You can now add Healthify as a preferred source on Google. Click here to see us when you search Google.

Pulmonary embolism | Pūkahukahu poketoto

Also known as 'PE'

Key points about pulmonary embolism

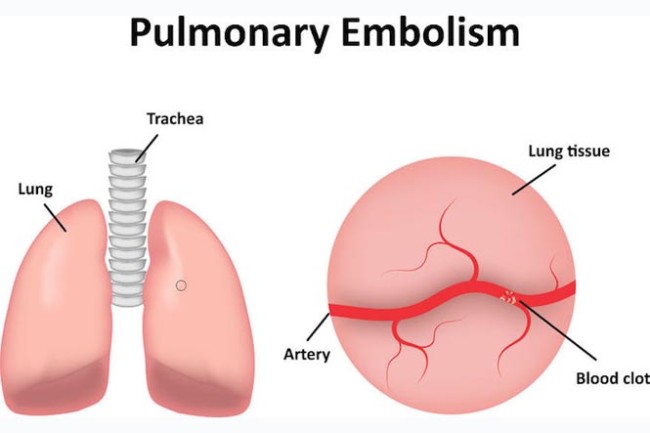

- Pulmonary embolism (pūkahukahu poketoto) is a blockage in one of the blood vessels in your lungs.

- It most commonly happens when a blood clot that has formed in the leg travels to the lungs where it gets lodged in a blood vessel and blocks the normal flow of the blood.

- Pulmonary embolism can be life-threatening because the clots block blood flow to the lungs. However, quick treatment greatly reduces the risk of death.

- Taking steps to prevent blood clots in your legs is key to helping protect against pulmonary embolism.

A pulmonary embolism (pūkahukahu poketoto) is a blockage in one of the blood vessels in your lungs. It most commonly happens when a blood clot that has formed in your leg travels to your lungs where it gets lodged in a blood vessel and blocks the normal flow of the blood.

It can be life-threatening if it's not treated.

Most often pulmonary embolism is caused by blood clots that travel to the lungs from the deep veins of the legs. Rarely, the clot can come from another part of the body.

Image credit: 123rf

Blood clots that form in the deep veins of the body are known as deep vein thrombosis (DVT). They often develop after long periods of inactivity, such as when you are immobilised after surgery or illness.

Sometimes blockages in the blood vessels are caused by substances other than blood clots, such as:

- fat from the marrow of a broken long bone (example, from a fracture)

- air bubbles (example, from injections or surgical procedures, scuba diving or injury to the lung)

- part of a tumour.

Many factors that increase your risk of developing DVT, also increase your risk of pulmonary embolism. The more risk factors you have, the greater your risk. Read more about who is at risk of DVT.

| Risk factors | Description |

| Being inactive for long periods of time |

|

| Surgery and injury (trauma) |

|

| Increased hormones (oestrogen and progestin) |

|

| Pregnancy |

|

| Medical conditions |

|

| Lifestyle factors |

|

The symptoms of pulmonary embolism can be different for different people, depending on the size of the clots, how much of your lung is involved and whether you have underlying lung or heart disease.

Pulmonary embolism can be life-threatening

Seek immediate medical attention if you experience any of the symptoms below:

| Symptoms | Description |

|---|---|

| Shortness of breath | This symptom typically appears suddenly and always gets worse with exertion. |

| Chest pain | You may feel like you're having a heart attack. The pain may become worse when you breathe deeply, cough, eat, bend or stoop. The pain will get worse with activity or exertion but won't go away when you rest. |

| Cough | The cough may produce bloody or blood-streaked phlegm or spit. |

Other signs and symptoms that can occur with PE:

- Swelling or leg pain of one or both legs, usually in the calf.

- Cold, damp skin that turns bluish grey.

- Fever.

- Excessive sweating.

- Fast or irregular heartbeat.

- Light-headedness or dizziness.

Pulmonary embolism can be difficult to diagnose, especially in people who already have heart or lung disease. For that reason, your doctor will ask you about your symptoms and is likely order one or more of the following tests:

Blood tests

Your doctor may order a blood test for D dimer, a protein fragment that's made when a blood clot dissolves in your body. High levels may suggest an increased chance of blood clots. Blood tests also can measure the amount of oxygen and carbon dioxide in your blood. A clot in a blood vessel in your lungs may lower the level of oxygen in your blood.

Chest X-ray

This shows images of your heart and lungs on film. Although X-rays can't diagnose PE and may even appear normal when pulmonary embolism exists, they can rule out conditions that seem just like pulmonary embolism.

Other tests

Your doctor may also perform other tests such as CT scan, electrocardiogram (ECG), ultrasound and MRI to rule out any other causes of your symptoms.

The main aim of treatment is to prevent the clot from getting any bigger and prevent new clots from forming. Because pulmonary embolism is life threatening, immediate treatment is vital. Treatment options include:

Medications

| Medication | Examples |

|---|---|

|

Anticoagulants |

Anticoagulants are often referred to as ‘blood thinners’ but they actually work by interrupting the clot-forming process and increasing the time it takes for clots to form. This helps prevent blood clots from forming and stops existing clots from getting bigger. Common examples of anticoagulant medications are:

You may require regular blood tests to check how well the anticoagulants are working and if dosage changes for warfarin are required. Anticoagulant treatment is usually continued for at least 3 months to be fully effective in treating a pulmonary embolism. In some cases, it may be required on a long-term basis. |

|

Clot dissolvers (thrombolytics) |

While clots usually dissolve on their own, there are medications given through the vein that can dissolve clots quickly such as alteplase. Because these clot-busting drugs can cause sudden and severe bleeding, they usually are reserved for life-threatening situations. |

Filters

Filters can be placed in a large vein to stop any more blood clots from reaching the lung. This procedure does not need an anaesthetic and can be done at the bedside. Filters are useful if anticoagulant treatment on its own is not enough, or for patients who cannot have anticoagulant treatment for some reason.

Surgery (embolectomy)

Removal of the clot in the lung, by surgery, is only considered as a last resort for very ill patients with a massive pulmonary embolism. This is because the operation itself carries a significant risk of death. The operation involves surgery inside the chest, close to the heart. It requires a specialist hospital and surgical team and is only considered as an option when the risk of dying from the pulmonary embolism is even greater.

A pulmonary embolism is a serious condition and can have a high risk of death but this is greatly reduced by early treatment in hospital.

- If a pulmonary embolism is treated promptly, the outlook is good, and most people can make a full recovery.

- The outlook is less good if there is an existing serious illness which helped to cause the embolism such as in advanced cancer.

- A massive pulmonary embolism is more difficult to treat and is life-threatening.

- The riskiest time for complications or death is in the first few hours after the blockage occurs.

- There is a high risk of another pulmonary embolism occurring within 6 weeks of the first one. This is why treatment is needed immediately and is continued for about 3 months.

Have you been recently diagnosed with a blood clot (thrombosis / DVT / pulmonary embolism)? Thrombosis UK have developed a series of short films to help share information about blood clots.

Video: Understanding blood clots – Recovering from a pulmonary embolism

This video may take a few moments to load.

(Thrombosis UK, 2019)

Video: Understanding blood clots – Diagnosed with a pulmonary embolism (PE) at just 22

This video may take a few moments to load.

(Thrombosis UK, 2019)

Video: Zoe's experience with pulmonary embolism

Zoe Williams, a fit young woman experienced pain in her chest before being rushed to hospital and being diagnosed with blood clots in her lungs. Now a world-class triathlete, Zoe tells her story. This video may take a few moments to load.

(NPS Medicines Wise, Australia, 2013)

Video: Marina, Pulmonary Embolus at age 23

This video may take a few moments to load.

(Heart Foundation, Australia, 2016)

Pulmonary embolism(external link) Patient Info, UK

Pulmonary embolism(external link) Mayo Clinic, US

Cancer and thrombosis [PDF, 2.6 MB] Waitematā DHB, NZ, 2020

Preventing deep vein thrombosis [PDF, 933 KB] Waitematā DHB, NZ, 2020

Venous thrombosis [PDF, 196 KB] Waitematā DHB, 2020

References

- Acute pulmonary embolism(external link) ESC Clinical Practice Guidelines, 2014

Clinical guidelines

National policy framework – VTE prevention in adult hospitalised patients in NZ(external link) Health, Quality & Safety Commission, NZ

Surgical VTE prophylaxis guide(external link) Australian & NZ College of Surgeons

Venous thromboembolism guide – an overview(external link) NICE Guidelines, UK:

- Reducing venous thromboembolism risk in hospital patients(external link)

- Reducing venous thromboembolism risk – medical patients>(external link)

- Reducing venous thromboembolism risk – orthopaedic surgery(external link)

- Diagnosing venous thromboembolism in primary, secondary and tertiary care(external link)

- Treating venous thromboembolism(external link)

See our page Pulmonary rehabilitation for healthcare providers

Venous thromboembolism prevention project

Read about a project started in 2012 to prevent VTE at Counties Manukau DHB(external link)

Quality improvement initiatives

Reducing venous thromboembolism post op – orthopaedics team(external link) Counties Manukau Health

Brochures

Waitematā DHB, NZ, 2020

Waitematā DHB, 2020

Waitematā DHB, NZ, 2020

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust.

Reviewed by: Associate Professor Sue Wells, Public Health Physician, University of Auckland

Last reviewed:

Page last updated: