You can now add Healthify as a preferred source on Google. Click here to see us when you search Google.

Graves' disease

Key points about Graves' disease

- Graves’ disease is an autoimmune condition of the thyroid gland and is the most common cause of an overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism).

- You have a higher risk of developing Graves’ disease if thyroid problems or other autoimmune diseases run in your family, you are female or you smoke cigarettes.

- Graves’ disease is more common for Māori than non-Māori.

- Graves’ disease can be treated with antithyroid medicines, radioiodine or surgery.

- Most people with Graves’ disease respond well to antithyroid medicine.

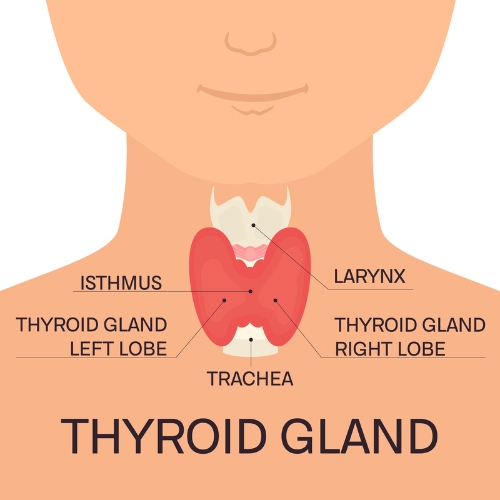

Graves’ disease is an autoimmune condition that affects your thyroid. Your thyroid is a small butterfly-shaped gland at the front of your neck below your Adams-apple that makes hormones. Thyroid hormones control your body’s metabolism (how you use energy), growth and other functions.

If you have Graves’ disease your body makes antibodies called thyroid stimulating immunoglobins (TSIs). These TSIs act like your natural thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and trick your thyroid gland into being overactive and making too much thyroid hormone (hyperthyroidism). Approximately 4 of every 5 cases of hyperthyroidism are caused by Graves’ disease.

TSIs can also affect your skin and eyes.

Image credit: Depositphotos

With Graves’ disease your body mistakes your thyroid as ‘foreign’ tissue, which causes your body to make TSI antibodies. It’s not clear why this happens but it’s known that your genes have a big impact on whether or not you’ll develop Graves’ disease.

Factors that can increase your risk of developing Graves’ disease

- Having thyroid problems or other autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes in your family.

- Smoking cigarettes.

- Being female.

- Having had surgery on your thyroid.

- Stress can also trigger Graves’ disease if you have the genes for the condition.

When you have Graves’ disease your thyroid is overactive (hyperthyroidism). When your thyroid is overactive it makes too much of the thyroid hormones T3 and T4 and these can cause many changes in your body. Your thyroid can grow to become a lump on the front of your neck (goitre) and people with Graves’ disease may also develop an eye disease called Graves’ ophthalmopathy or a skin condition called Graves’ dermopathy.

If you have Graves’ disease you may notice:

- feeling nervous or anxious

- feeling overly tired (fatigue) or poor sleep

- feeling hot or sweaty a lot of the time, or being unable handle the heat

- small trembling movements of your hands you can’t control (fine tremor)

- having to go to the toilet (poo) very often

- your heart beating fast (palpations)

- period changes – heavier or lighter periods, or periods that come more or less frequently

- muscle weakness or cramps

- skin, hair and nail changes

- weight loss

If Graves’ disease affects your eyes, you may also have:

- dry or gritty eyes

- red, irritated eyes

- swollen or puffy eyelids

- bulging eyes

- double vision

- a feeling of pressure behind your eyes

- constantly teary eyes

- sensitivity to light (photophobia).

Graves’ dermopathy, also known as pretibial myxoedema, is a rare skin condition that some people with Graves’ disease get. It involves the skin over your shins, calves or feet becoming thick, red and painful.

Video: Katie's story – hyperthyroidism

In the following video, Katie talks about the relief she felt when she found that the anxiety she’d been experiencing was caused by her overactive thyroid. She describes her journey through her teenage years and how she has successfully managed to get her symptoms under control allowing her to go on to study at university.

If your healthcare provider thinks you may have Grave’s disease, they will ask questions about your symptoms and your personal and family health history. They will do a physical exam to look for any signs of Graves’ disease.

Your healthcare provider will request blood tests to check your TSH and thyroid hormone levels, and may request additional tests such as antibody levels to help confirm a diagnosis of Graves’ disease.

If your healthcare provider finds you have a goitre when they examine you, they might also request an ultrasound and a biopsy of your goitre. An ultrasound involves scanning your goitre to look at its shape and size. A biopsy involves taking a small sample of thyroid tissue so the cells can be looked at under a microscope.

If Graves’ is confirmed, it’s also likely they will refer you to see an endocrinologist (a specialist hormone doctor).

There are 3 main types of treatment for Graves’ disease: medicines, radioiodine and surgery. Symptoms may not improve as soon as treatment is started, it can take a while for your body to regulate again. Talk with your healthcare provider if you are struggling despite following treatment advice.

Medicines

Carbimazole and Propylthiouracil (PTU) are 2 types of antithyroid medication that control thyroid hormone function. If you have Graves’ disease, you’ll stay on antithyroid medication for 12 to 18 months.

When medicines are stopped, 30 to 40% of people will continue to have normal thyroid function. The other 60 to 70% of people will get an overactive thyroid again. It’s hard to predict which group you’ll fall into, but if your thyroid becomes too active again it usually happens 1 year after stopping medication. If your thyroid becomes overactive again, you’ll notice your symptoms returning.

Propylthiouracil (PTU) is an antithyroid medicine that’s used if you have side effects from carbimazole or if you are, or plan to be, pregnant.

It's important to take your medicines everyday as forgetting will affect your blood test results and health. You will also need regular blood test monitoring while on these medications. It's important these tests are done as advised as it helps your healthcare provider make sure you're on the right treatment, at the right dose.

Side effects

A rare but serious side effect of these 2 medicines is sudden loss of white cells (neutrophils) in your blood. This makes you very vulnerable to infection. The first sign of this is a very sore throat, fever or other signs of infection for an unknown reason. If this happens to you, book an urgent appointment with your healthcare provider.

Beta-blockers such as propanol can be used to help control some of the symptoms of an overactive thyroid, such as palpitations.

Radioiodine

Radioiodine is a small dose of radioactivity given as an iodine tablet. It works by destroying some of the thyroid cells which stops them from making thyroid hormones. It takes 3 to 4 months for the treatment to have a full effect. 80 to 90% of people’s thyroid hormones become normal after a single dose. Read more about radioactive iodine therapy.

After having radioiodine treatment your risk of developing an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) increases. Your risk of hypothyroidism is also greater if you have a bigger dose of radioiodine. So lifelong yearly TSH blood tests are recommended if you have radioiodine to treat Graves’ disease. You may also need treatment for hypothyroidism.

Surgery

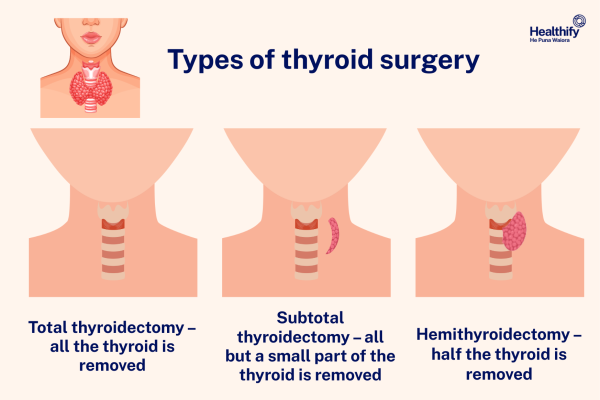

Surgery is an effective treatment option for Graves’ disease – especially if you have a large goitre which affects your breathing or swallowing. Surgery can involve removing all of your thyroid (a total thyroidectomy), taking most of it but leaving some there (subtotal thyroidectomy) or taking out half of it (hemithyroidectomy).

Image credit: Healthify He Puna Waiora

These are a few things you can do to cope with Graves’ disease and help your body heal:

- Get regular exercise – this can make you feel better by improving your muscle tone, heart and lung health and can also improve your energy levels.

- Learn relaxation techniques – stress can trigger Graves’ disease, so learning to relax and find a sense of calmness will be beneficial for your wellbeing.

- Avoid having too much iodine – avoid taking kelp supplements or eating seaweed products too often. Both are high in iodine and can make your overactive thyroid worse. Iodised salt, bread and seafood are still okay.

- Stop smoking cigarettes – smoking cigarettes is a key risk factor for developing Graves’ disease. Avoiding smoking will help improve your condition and be good for your overall health.

Apps reviewed by Healthify

You may find it useful to look at some mindfulness and meditation apps and quit smoking apps.

Most people with Graves’ disease respond well to antithyroid medicines. If you are symptom free and your thyroid blood tests are normal 1 year after treatment, you shouldn’t need further Graves’ disease check-ups, just occasional thyroid blood tests to make sure your thyroid levels are still normal.

After radioiodine treatment some people develop an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) and require long-term levothyroxine medication to treat this. Symptoms of an underactive thyroid include weight gain, feeling more cold than usual, dry skin and hair, less energy, pins and needles in your hands and a puffy face. You will also need more frequent blood tests after having radioiodine to monitor your thyroid hormones closely. Read more about hypothyroidism.

If you have Graves’ disease and you’re pregnant or planning to get pregnant, you should see your healthcare provider. You may need to change the type of antithyroid medication you are on and may need more frequent blood tests.

The NZ Thyroid Support Group(external link) provides support and resources to families and individuals who’ve been affected by thyroid disease.

The following links provide further information about Graves’ disease. Be aware that websites from other countries may have information that differs from New Zealand recommendations.

British Thyroid Foundation(external link) UK

Overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism)(external link) Healthinfo Canterbury, NZ

Hyperthyroidism (overactive), Graves’ disease and thyroid eye disease(external link) Australian Thyroid Foundation, Australia

Grave’s disease(external link) NHS University Hospitals Sussex, UK

Brochures

Thyroid gland – patient information(external link), Hawke’s Bay District Health Board, NZ, 2017

Your guide to hyperthyroidism(external link) British Thyroid Foundation, UK, 2018 also available in Mandarin(external link), Urdu(external link), Polish(external link)

References

- Thyroid disease – assessment and management(external link) NICE, UK, 2019 (updated 2023)

- Hyperthyroidism(external link) British Thyroid Foundation, UK, 2018

- Hyperthyroidism(external link) DermNet, NZ, 2016

- Graves’ disease(external link) Thyroid UK, UK, 2021

- Graves’ disease(external link) BMJ Best Practice, UK, 2025

- Overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism)(external link) Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora, NZ

Brochures

Thyroid gland – patient information

Hawke’s Bay District Health Board, NZ, 2017

Your guide to hyperthyroidism

British Thyroid Foundation, UK, 2018 Mandarin, Urdu, Polish

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust

Reviewed by: Dr Sara Jayne Pietersen, FRNZCGP, Auckland

Last reviewed: