Bronchiectasis in adults | Pūkahukahu hauā

Key points about bronchiectasis

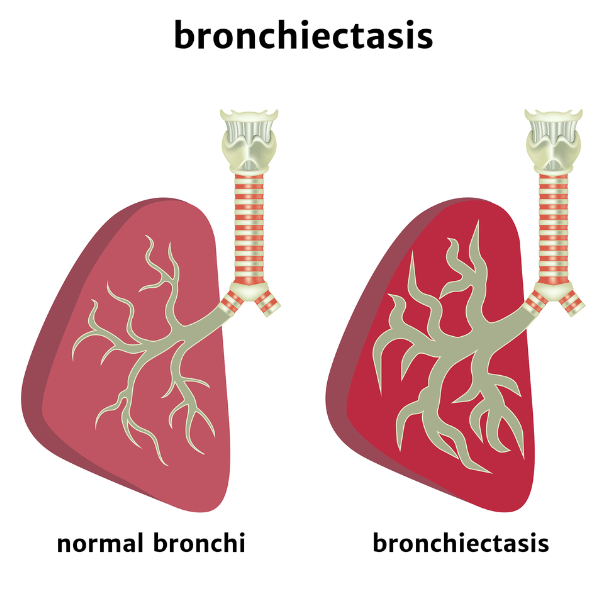

- Bronchiectasis (pūkahukahu hauā) is a long-term lung condition where your airway walls have become damaged, widened and thickened.

- The damaged airways can cause mucus to build-up leading to infections, chronic inflammation, and an ongoing chesty cough and shortness of breath.

- There's no cure but good treatment stops it getting worse.

- If you have bronchiectasis and you're coughing or bringing up more phlegm than normal, are more short of breath or coughing up blood, or have a fever or new chest pain seek medical help.

Bronchiectasis is where your airways (the branching tubes of your lungs) are damaged and become wider and floppier than normal. Damage to the walls of the breathing tubes and the small hairs that help to clear the airways lead to mucus build up. Over time it becomes harder to cough the mucus up. Bacteria grow in the mucus and can cause lung infection which can result in ongoing inflammation and more damage.

Image credit: Depositphotos

Each new infection causes more damage to your airways, making them wider, thicker and floppier. Your lungs struggle to move air in and out and your airways struggle to clear out mucous, leading to continuous coughing and shortness of breath.

Over time, bronchiectasis can get worse, making day-to-day activities harder to do. It can also lead to long stays in hospital and reduce your life span. With early diagnosis and treatment, ongoing airway damage can often be reduced.

The video below shows what happens to your airways.

Video: Bronchiectasis animation – what is bronchiectasis?

Bronchiectasis is caused by damage to your airway walls. It begins most often in early childhood but can develop at any age. In up to half of cases the cause is unknown, but known causes include:

- Infection: Certain lung infections can cause bronchiectasis in some people. Some bugs that can cause it are pertussis, measles and influenza.

- Weakened immune system: This is where your immune system isn't able to fight infections properly. You can be born with this – called primary immunodeficiency – or get it later from another condition such as HIV.

- Poor mucus clearance: Some conditions, such as cystic fibrosis or primary ciliary dyskinesia, mean you can't clear mucus properly.

- Other causes: These include inhaling noxious chemicals, and autoimmune conditions. You can even be born with it.

Smoking is not a major cause – many people with bronchiectasis have never smoked. However, because smoking irritates your lungs it makes the condition worse.

The main symptoms of bronchiectasis are coughing up lots of mucus (phlegm) and a long-term wet-sounding cough. The phlegm can be clear or different colours. Other symptoms include:

- shortness of breath

- wheezing

- chest pain.

You may also feel tired and generally unwell.

If you have a wet-sounding cough that lasts for weeks, see your healthcare provider

How is bronchiectasis diagnosed?

Your healthcare provider will talk to you about your symptoms and examine you. They may do some or all of these tests:

- Blood tests.

- Breathing test (called pulmonary function test).

- Chest X-ray.

- CT scan.

- Sputum/phlegm test.

- Looking into your airways with a camera if you are coughing up blood.

How is bronchiectasis treated?

The main aims of treatment are to keep your airways open, reduce mucus build-up and prevent further damage to your lungs.

Chest physiotherapy

A physiotherapist can show you how to clear your lungs of extra mucus and teach you exercises to do at home. You'll need to do this once or twice a day.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

In pulmonary rehabilitation you are taught ways to improve your symptoms. You may learn about your condition, ways to pace yourself and how to start or continue with an exercise programme. Read more about pulmonary rehabilitation.

Antibiotics

Your doctor may prescribe a course of antibiotics if you have signs of an infection. It's important to finish the course even if you feel better, as stopping the antibiotics too soon could cause the infection to come back quickly. Often a 2-week course of antibiotics is required. If you have frequent chest infections, you may be prescribed antibiotics to take long term.

There are a number of things you can do to help relieve the symptoms of bronchiectasis and stop the condition getting worse.

- Have a bronchiectasis plan: This is a written document about what you need to do to manage your bronchiectasis well. Read more about bronchiectasis action plans below.

- Avoid smoking: Smoking irritates your lungs and will make the condition worse.

- Keep yourself well hydrated: Drinking plenty of fluid, especially water, helps prevent mucus from becoming thick and sticky. Keeping mucus moist and slippery makes it easier to cough up.

- Vaccinations: To help protect you from some infections, get the flu and COVID-19 vaccination every year. Pneumococcal vaccination is also recommended, but this isn't funded for most adults. This vaccine protects you from some of the kinds of bacteria that cause pneumonia. Contact your healthcare provider for this.

- Chest physiotherapy: This should be done once or twice a day at home when you are well, and more often if you're sick.

- Exercise regularly: Being physically active helps keep your chest free of infection by helping to clear the mucus. Aim to exercise at least 3 or 4 times a week. Any type of exercise that makes you take long, deep breaths is good. It’s okay if you cough during exercise.

- Eat a balanced diet: Read more about healthy eating.

- Keep your home warm and dry: Read more about keeping your home warm in winter.

Apps reviewed by Healthify

You may find it useful to look at some Breathing apps.

Bronchiectasis action plan

If you have bronchiectasis, talk to your healthcare provider about drawing up a bronchiectasis action plan. This is a written document about what you need to do to manage your bronchiectasis well. It means you don't need to rely solely on remembering what your healthcare provider told you to do.

A bronchiectasis action plan has information on how to recognise and handle worsening symptoms, and when, how and who to contact in an emergency. Some people need antibiotics on hand at home for prompt treatment of flare-ups.

Here are some bronchiectasis action plans:

- My blue card action plan [PDF, 367 KB] District Health Boards, NZ.

- Bronchiectasis action plan(external link) Bronchiectasis, Australia.

- Bronchiectasis action plan(external link) Asthma + Respiratory Foundation, NZ

Support

Asthma New Zealand(external link) provides education, training and support to anyone with bronchiectasis and their whānau.

Stories about people living with bronchiectasis.

Esther-Jordan Muriwai's story

Listen to Esther's story and hear her passion for creating a place for people with bronchiectasis and their families. Esther was the founder and has been the inspiration for her whānau, community and health professionals to set up the Bronchiectasis Foundation of NZ. Visit the Bronchiectasis Foundation(external link) for more of Esther's story and information about bronchiectasis.

Video: Camron Muriwai and Ana Sadlier: Bronchiectasis Foundation I NZ Respiratory Conference 2015

(Asthma Foundation NZ, 2015)

Chloe's story

Chloe is a fun-loving 4-year-old who was diagnosed with bronchiectasis at 3 years old in August 2016. As an infant, she experienced repeated chest and breathing issues and had multiple admissions to hospital with bronchiolitis. At the age of 2, she was diagnosed with asthma. Then a severe case of influenza in July 2015 further damaged her lungs and it took 2 months for her to recover. A visit to Starship hospital in August 2016 confirmed Chloe now had bronchiectasis.

Read Chloe's story on the Bronchiectasis Foundation(external link) website.

Katie's story

Katie was diagnosed with bronchiectasis at the age of 8 years old. This followed 7 bouts of pneumonia during the 15 months before this.

"In February 2013 we met Esther-Jordan Muriwai. She had bronchiectasis too. Sometimes we were both sick and in hospital at the same time so we visited each other. Esther told me that if I don’t do my physio I would end up very sick like she was. She encouraged me to do my daily physio and medications. Esther showed me that I can do anything I want to do in my life … I don’t need to let my lung disease stop me from doing things, especially when I am well. Having bronchiectasis doesn’t mean you have to be left out of things.

"To help me stay well I take medication and inhalers, and do twice-daily physio and nebuliser. Sometimes I don’t want to do my physio but I know I have to otherwise I get sicker and go into hospital more often. And this means I miss out on fun things in life like horse riding, swimming lessons, hanging out with my friends, going to school and going to Girl Guides."

Katie and her family worked with Esther talking to newspapers and television and continue to work hard to raise awareness of bronchiectasis.

Read more of Katie's story on the Bronchiectasis Foundation(external link) website.

Video: A 'pretty normal life' – Julie Blamires' research into young people living with bronchiectasis

This short video reports the findings from a qualitative study where she interviewed 15 young people with bronchiectasis. They described what their life was like and what was most important to them.

(Julie Blamires, NZ, 2021)

Video: Bronchiectasis – 3 part video series (Edward and Piri's stories)

In this 3 part video series Edward learns that he has bronchiectasis, a disease which his grandfather died from at a young age. Meanwhile 17 year old Piri's whanau have gathered at Starship hospital to try to convince him to be proactive about getting to hospital as soon as his bronchiectasis symptoms re-appear.

(Faultline Films NZ, 2010)

(Faultline Films NZ, 2010)

(Faultline Films NZ, 2010)

Find more personal stories at:

Bronchiectasis(external link) Bronchiectasis Foundation, NZ

Bronchiectasis(external link) KidsHealth, NZ

Bronchiectasis(external link) Asthma + Respiratory Foundation, NZ

Apps

Resources

Bronchiectasis action plan (adult)(external link) Asthma + Respiratory Foundation, NZ

Regional Blue card COPD Action plan [PDF, 355 KB] District Health Boards, NZ

Bronchiectasis action plan(external link) Northland DHB, NZ

Living with bronchiectasis – things to know(external link) Asthma + Respiratory Foundation, NZ

References

- Bronchiectasis – rates still increasing among Pacific peoples(external link) BPAC, NZ, 2012

- Bronchiectasis management(external link) Starship Clinical Guidelines, NZ, 2022

- Bronchiectasis(external link) Bronchiectasis Toolbox, Australia

- Bronchiectasis(external link) Speak Up in BE, US

Key facts and figures

Source: The impact of respiratory disease in NZ – 2018 update(external link)

Although bronchiectasis is the rarest of the indicator conditions, the bronchiectasis hospitalisation rate increased by a significant 45% over the study period. Mortality rates increased by 88%.

Being of Māori or Pacific ethnicity was a significant risk factor for bronchiectasis hospitalisation and death, and Asian mortality rates were also higher than non-MPA. The greatest disparity in hospitalisations by age and ethnicity was for Pacific peoples aged over 65 years, whose bronchiectasis hospitalisation rates of 490.5 per 100,000 were 5.94 times higher than for non-MPA. Overall, Pacific peoples were 6.2 times more likely to be hospitalised for bronchiectasis than non-MPA, and Māori were 3.8 times more likely to be hospitalised, while Asian peoples rates were not significantly different. Mortality differences were similar for Māori and Pacific, but 1.7 times the non-MPA rate for Asian peoples.

Bronchiectasis also showed strong socio-economic disparity, with hospitalisation rates 2.5 times higher in the most deprived compared to the least deprived neighbourhoods, and mortality rates 1.8 times higher. The hospitalisation rate increase for the most deprived quintile was steepest for Māori.

Clinical resources

Preventing and managing bronchiectasis in high-risk paediatric populations(external link) BPAC, NZ, 2020

Navigating uncertainty – managing respiratory tract infections(external link) BPAC, NZ, 2019

Te ha ora – the breath of life – national respiratory strategy(external link) Asthma & Respiratory Foundation of NZ, 2015

Bronchiectasis – acute respiratory exacerbation(external link) Starship Children's Hospital, NZ, 2021

Bronchiectasis – rates still increasing among Pacific peoples(external link) BPAC, NZ, 2012

Using nebulisers safely(external link) BPAC, NZ, 2008

, et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for bronchiectasis in adults(external link)

Continuing professional development

Bronchiectasis update by Dr Conroy Wong (external link)(The Goodfellow Unit, NZ, 2018)

Brochures

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust.

Reviewed by: Dr Art Nahill, Consultant General Physician and Clinical Educator

Last reviewed: