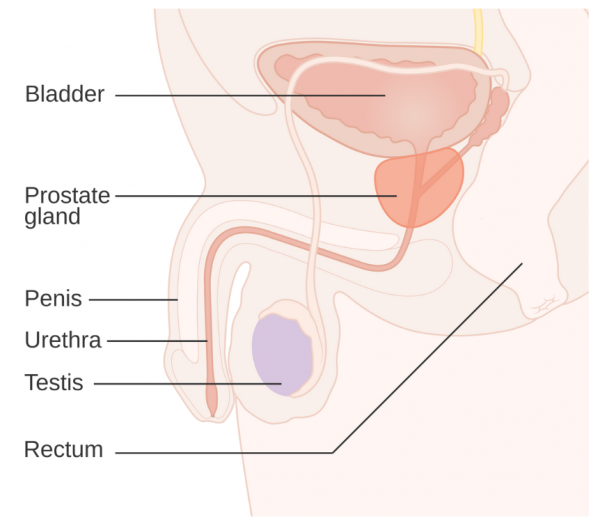

Checks for prostate cancer involve a blood test, called the prostate specific antigen (PSA) test and, often, a digital rectal examination (DRE).

The prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test

This test measures the level of PSA in your blood. PSA is a protein made by your prostate. Some of the protein leaks into your blood, but how much depends on your age and the health of your prostate. Higher than normal PSA levels can be caused by many prostate problems such as an infection, an enlarged prostate or prostate cancer.

PSA tests aren't routinely used to screen for prostate cancer because results can be unreliable.

- Your PSA level can be raised by other non-cancerous conditions.

- Most men with raised PSA levels don’t have prostate cancer. This is called a false positive result. 3 in 4 men (75%) with a raised PSA don't have cancer.

- Some men with prostate cancer have normal PSA levels. This is called a false negative result. 8 to 10 men in 100 (8 to 10%) with prostate cancer have a normal PSA level. Some of these cancers can be found with a digital rectal examination (DRE). However, high PSA levels are a risk factor for prostate cancer.

Digital rectal examination

This is a quick way for your healthcare provider to check for prostate problems. They will feel the size and shape of your prostate by inserting a gloved and lubricated finger into your rectum (bottom). A prostate that is rough, irregular or hard is more likely to have cancer. Most cancers are too small to be found by a rectal examination. However, some prostate cancers that would be missed by PSA screening can be found this way.

Prostate enlargement is very common, about 1 in 2 men over 50 years of age has an enlarged prostate. Most of these men do not have prostate cancer. Read more about prostate enlargement.

Specialist referral

Your healthcare provider will discuss your prostate cancer screening results with you. If the PSA or DRE results suggest you have a high risk for prostate cancer, you will be referred to a urologist (a doctor who specialises in urinary and prostate conditions).

You’ll need to decide whether to have further testing and possibly treatment. In making this decision, you’ll need to consider whether your quality of life will be better living with what may be a slow-growing cancer or having treatments which may cause you more harm than the cancer will.

Radiology

You may be asked to have an MRI and/or an ultrasound scan.

- An MRI can be done to see if your prostate is larger than expected, and whether there are any abnormal looking areas. It can help work out whether you have cancer and which part of your prostate is affected.

- An ultrasound can provide an image of the internal part of your prostate. It’s done rectally (by putting an ultrasound probe into your rectum/bottom). A biopsy may be done at the same time.

Biopsy

The urologist will talk to you about having a prostate biopsy. This is when small samples of your prostate gland cells are taken with a needle for examination. Your skin is numbed with local anaesthetic for this test.

The aim of the biopsy is to help confirm whether or not you have prostate cancer and, if so, whether it needs treatment. The urologist will then discuss treatment options with you.

If the biopsy doesn’t show any sign of cancer, you may be advised to attend future check-ups so your progress can be monitored.

Up to 2 in 100 people with a prostate (2%) get side-effects from the biopsy. This can be bleeding, infection or not being able to pee for a few days. Biopsies don't find all cancers.