- Gender identity refers to an innate sense of who you are. This may be the same as or different from the sex that was assigned to you at birth. How you choose to express your gender identity varies from person to person.

- Gender dysphoria is a term used to describe uncomfortable or distressing feelings that some people experience because the sex they were assigned at birth does not match their gender.

- If you are transgender, or experience gender dysphoria, you may want to take steps to be recognised as your gender, rather than the sex you were assigned at birth. These steps may include changing your name, wearing clothes that affirm your gender, taking hormones, or having surgeries.

- Sexual orientation is different to gender. It refers to who you are attracted to and may be described as heterosexual/straight, lesbian, gay, bisexual, pansexual, asexual, takatāpui, or using other terms.

- Gender diversity is a term to cover the range of possible gender identities, such as female, male, transgender, intersex, non-binary and takatāpui.

- If you are unsure about your gender, or your child is unsure about theirs, there is support available to help you

Low or no data? Visit Zero Data then search for 'Healthify'. Click on our logo to return to our site and browse for free.

Gender dysphoria

Key points about gender dysphoria

- When you are born, you are assigned a sex – male, female or indeterminate – depending on the appearance of your external genitalia.

- You may feel that the sex you were assigned is correct. This is called being 'cisgender'.

- You may feel that the sex you were assigned is incorrect. This is called being 'transgender'.

- This incongruence can be distressing, and the experience of distress is known as ’gender dysphoria'.

- If you experience gender dysphoria you may want make changes, eg, changing your name, wearing clothes that support your gender, taking hormones or having surgeries.

- Support is available.

Gender dysphoria refers to the distress, anxiety or uncomfortable feelings some people experience due to being assigned a sex and gender that doesn’t match their own experience of themselves. Medical treatment to alleviate this distress is available for those who need it.

Signs of gender dysphoria can appear at a young age. For example, a child may refuse to wear typical boys’ or girls’ clothes, or dislike taking part in typical boys’ or girls’ games and activities. Note that these behaviours are often a normal part of childhood development, but if they are persistent and consistent, it may be more than “just a stage”.

People with gender dysphoria can feel that their body doesn’t match their gender. They may have a strong desire to change, alter or remove physical signs of the sex they were assigned, such as facial hair or breasts. These feelings often become more intense during puberty, when the physical signs are changing most rapidly and are most outwardly apparent.

People with gender dysphoria may also experience distress about how they will be treated if they tell people close to them about their gender and may be concerned about the discrimination they may face if they do take steps to affirm their gender.

Apps reviewed by Healthify

You may find it useful to look at some Sexuality and relationship apps.

Gender development is complex. There are many possible reasons why a person’s assigned sex differs from their gender, including factors related to physiology, the environment, and their personal experiences. Many transgender people don’t experience any distress related to their gender identity at all, whilst for others it can be really impacting.

Babies can also be born as intersex. 'Intersex' is an umbrella term that refers to people born with one or more of a range of variations in sex characteristics that fall outside of traditional conceptions of male or female bodies. For example, intersex people may have variations in their chromosomes, genitals or internal organs like testes or ovaries. If a person has an intersex condition, they may be cisgender (agreeing with the sex they were assigned at birth) or transgender (not agreeing with the sex they were assigned at birth), or they may simply identify both their sex and gender as intersex. It is important to not make assumptions about this, but instead to let people define their own experiences.

When an intersex infant is born with ambiguous genitalia, they have historically been assigned as 'male' or 'female'’, and had surgeries performed to conform them to this assignment. However, this is not ethical practice. Intersex infants should never be operated on and should only receive surgeries if they elect to later in life.

The distress, uncomfortable feeling and/or anxiety associated with gender dysphoria may need to be treated. An assessment by a health professional will determine whether you have distress associated with gender dysphoria and will help clarify what your needs are (which are entirely individual and may change with time). The person talking with you (eg, a doctor or counsellor) will want to know:

- whether there's a clear difference between your assigned sex and your gender

- whether you have a strong desire to change your physical characteristics as a result of your gender dysphoria

- how you're coping with any difficulties you’re experiencing

- how your feelings and behaviours have developed over time

- what support you have, such as friends, family, support groups and your community.

The assessment may also involve a more general assessment of your physical and psychological health.

Note: A doctor does not need to examine your genitals as part of this assessment. If they request a genital exam for any reason, they must discuss the reason with you, and ask for your consent or permission. You have the right to say no to this and to have your decision respected. You also have the right to have a support person or someone in the room with you during any examination. The doctor must record the medical purpose and result of the examination. Checking for general changes is not a medical reason and you can walk out of any appointment if you feel that you are being treated inappropriately.

Once your doctor or counsellor has talked with you, they will discuss with you what your goals are. The main aim of any treatment is to affirm your gender, support you and reduce the distress you are feeling, but you may have other goals as well.

Some people experiencing gender dysphoria may choose to 'transition'. Transitioning is a process that someone can choose to go through that aims to transition them from being seen as the sex they were assigned at birth to their innate or ‘affirmed’ gender. For many transgender people, transitioning eliminates or greatly reduces gender dysphoria.

Transitioning can include:

- ‘coming out’ to friends, family and others as transgender or as your innate or affirmed gender

- dressing and living in a way that expresses your innate or affirmed gender

- changing your name

- asking people to use different pronouns to describe you (for example he, she or they)

- having your gender changed on legal identification documents such as your birth certificate, passport or driver's licence

- taking puberty blockers – medication to delay physical changes associated with puberty

- taking hormones (oestrogen or testosterone)

- having surgeries to change your body

- having counselling to reduce distress, anxiety or other distressing feelings

- connecting with transgender community to build relationships, resilience and support

- connecting your family or friends with support, to help them understand and adjust.

Psychological support

Gender dysphoria can cause a significant amount of distress, so counselling or psychotherapy can be really helpful. As a demographic or population, transgender people experience higher rates of mental health conditions due to elevated levels of stigma against them, and high rates of discrimination in education, housing, healthcare, employment, access to goods and services, participation in public social life and input into policy and legislative decisions that affect their lives.

Mental health conditions may include depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, alcohol or other drug use, or eating disorders. Counselling or psychotherapy can give you an opportunity to discuss your transition, your support system (including whānau and friends), and your treatment options, and ensure this is done as safely and comfortably as possible for you.

Gender-affirming hormone therapies (hormone replacement therapy or HRT)

Gender-affirming hormone therapy creates a testosterone or oestrogen-dominated endocrine system (depending on what you want). It affects the appearance of secondary sex characteristics such as fat distribution, breast growth, deepening of your voice and hair growth.

Service providers who can assist you to access hormone therapy include:

- primary healthcare teams, such as your GP

- sexual health services

- youth health services

- hospital services, including paediatrics (child and youth health specialists) and endocrinologists (hormone specialists)

- community health services, including in-community clinics and health promotion services.

Availability and access to these services varies depending where in New Zealand you are located. Some of the national organisations listed on the support page will be able to help you find the most appropriate place nearest to you.

Note that prescribing of some medications such as cyproterone and testosterone is restricted in New Zealand and may require specialist sign off.

The process of starting hormonal therapy includes assessing your readiness from a medical and psychosocial perspective. This is to ascertain that you know what to expect from your hormones (both good and bad) before you start, and that you have all the information and support you need to make a considered decision.

Gender-affirming surgeries

Gender-affirming surgeries include:

- feminising breast augmentation for trans women

- masculinising chest reconstruction for trans men

- hysterectomy (removal of the uterus)

- salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of ovaries and fallopian tubes)

- orchidectomy (removal of testicles)

- facial feminisation

- laryngeal shave (reducing the size of the Adam’s apple)

- masculinising and feminising gender affirming genital surgery.

Availability of these surgeries (except for genital surgery) will depend upon the surgical expertise and capacity within your district health board (DHB) and the clinical priority given to your surgery.

Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora has funded a limited number of gender affirming genital surgery since 2005, through its High Cost Treatment Pool. Surgeries have been provided in the private sector in New Zealand or overseas. There is currently a long waiting list for the surgery.

If you wish to access this surgery, discuss this with your DHB specialist. If you are not currently under the care of a specialist, then discuss this with your GP, who can make a referral to an appropriate specialist.

Voice therapy

Voice therapy can help you train your voice to achieve a pitch and communication style that feels right for you. Ask your doctor if there is any funded voice therapy option in your region, or talk with one of the support organisations listed below about seeking funding through Work and Income NZ.

Are there any risks or problems associated with surgery or hormone therapy?

Most people are happy with the results. A recent review of 27 studies was carried out by Bustos and colleagues. They found a less than 1% regret rate following gender-affirming surgery.

However, as with any medication or surgical procedure, there can be problems. All operations can have complications and hormone treatment also comes with some risks. Hormone therapy may produce complex changes that you'll need to consider, including changes to your fertility and sexuality. You may want to investigate or talk to your doctor about fertility preservation (like freezing sperm or eggs) before you start hormone treatment.

Hormone therapy can also cause other health problems including:

- blood clots

- abnormal cholesterol levels

- high blood pressure

- type 2 diabetes

- cardiovascular disease

- stroke.

It’s important to discuss these with your specialist so you can make informed decisions, taking into account the risks and the benefits. It can also help to speak with others who have experienced gender dysphoria – they will be able to tell you what it was like from a personal perspective. Find out where a local support group is, or contact one of the national support agencies listed below.

Gender Minorities Aotearoa(external link) Gender Minorities Aotearoa is a cross-cultural, transgender-led organisation that operates on a kaupapa Māori public health framework. Its activities include research, providing information and resources, advocacy, education and training, operating services for gender minorities and providing support for takataapui, transgender and intersex people, and referrals to other services.

Transgender and Intersex NZ(external link) The Facebook group is the largest online transgender community support group with a New Zealand-based membership. This group is primarily for sharing information between people of diverse genders and sex characteristics, and has a secondary focus on supporting parents and whānau as well as those who work with trans people and supportive others.

Hauora tahine – pathways to transgender healthcare(external link) Secondary services that provide gender-affirming healthcare for transgender and gender diverse people across the Northern Region DHBS (Northland, Waitemata, Auckland and Counties Manukau).

Intersex Youth Aotearoa (IYA)(external link) Intersex Youth Aotearoa is a place for all people with intersex variations/DSD, and their whānau and friends to share information, find support and network with each other.

New Zealand Parents and Guardians of Transgender and Gender Diverse Children (NZPOTC)(external link) is a parent-led group where you can find the information, guidance, advice and companionship to help you and your family/whānau safely and happily navigate your journey, knowing you are never alone.

Naming NZ(external link) An organisation to help transgender, gender diverse and intersex youth with updating identity documents to correctly reflect their sex and gender.

A printable card(external link) to help transgender people with communicating their preferred names and pronouns.

For a full list of national and local support groups, see gender diversity support organisations

The following links provide further information about gender diversity. Be aware that websites from other countries may have information that differs from New Zealand recommendations.

Gender identity(external link) Common Ground, NZ

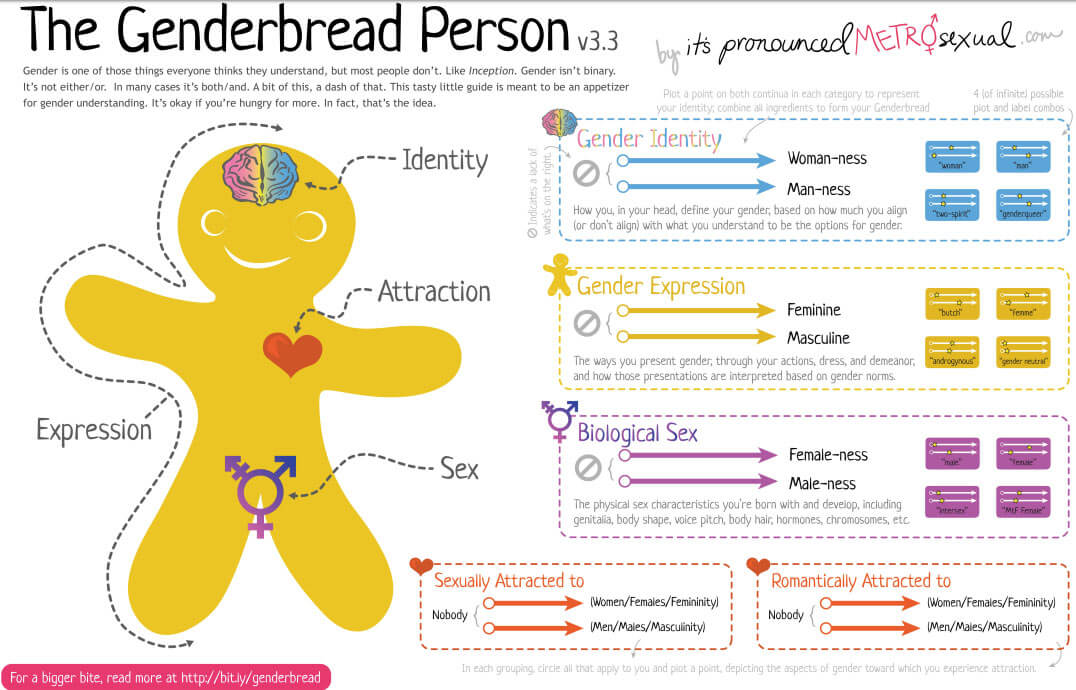

Breaking through the binary – gender explained using continuums(external link) itspronouncedmetersexual.com

Find information and services(external link) Gender Minorities Aotearoa

Hormone replacement therapy(external link) Transgender NZ Issue 1, Gender Minorities Aotearoa, 2017

Wellbeing and mental health among rainbow New Zealanders(external link) HPA, NZ

Let's talk – a resource guide for parents(external link) Outline, NZ

Counting ourselves survey report(external link) Counting Ourselves, NZ

Trans and non-binary inclusive workplaces – a guide for employers and employees(external link) Outline, NZ

For parents

Let's talk – a resource guide for parents(external link) Outline, NZ

Supportive vs. Rejecting Parenting(external link) Gender Spectrum, US, 2017

Help! Is my child transgender?(external link) Gender Minorities Aotearoa

Apps

Sexuality and relationship apps

Resources

Note: Some resources are from overseas so some details may be different in New Zealand, eg, phone 111 for emergencies or, if it’s not an emergency, freephone Healthline 0800 611 116.

Takatapui – part of the whanau(external link) Tīwhanawhana Trust and Mental Health Foundation, NZ, 2021

Accessing gender-affirming care in Aotearoa(external link) RainbowYOUTH, NZ, 2019

Takatāpui – part of the whānau (external link)Tīwhanawhana Trust and Mental Health Foundation, NZ, 2015

Families in transition – a resource guide for families of transgender youth(external link) Central Toronto Youth Services, Canada, 2008

Trans 101 glossary of trans words and how to use them(external link) Gender Minorities Aotearoa, 2020

To be who I am(external link) Human Rights Commission, NZ, 2007

Handbook for parents – consortium on the management of disorders of sex development(external link) Intersex Society of North America, 2006

Making schools safer for trans and gender diverse youth(external link) Inside Out, NZ, 2016

Youth’12 – fact sheet about transgender young people(external link) Gender Minorities Aotearoa

First steps – shared stories from parents and caregivers of trans* and gender diverse children(external link) Working It Out, Australia

Information and Support Directory - Intersex/Trans/Non-binary/Takatāpui/MVPFAFF re.frame, NZ, 2018

The genderbread person(external link) itspronouncedmetrosexual.com

Transgender people and suicide(external link) Centre for Suicide Prevention, Canada

Safe transition(external link) Willis St Physiotherapy, NZ, 2019

Information for parents

What if my child has gender dysphoria?

All children explore different ways of expressing their gender. Many children do not conform to their culture’s expectations for boys or girls, and many boys prefer dolls and dressing up in skirts and many girls prefer short hair and refuse to wear dresses. Most of these children are comfortable with the sex they were assigned at birth.

However, some children persistently assert themselves as a gender different from the sex assigned at birth. These transgender children are usually insistent, consistent and persistent in their gender identity and may exhibit distress or discomfort with their physical body.

Some children are aware of their gender identity from an early age, while others may take some time to figure it out. Children can be aware of the disapproval of those around them and may try and hide their feelings about their gender.

What should I do if my child is questioning their gender?

Family acceptance and support significantly reduces depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts that transgender youth experience. Your acceptance and encouragement of your child is vital to their health and wellbeing. You can do this by:

- reassuring your child that they have your unconditional love and support, regardless of their gender identity

- providing your child with a safe space in which to explore their gender

- encouraging their exploration of how they express themselves and allowing them to present in the way they feel most comfortable, eg, clothes, hairstyle, creativity

- using your child’s preferred gender pronouns (he/him, she/her, they/them etc) and preferred names

- when your child is ready, supporting family and friends to do the same, providing it is safe to do so.

What about medical interventions?

For children who assert they have a mismatch between their sex and gender, including those who may identify as transgender, no medical intervention is needed pre-puberty.

If your child is born intersex, it’s recommended you wait until your child is old enough to choose their own gender identity before any surgery is carried out.

However, you may want to talk to a paediatrician, mental health professional or parent support group to work out how to best support your child or family member. This is particularly important if there is associated distress related to gender identity.

What about when my child reaches puberty?

Where these feelings continue into or emerge during puberty, particularly if associated with distress, it is important to see a health professional. Puberty blockers are a medication that can be used to halt the physical changes of an unwanted puberty.

Blockers are a safe and fully reversible medicine that may be used from early puberty through to later adolescence to help ease distress and allow time to fully explore gender health options.

Service providers that can help access blockers include:

- paediatric services

- youth health services

- endocrinologists

- primary health care teams.

Support for parents

Portal support for NZ parents of transgender and gender diverse children(external link) A Facebook group offering support for parents with children who are gender questioning or gender diverse. Email contact at nzparentsoftransgenderchildren@gmail.com.

References

- Trans and gender diverse people(external link) Better Health, Australia, 2018

- Transgender New Zealanders(external link) Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora

- Gender dysphoria(external link) NHS Choices, UK, 2016

- Gender dysphoria(external link) Mental Health Foundation, NZ, 2022

- Health care for transgender New Zealanders(external link) Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora

- Gender dysphoria(external link) Patient Info, UK, 2018

- What we know project(external link) Cornell University, US, 2018

- Feminising hormone therapy(external link) Mayo Clinic, US, 2021

- Bustos VP, Bustos SS, Mascaro A, Del Corrall G, Forte AJ, CiudadP, et al. Regret after gender-affirming surgery – a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence(external link) Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2021;9:23477.

- Transgender and gender diverse tamariki and rangatahi(external link) Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora

- Gender identity(external link) Common Ground, NZ

Service

Pae Ora ki Waitaha(external link) is a healthy lifestyles promotion service developed in consultation with Kaupapa Māori and Pacific Peoples providers to support priority populations (including LGBTQIA+) to access holistic health improvement programmes in the Canterbury area.

Other guidelines and resources

Supporting Aotearoa's rainbow people – a practical guide for mental health professionals(external link) Rainbow Mental Health, NZ, 2019 English(external link), te reo Māori(external link), Chinese(external link)

Guidelines for gender affirming healthcare for gender diverse transgender children, young people and adults(external link) Transgender Health Research Lab, University of Waikato, NZ, 2018

Transgender services(external link) Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora

Gender reassignment health services – good practice guide for health professionals(external link) Counties Manukau DHB, NZ, 2011

Intersex roundtable report and project(external link) Human Rights Commission, NZ, 2016

Clinical guidelines for the management of disorders of sex development in childhood(external link) Intersex Society of North America, US, 2006

Australia and NZ Professional Association for Transgender Health(external link)

Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people(external link) The World Professional Association for Transgender Health

Identifying and managing young people with mental health problems(external link) BPAC, NZ 2017

A “how-to guide” for a sexual health check-up(external link) BPAC, NZ, 2013

Managing frequently encountered mental health problems in young people – non-pharmacological strategies(external link) BPAC, NZ, 2015

Addressing mental health and wellbeing in young people(external link) BPAC, NZ, 2015

Gender dysphoria in adults – an overview and primer for psychiatrists(external link) Transgender Health, 2018

Professional development(external link) Gender Minorities Aotearoa

Healthcare presentation at NZ Sexual Health Society Conference(external link) Gender Minorities Aotearoa, 2019

Continuing professional development

Diversity and inclusive primary healthcare: Trans 101 (external link)(PHARMAC Seminars, NZ, 2017)

Gender diversity (external link)(PHARMAC Seminars, NZ, 2017)

Supporting gender diversity in primary care (external link)(Goodfellow Symposium, NZ, 2017)

(external link)Webinar – working with gender diverse clients(external link) (Goodfellow Unit, NZ, 2017)

Apps

Brochures

Tīwhanawhana Trust and Mental Health Foundation, NZ, 2021

itspronouncedmetrosexual.com

RainbowYOUTH, NZ, 2019

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust.

Reviewed by: Sex and Gender Diverse Health and Outcomes Working Group, Capital and Coast DHB

Last reviewed:

Page last updated: