backwards.

The image below shows the 4 chambers of the heart and the location of the 4 valves.

Image credit: Bruce Blausen Wikimedia Commons

Video: British Heart Foundation - How does a healthy heart work?

This video shows how the blood flows through the heart. It may take a few moments to load.

(British Heart Foundation, UK, 2014)

If your heart valves become diseased or damaged, they may not fully open or close. This can disrupt the flow of blood through your heart either by:

- narrowing the space the blood can flow through – this is known as valvular stenosis, or

- allowing the blood to leak back into the chamber it’s come from – this is called valvular regurgitation or insufficiency.

You may have one or both of these valve problems.

The main causes of heart valve disease are:

- being born with an abnormal valve or valves (congenital heart disease)

- having had rheumatic fever (rheumatic heart disease) after a bout of strep throat

- cardiomyopathy (disease of the heart muscle making it become enlarged, thick or rigid)

- damage to the heart from heart disease or an infection known as endocarditis

- getting older.

You may not have any symptoms, or may have several, depending on how badly the valve is working.

Common signs and symptoms include:

- a heart murmur (whooshing sound when somebody listens to your heart with a stethoscope)

- shortness of breath or feeling breathless

- swollen ankles and feet and sometimes tummy (abdomen)

- palpitations (a fluttering or pounding feeling in your chest)

- chest pain

- feeling light-headed, weak or dizzy

- unusual tiredness.

If you’re having any of these symptoms talk to your healthcare provider.

Your healthcare provider will start by talking to you about your symptoms and listening to your chest with a stethoscope. If they think you have problems with a heart valve, there are tests they can arrange for you to see how your heart is working.

These include:

- electrocardiogram (ECG) which maps the electrical activity of the heart

- echocardiogram (echo) or ultrasound of the heart

- chest X-ray

- coronary angiography (cardiac catheterisation) which looks at blood flow to the heart.

Your treatment will depend on:

- which valve is affected

- how many valves are affected

- how badly it’s affected

- The condition of your heart muscle

- your symptoms and overall health.

You may not need any treatment, apart from regular check-ups.

If you do need treatment, it could involve taking cardiovascular medicines or having surgery to widen a narrowed valve opening or to repair or replace a damaged valve (see below).

Valve surgery

If your healthcare team decide that your symptoms and quality of life could be improved by having surgery, there are 2 types.

- A valve repair is often done if a valve is leaking but isn’t seriously damaged.

- A valve replacement is done when the old valve is too damaged to repair and needs to be replaced with a new one. The replacement can be a mechanical (artificial) valve or a valve from another person or animal.

Your surgeon will discuss the options with you and help you decide what to have done.

Whether or not you have treatment or surgery for your heart valve disease, there may be things you can do to improve your health and lifestyle. These include:

- having a heart healthy diet

- maintaining a healthy body weight

- quitting smoking

- doing at least 30 minutes of exercise a day

- managing your stress

- looking after your teeth – any disease or gum abscess should be treated promptly, to lower the risk of bacteria getting into the bloodstream and possibly damaging the heart valves or endocardium (tissue that lines the inside of the heart chambers).

You may need to take a course of antibiotics when you’re having dental procedures or some medical procedures. Your healthcare provider or dentist can advise you on this.

Apps reviewed by Healthify

You may find it useful to look at some Quit smoking apps, Nutrition, exercise and weight management apps and Self-management apps.

Heart support groups and services in NZ(external link) Heart Foundation NZ

Emotional and social support(external link) Heart Failure Matters, European Society of Cardiology

Heart valve disease(external link) Heart Foundation NZ

Heart valve surgery(external link) Heart Foundation NZ

Mitral valve problems(external link) NHS Choices

Heart valves – explained(external link) Watch, learn, live – interactive cardiovascular library – American Heart Association

Brochures

Living well after a heart attack(external link) Heart Foundation of NZ, 2020

Staying well with heart valve disease(external link) Heart Foundation, NZ, 2020

Apps/tools

Heart age forecast(external link)

Stroke apps

Quit smoking apps

Nutrition, exercise and weight management apps

Self-management apps

References

How a healthy heart works(external link) British Heart Foundation, UK, 2021

Heart valve disease(external link) British Heart Foundation, UK, 2021

What is heart valve disease?(external link) Heart Foundation NZ

Current guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease(external link) American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association, US, 2020

European guidelines for the management of valvular disease(external link) European Society of Cardiology; European Association of Cardiothoracic Surgeons, 2021

Also see our page on Heart failure for healthcare providers

Brochures

Heart Foundation of NZ, 2020

Heart Foundation, NZ, 2020

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust.

Reviewed by: Dr Art Nahill, Consultant General Physician and Clinical Educator

Last reviewed: