Targeted therapy to treat cancer

Key points about targeted therapy to treat cancer

- Targeted therapy is a group of medicines that target damaged genes or proteins of cancer cells to stop the cancer growing and spreading.

- Depending on the type of cancer you have, targeted therapy may be a treatment option. It can be used alone or in combination with other treatments such as chemotherapy, surgery or radiation.

- Find out more about targeted therapy.

Targeted therapy is a group of medicines that target damaged genes or proteins of cancer cells to stop the cancer growing and spreading. Depending on the type of cancer you have, targeted therapy may be a treatment option. It can be used alone or in combination with other treatments such as chemotherapy, surgery or radiation.

Each type of targeted therapy blocks specific targets, such as damaged proteins or genes, in or on cancer cells. By interfering with these targets, these medicines can slow cancer growth or kill the cancer cells. This reduces cancer symptoms while causing minimal harm to healthy cells.

There are many different types of targeted therapy medicines. They are grouped based on how they work. The 2 main groups are monoclonal antibodies and small molecule inhibitors.

Targeted therapy can be given on its own or in combination with other types of treatment such as chemotherapy, surgery or radiotherapy.

When is targeted therapy used?

Targeted therapy may be used:

- before surgery to reduce the size of a cancer

- after surgery to destroy any remaining cancer cells

- to treat cancer, after other treatments, if the cancer has come back or hasn’t responded

- as initial treatment for advanced cancer that has certain gene changes

- as long-term treatment to try to prevent the cancer coming back or growing.

Targeted therapy is not for everyone

Targeted treatment only works if a cancer cell has the specific gene or protein that the medicine is trying to block, so it isn’t given to everyone. Most targeted treatments are either monoclonal antibodies or small molecule inhibitors. For some types of cancer, your cancer specialist will test a sample of your cells to see if the cells contain the target that is allowing the cancer to grow. People with the same cancer type may be offered different treatments based on their test results.

Over time, cancer cells may stop responding to a targeted therapy medicine, even if it worked at first. If this occurs, another targeted therapy or a different type of treatment may be recommended. In rare cases, targeted therapy can cause serious side effects, and your treatment plan may need to be adjusted, for example, by lowering the dose or switching to another medicine.

Is targeted therapy the same as chemotherapy?

No, targeted therapy and chemotherapy are not the same. They work in different ways to treat cancer.

- Targeted therapy mainly focuses on the cancer cells, and in this way limits damage to healthy cells and their side effects.

- Chemotherapy attacks cells as they divide and can kill both cancerous and healthy cells in the process.

Targeted therapy works by disrupting certain pathways or molecules that cancer cells rely on to grow and spread. They can work in one or more of the following ways:

- Blocking signals inside or outside cancer cells that prevents them growing and dividing.

- Deliver cell-killing substances to specific cancer cells, damaging their DNA and causing them to die.

- Block new blood vessels in tumours which slows their growth or cause them to shrink.

- Activate the immune system to destroy the cancer cells.

You can see how targeted therapy works in the video below.

Video: What are targeted therapies?

Targeted therapy can be given in different ways depending on the type of cancer being treated and the medicine used. The type of targeted therapy, amount you are given, how often, and how long will vary depending on the type of cancer and how you respond. Some people are prescribed daily dosing of these medicines while some people need to follow a dosing schedule, for example every month.

Targeted therapy can be given:

- as tablets or capsules that you swallow (orally)

- by injection or infusion through a vein (called IV infusion)

- as an injection under your skin.

When targeted therapy is given through an infusion, some people may have side effects such as skin rash, feeling sick, or trouble breathing. These reactions can happen during the infusion or a few hours later. To keep you safe, the healthcare team will watch you closely and may give you medicine to help prevent reactions. Reactions are more common with the first few infusions, so they may be given at a slower rate than later treatments.

How long will I need targeted therapy?

The length of time you take targeted therapy depends on the goal of treatment, how well your cancer responds, and any side effects you experience. In many cases, targeted therapy tablets or capsules are taken every day for several months or even years.

The immune system naturally makes proteins called antibodies to fight infections. Monoclonal antibodies are man-made versions of these proteins. They attach to specific proteins on cancer cells or nearby cells to affect how the cancer grows. Some monoclonal antibodies are also considered a type of immunotherapy because they help the immune system attack cancer.

There are a few different monoclonal antibodies that target different proteins or cells.

HER2-targeted medicines

- Examples include trastuzumab.

- High levels of the protein human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) cause cancer cells to grow uncontrollably, especially certain breast, stomach, lung and ovarian cancers. HER2-targeted medicines destroy the HER2 positive cancer cells or reduce their ability to divide and grow.

Angiogenesis inhibitors

- Examples include bevacizumab.

- Angiogenesis inhibitors specifically act on a protein called vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). This protein helps cancer cells grow a new blood supply. Targeting VEGF reduces the supply of oxygen and nutrients to the cancer cells. This can shrink the cancer or stop it growing.

Anti-CD20

- Examples include rituximab and obinutuzumab.

- These medicines target a protein called CD20 found on some B-cell leukaemias and non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

EGFR inhibitors

- Examples include cetuximab.

- Cetuximab attaches to a protein called EGFR on the surface of cancer cells. By blocking this protein, it helps stop the cancer cells from growing and dividing.

Some monoclonal antibodies work like immunotherapies by attaching themselves to specific proteins on cancer cells.

Small-molecule inhibitors are other types of targeted treatment that are not monoclonal antibodies. Small-molecule inhibitors block a target inside a cancer cell to stop its action.

Tyrosine-kinase inhibitors

- Examples include imatinib, sunitinib, dasatinib, axitinib, dabrafenib, erlotinib, gefitinib, ibrutinib, lenvatinib, midostaurin, nintedanib, nilotinib, pazopanib and osimertinib.

- These medicines block proteins called tyrosine kinases from sending signals that tell cancer cells to grow, multiply and spread. Without this signal, the cancer cells may die.

MEK inhibitors

- Examples include trametinib.

- It works by blocking MEK proteins, which are part of a pathway that helps cancer cells grow and divide.

PARP inhibitors

- Examples include olaparib.

- Olaparib blocks a protein called poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), that repairs damaged DNA in cancer cells. Without this repair system, the cancer cells become weaker and eventually die, especially in cancers with BRCA gene mutations where DNA repair is already faulty.

mTOR inhibitors

- Examples include everolimus.

- Everolimus blocks a protein called mTOR, which helps cancer cells grow, divide, and survive. By stopping mTOR, everolimus slows cancer growth and can make cancer cells more likely to die.

CDK inhibitors

- Examples include palbociclib, ribociclib and abemaciclib.

- These medicines block cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) from sending signals that tell cancer cells to grow, multiply and spread. Without this signal, the cancer cells may die.

Targeted therapy can cause side effects but because the medicines target cancer cells, they generally cause less damage to healthy cells, leading to fewer side effects compared to chemotherapy or radiation. While side effects do happen, they are often milder and easier to manage.

The side effects of targeted therapy differ from person to person, and not everyone will get the same side effects. The following are common side effects of targeted therapy. The chances of getting these side effects differs between the medicines. It's important to talk to your healthcare team about possible side effects before you start treatment and any side effects you get while on treatment. The following is a guide.

Fatigue

Fatigue or tiredness, low energy and difficulty performing everyday tasks is usually from the effects of targeted therapy on healthy cells. The physical and emotional stress of treatment itself can also cause feelings of fatigue.

What you can do:

If you do get tired, try to take things easier. Only do as much as you feel comfortable doing. Try to plan rest times in your day. Also try to drink plenty of fluids, eat well and do some gentle physical activity. This will help you cope better with the treatment. Don't be afraid to ask for some help. Family, whānau, friends and neighbours may be happy to have the chance to help you – tell them how they can help. If you're not sleeping well, tell your healthcare team. They may be able to suggest ways to help you sleep.

Tummy (stomach) problems

These include nausea (feeling sick), vomiting (being sick), diarrhoea (runny poo), constipation or tummy pain.

What you can do:

Talk to your healthcare team about these side effects – they may be able to prescribe medicines to relieve this. Eat smaller meals more often to ease nausea and improve digestion. Avoid spicy, greasy, or heavy foods that may trigger tummy problems. To prevent constipation, eat foods high in fibre.

Skin problems

These include rash, dry skin, itching or changes in skin colour.

What you can do:

Use a lotion or cream to stop getting dry skin. Apply it while your skin is still damp after washing. Avoid perfumes, cologne, or aftershave lotion that could irritate and dry out the skin. Avoid long, hot showers that can dry the skin. Have short, cooler showers or sponge baths. It is important to cover up your skin and use a high protection sunscreen (SPF 30+) if you are out in the sun when having chemotherapy. If you're having injections, your skin may go red or thicken where the injection or the drip goes in. If this happens, tell your healthcare team immediately. Tell your healthcare team as soon as possible about any skin problems.

Loss of appetite

Some people may not feel like eating at all. Changes to your appetite can be because of your treatment, your cancer or just because of the whole experience of having cancer and being treated for it. Your sense of taste may change.

What you can do:

Try different foods until you find foods that you enjoy. Eat smaller amounts more often or try drinking liquid supplements you can get from your pharmacist. Even when you're not able to eat very much, it's important to drink plenty of clear fluids.

Sleep problems

This may include changes to your sleep pattern, problems falling asleep or staying asleep, insomnia or extreme sleepiness.

What you can do:

While getting enough good sleep each night is very important for health and wellbeing, try to rest and relax when you can. If you have been lying awake for a while, try getting up and doing something relaxing, such as listening to music or reading. Go back to bed when you feel sleepy. Try not to look at the time and become frustrated with how long you have been awake or how much sleep you are missing. Try light activities during the day such as walking or gentle stretching for relaxation. It’s best to start slowly and follow an exercise plan recommended by your healthcare team.

Other side effects

- Increased blood pressure: Your healthcare team will monitor your blood pressure regularly.

- Hand-foot syndrome which is redness, tenderness, swelling, and peeling of the skin on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet: Let your healthcare team know if this happens to you.

- You may have an increased risk of infection: Let your healthcare team know if you feel unwell, and try to avoid crowded areas, and people with known infections such as shingles or chickenpox.

Chemotherapy(external link), immunotherapy(external link), targeted treatment(external link) Cancer Society, NZ

Targeted treatments(external link) Cancer Society, NZ

Understanding targeted therapy(external link) Cancer Institute NSW

Living well with cancer – eating well [PDF, 5.5 MB] Cancer Society, NZ English/te reo Maori [PDF, 5.5 MB]

Brochures

Medicines and side effects [PDF, 91 KB](external link) Healthify He Puna Waiora, NZ, 2024

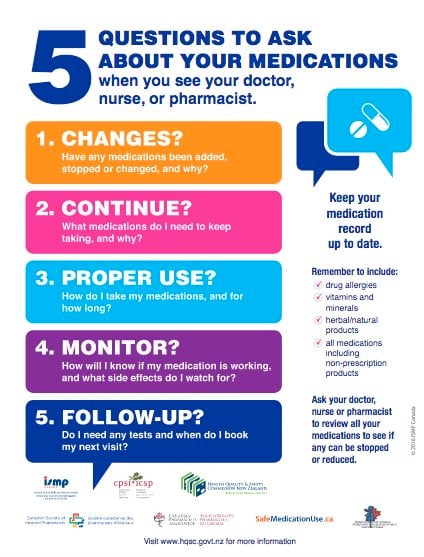

5 questions to ask about your medications(external link) Health Quality and Safety Commission, NZ, 2019 English(external link), te reo Māori(external link)

Living well with cancer – eating well Cancer Society, NZ English/te reo Māori

Chemotherapy, Immunotherapy and Targeted Treatment(external link) Cancer Society, NZ, 2019

References

- Targeted therapy(external link) American Cancer Society

- Targeted therapy to treat cancer(external link) National Cancer Institute, US

Brochures

Chemotherapy, Immunotherapy and Targeted Treatment

Cancer Society, NZ, 2019

Medicines and side effects

Healthify He Puna Waiora, NZ, 2024

Health Quality and Safety Commission, NZ, 2019 English, te reo Māori

Credits: Sandra Ponen, Pharmacist, Healthify He Puna Waiora. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust.

Reviewed by: Joanna Buchanan, Oncology Pharmacist, Auckland; Angela Lambie, Pharmacist, Auckland

Last reviewed: