Antimicrobial resistance

Commonly called antibiotic resistance

Key points about antimicrobial resistance

- Antimicrobials include different groups of medicines that are used to prevent or treat infections caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites.

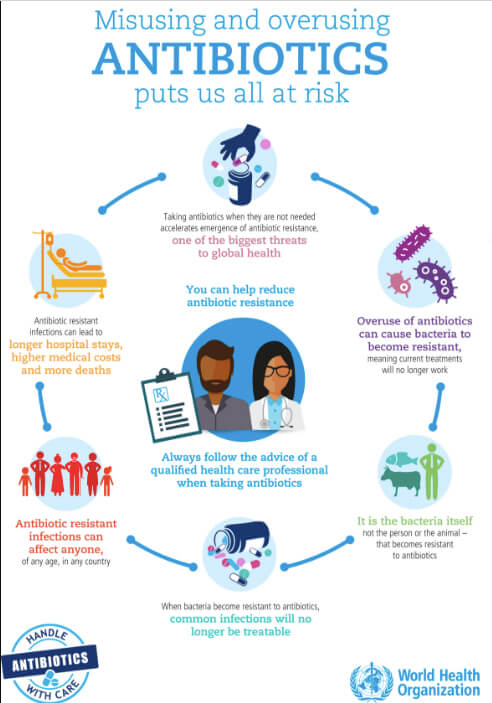

- Antimicrobial resistance happens when bacteria, viruses, fungi or parasites change so that antimicrobial medicines usually used to treat these infections no longer work.

- Antimicrobial resistance leads to higher medical costs, longer hospital stays and, sometimes, death.

- Preventing infection and using antimicrobials appropriately are key ways of fighting antimicrobial resistance.

Antimicrobial resistance occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites change over time and no longer respond to antimicrobial medicines. Infections become harder to treat and there is increasing risk of disease spreading, causing severe illness and death.

- Antimicrobial overuse increases the chance of some bacteria, viruses, fungi or parasites becoming resistant, which means when you next need antimicrobials they may no longer work to treat your infection.

- Resistant bacteria, viruses, fungi or parasites can multiply and spread to other people you have contact with, then these people can also develop antimicrobial-resistant infections.

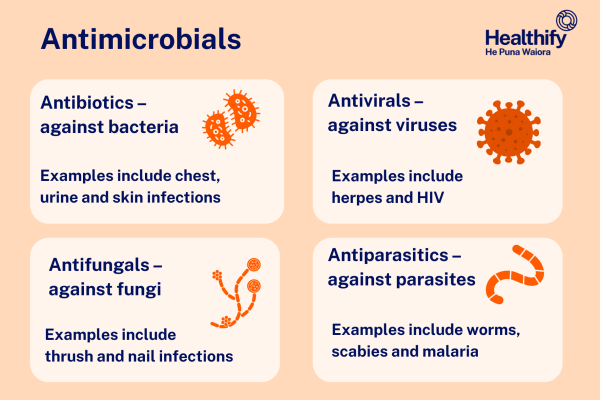

What are antimicrobial medicines?

Antimicrobials include different groups of medicines, eg, antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals and antiparasitics.

- They're used to prevent and treat infections in humans, animals and plants.

- Antimicrobials are lifesaving medicines, but only if they work against the organism causing infection.

- Antibiotics are the most commonly prescribed antimicrobial.

Image credit: Healthify He Puna Waiora

Why is antimicrobial resistance a concern?

Antimicrobial resistance is a major concern because it means some infections will become more difficult, and sometimes impossible, to treat.

Antimicrobial resistance is a concern because:

- it can lead to "harder to treat" or "untreatable'" infections

- it can lead to longer stays in hospital

- it can increase the risk of infection associated with surgery and other life-saving procedures

- there aren't many new antimicrobials being created to treat resistant germs/bugs.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the occurrence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is increasing. Examples of antibiotic-resistant bacteria include:

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) – a group of bacteria (called Staphylococcus aureus) that are resistant to commonly used penicillin-like antibiotics. Read more about MRSA.

- Extended spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) – chemicals produced by some bacteria that prevent certain antibiotics from working. Read more about ESBL.

- Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) – a group of bacteria (called enterococci) that are resistant to the antibiotic vancomycin. Read more about VRE.

Video: How can you prevent antimicrobial resistance?

(World Health Organization, 2021)

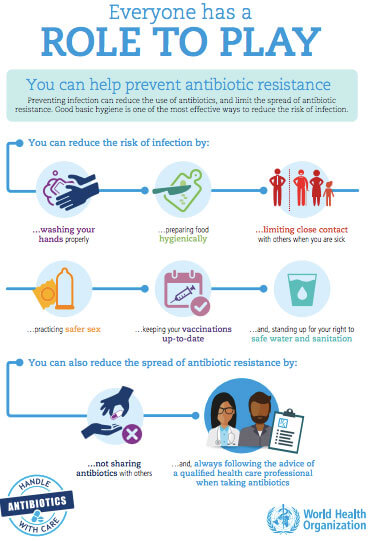

Avoid infection in the first place

Avoiding infections in the first place reduces the amount of antimicrobials that have to be used worldwide. This reduces the chance of antimicrobials developing resistance. Avoiding infections also prevents the spread of resistant antimicrobials.

Simple ways to avoid infections include washing your hands and getting vaccinated.

- Wash your hands regularly: Many infections can be avoided by washing your hands or, if that's not possible, using an alcohol-based hand gel. Wash your hands regularly, especially after using the toilet and before preparing food. Many bacteria are spread by person-to-person contact and can survive on surfaces, eg, doorknobs, desktops and benchtops. Read more about handwashing.

- Get vaccinated: Vaccination is a way of preventing certain infectious diseases (eg, mumps, measles, chickenpox and whooping cough). Vaccination uses your body’s natural defence mechanism (your immune system) to fight infections. If you've been vaccinated and you come into contact with that disease, your immune system will respond and prevent you developing the disease. Vaccination can reduce the chances of you getting sick, and the need for antibiotics. Read more about immunisation.

Use antimicrobials correctly

- Take the right dose, at the right time and for the right number of days (as recommended by your healthcare provider).

- Don’t use them if they haven't been prescribed for you.

- Only use antibiotics for an infection caused by bacteria. Antibiotics don't work against viruses, eg, a cold or the flu. Having green or yellow-coloured mucous, phlegm or snot isn’t a sign of a bacterial infection. Read more about snot and sputum.

Never share antimicrobials with others

The antimicrobials you are prescribed may not work for your family/whānau member, friend or neighbour’s illness. Using antimicrobials when they are not needed, or taking the wrong antimicrobials, can be harmful, and causes antimicrobial resistance.

Don't use antibiotics left over from a previous prescription

- The type, dose and amount of antibiotics left over may not be suitable to fight a new infection. Using the wrong type, dose and amount causes resistant bacteria to develop and multiply. Different infections may need different treatments, even though you might have similar symptoms.

- Leftover antibiotics may have expired, which means they may not work or may make you feel more ill. Liquid antibiotics often need to be kept in the fridge and expire quickly, and other antibiotics may not be labelled with a specific expiry date,

Dispose of antibiotics correctly

- If you have leftover antibiotics, return them to your pharmacy for safe disposal. Unused medicines taken to pharmacies are disposed of by specialist waste disposal companies.

- Don't put them down the toilet or sink because they may enter rivers, lakes and even drinking water supplies. In homes with septic tanks, antibiotics flushed down the toilet could seep into ground water or soil. Read more about medicines and the environment.

- Antibiotics that get into the environment may lead to bacteria becoming more resistant.

What is MRSA?

MRSA stands for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Staphylococcus aureus is a common bacteria – a type of germ or 'bug'. It's sometimes called 'Staph' for short. The bacteria usually live harmlessly on your skin and in your nostrils. Most people carry Staphylococcus aureus without knowing it as there are no symptoms.

- If these bacteria get into a wound or open cut, they can cause infections from boils on your skin to more severe infections of your bones, lungs and blood. These need treatment with antibiotics.

- MRSA is a type of Staphylococcus aureus which has developed a defence to commonly used penicillin-like antibiotics. It needs different antibiotics and can be more difficult to treat.

- MRSA is a concern in hospitals where there's a greater chance of bacteria entering your body from procedures, operations and drips (intravenous lines).

How do I know if I have MRSA?

When you are admitted to hospital a swab may be taken from your nose or any wounds that you may have. These are sent to the laboratory to find out whether you have MRSA.

What do I do if I have MRSA when I'm in hospital?

If you have MRSA during your stay in hospital, even if you don't have an infection, precautions will be taken to reduce the spread to other patients.

- You may be moved to a single room. You must wash your hands or use the alcohol hand gel provided before leaving your room and any wounds you have must be covered with a waterproof dressing.

- Hospital staff may wear gloves and gowns or aprons when caring for you.

- Your room may have a sign on the door so staff and visitors know that additional precautions are needed.

- Your room and the equipment used in your room will be cleaned and disinfected regularly.

- Everybody leaving the room must wash their hands or use the alcohol hand gel provided.

Other precautions

- Family and visitors: Family and friends including children and pregnant women can visit you but it's important that they wash their hands with soap and water or use an alcohol hand gel before leaving your room.

- Antibiotic treatment: If you have an infection caused by MRSA, only some antibiotics will work. They may need to be given as an injection into a vein.

- Future hospital admissions: You may be checked again for MRSA. Some people can have the bug for a long time.

What do I do if I get MRSA when I'm at home?

You can have MRSA in the community as well. You might get it from being in hospital or from someone else in the community who has it. It can be spread through direct skin to skin contact and by contaminated objects.

You’re more likely to get it if you have an underlying medical condition, have an open skin sore or wound, or have a tube entering your body (eg, a catheter or feeding tube).

If you have an MRSA infection or know you carry it on your skin:

- Follow the advice of your healthcare provider which may include taking antibiotics if you have an infection.

- It may be recommended that the MRSA be removed from your skin. This is known as decolonisation(external link).

- Cover any cuts, sores or wounds with a dressing or plaster.

- Tell your healthcare providers before they examine or treat you to help stop the spread.

If you know you have MRSA it’s important to take care with personal hygiene at home and in your workplace, kindy or school:

- Wash your hands well after using the toilet and before preparing food or eating

- Use separate towels to other whānau members

- Keep up with regular household cleaning.

Keep an eye out for any problems, such as wounds not healing, or signs that you may have a skin infection (pimples, boils, infected cuts or grazes).

What is ESBL?

ESBL stands for extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL). These are chemicals produced by some bacteria that prevent certain antibiotics from working. Bacteria that produce these chemicals are more resistant to antibiotics, making these infections more difficult to treat.

- ESBL-producing bacteria are commonly found in your bowel. They can live harmlessly without causing you to become ill. This is called colonisation doesn't need to be treated.

- Having ESBL-producing bacteria isn't a concern if you're fit and healthy.

- Sometimes, when your immune system is weakened, these bacteria can make you unwell with symptoms such as fever. Antibiotics are then needed to treat the infection, but antibiotic resistance from ESBL limits the types of antibiotic that can be used.

How do I know if I have ESBL?

People carrying ESBL in their bowel or other areas of their body show no symptoms and it's impossible to tell if a person has ESBL by looking at them. During your stay in hospital, if you have an infection, a swab or specimen of your blood, wound, urine or spit may be sent to the laboratory for testing.

What happens if I have ESBL?

If you're in hospital and have ESBL-producing bacteria, precautions will be taken to reduce the spread to other patients and staff.

- You may be moved to a single room and placed in contact isolation. If you're in contact isolation, it's important that you don't visit other patients. You may also be asked not to go into communal areas.

- You may have your own toilet.

- Hospital staff may wear gloves and gowns or aprons when caring for you.

- Your room may have a sign on the door so staff and visitors know that additional precautions are required.

- Your room and the equipment used in your room will be cleaned and disinfected regularly.

- Family and visitors: Family and friends including children and pregnant women can visit but it's important that they wash their hands with soap and water or use an alcohol hand gel before leaving your room.

- Future hospital admissions: You may be checked again for ESBL. Your body may clear the bacteria as you become well but that doesn't always happen.

Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) are a group of bacteria (called enterococci) that are resistant to the antibiotic vancomycin. Enterococci are bacteria that usually live harmlessly in your gut (intestines) without making you ill. This is called colonisation and doesn't need to be treated. Sometimes, in rare cases when your immune system is weakened, it can cause infection.

- Vancomycin is an antibiotic often used to treat infections caused by enterococci. When enterococci become resistant to vancomycin, it's no longer effective. This is called vancomycin-resistant enterococci or VRE.

- Most of the time VRE don't cause any problems and if you are colonised with VRE you don't look or feel different to anyone else. However, having VRE is of concern in hospitals where there's a greater chance of picking up bacteria and having a weakened immune system because of illness, medication or surgery. This puts you at risk of developing infections, and infections caused by VRE can be more difficult to treat.

How do I know if I have VRE?

People carrying VRE in their bowel or other areas of their body show no symptoms and it's impossible to tell if a person has VRE by looking at them. During your stay in hospital, if you have an infection, a swab or specimen of your blood, wound, urine or spit may be sent to the laboratory for testing.

What happens if I have VRE

If you to have VRE during your stay in hospital, even if you don't have an infection, precautions will be taken to reduce spreading it to other patients.

- You may be moved to a single room and placed in contact isolation. If you are in contact isolation, it's important that you don't visit other patients. You may also be asked not to go into communal areas.

- You may have your own toilet.

- Hospital staff may wear gloves and gowns or aprons when caring for you.

- Your room may have a sign on the door so staff and visitors know that additional precautions are required.

- Your room and the equipment used in the room will be cleaned and disinfected regularly.

- Everybody leaving your room must wash their hands or use alcohol hand gel.

Your family and antibiotics – what you need to know(external link) Pharmac, NZ

Antimicrobial resistance(external link) Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora

Drug infections are hard to treat(external link) (te reo Māori(external link)) Royal Society, Te Aparangi, NZ

Keeping antibiotics effective, with your help(external link) Canterbury District Health Board, NZ

Antibiotics can help, but they can also harm(external link) Canterbury District Health Board, NZ

Brochures

Your family & antibiotics – What you need to know(external link) PHARMAC, NZ

Antibiotic amnesty frequently asked questions(external link) Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand

5 questions to ask about your medications(external link) Health Quality and Safety Commission, NZ English(external link), te reo Māori(external link)

Think twice, seek advice(external link) World Health Organisation

Everyone has a role to play – you can help prevent antibiotic resistance [JPG, 284 KB] World Health Organisation

Misusing and overusing antibiotics puts us all at risk(external link) World Health Organisation

Keeping antibiotics effective, with your help(external link) Canterbury District Health Board, NZ

Antibiotics can help, but they can also harm(external link) Canterbury District Health Board, NZ

References

- Antimicrobial resistance – implications for New Zealanders(external link) Royal Society, Te Aparangi, NZ

- Antibiotic awareness week – a time to reflect on how we prescribe(external link) BPAC, NZ, 2017

- Antibiotic resistance questions and answers(external link) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US

- Keeping antibiotics working(external link) Pharmaceutical Society, NZ

- Infection prevention and control(external link) Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora, NZ

-

MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus)(external link) HealthInfo, NZ, 2022

Brochures

World Health Organisation, 2017

World Health Organisation, 2017

Antibiotics can help, but they can also harm

Canterbury District Health Board, NZ

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust.

Reviewed by: Angela Lambie, Pharmacist, Waitematā

Last reviewed:

Page last updated: