You can now add Healthify as a preferred source on Google. Click here to see us when you search Google.

Epilepsy | Mate hukihuki

Key points about epilepsy

- Epilepsy (mate hukihuki) is a type of brain disorder where a person has recurrent seizures (sometimes called fits or convulsions).

- A seizure is a sudden burst of uncontrolled electrical and chemical activity in your brain.

- This disturbs its normal pattern of activity, causing strange sensations, emotions and behaviour or sometimes jerking or twitching of the body or limbs, muscle spasms and loss of consciousness.

- Epilepsy is common. About 1–2 in 100 people in New Zealand develop epilepsy at some stage in their life.

- Epilepsy often starts in early childhood. However, anybody at any age can develop epilepsy. Some people are born with epilepsy, while others develop it as children or adults.

- Most epilepsy is genetic meaning that it is due to changes in the DNA that directs brain cell function. Sometimes it can be due to damage to the brain cells such as after a head injury or illnesses such as a stroke.

- Epilepsy is not a type of mental illness or intellectual disability. Most kinds of epilepsy do not affect how well you think or learn but some may be associated with mental health disorders and cognitive and behavioural problems.

- There are many kinds of epilepsy. With treatment, most people with epilepsy live normal, full lives. Famous people who have had epilepsy include Julius Caesar, Thomas Edison and Handel.

- Regular contact with your doctor or nurse is important to help keep you well and seizure-free.

- If you have epilepsy, it’s important to learn about possible triggers such as lack of sleep, stress and drugs.

If you have epilepsy it means you experience recurrent seizures (sometimes called fits). A seizure is a sudden burst of uncontrolled or erratic electrical and chemical activity in your brain.

- Many people have a single seizure in their lifetime caused by injury, illness or fever. Having a seizure does not mean you have epilepsy.

- Epilepsy is diagnosed in individuals who have recurrent seizures or if they have only had a single seizure and have a high likelihood of having more.

- The frequency of seizures in people with epilepsy varies. For some people, there may be years between seizures. At the other extreme, some people have seizures every day. For others, the frequency of seizures is somewhere in between these extremes.

Most epilepsy is caused by genetic changes in the cells of the brain. When people have other family members with epilepsy this seems very obvious but many types of genetic epilepsy are not inherited (are not passed on from parents to child). The genetic change may only be in the person with epilepsy. Sometimes a person needs multiple genetic changes to develop epilepsy. Each individual genetic change may not cause epilepsy and can be inherited from either parent who does not have epilepsy. The combination of changes from both parents together combine to cause epilepsy. The abnormal bursts of electrical activity in the brain occur due to these genetic changes but we do not yet understand exactly why in many cases. It is unclear why seizures start at different ages or continue to occur.

Other causes of epilepsy include anything that injures the brain cells such as a head injury, a growth or tumour in your brain, a stroke and previous infections of your brain such as meningitis and encephalitis. Epilepsy can also be associated with other brain disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability or autism spectrum disorder. If you start getting seizures this will need to be fully investigated by your doctor.

Video: Epilepsy and the brain

Watch a video(external link) about the genetics underlying epilepsy, and epileptic seizures. It may take a few moments to load.

(Neurological Foundation of New Zealand, 2022)

Some people with epilepsy find that certain triggers make a seizure more likely, but often there is no obvious reason a seizure occurs at one time and not at another. These are not the cause of epilepsy but may trigger a seizure on some occasions.

| Possible triggers | |

|

|

The symptom of epilepsy is seizures. There are many different types of seizure, depending on the area of your brain that is affected. In general:

- Most people have a consistent pattern of seizures.

- Seizures can occur when you are awake or asleep.

People experience seizures differently:

- Some have episodes where they ‘go blank’ for a few seconds or minutes.

- Others remain fully conscious during a seizure and can describe their experience.

- For others, consciousness is affected and they are confused when the seizure ends.

The start of a seizure may involve the whole brain (generalised seizure) or part of the brain (focal seizure). In some types of seizures, individuals may lose consciousness and fall, with their limbs initially stiff and then jerking. This type of seizure is called a tonic-clonic seizure (previously known as grand mal).

Seizures are classified into 2 main categories – generalised and focal (which used to be called partial).

Generalised seizures

Generalised seizures result from abnormal brain activity on both sides of your brain at once. These seizures may cause momentary stares, loss of consciousness, falls or jerks of the body or limbs. There are 6 main types of generalised seizures.

Absence seizures

These used to be called petit mal. They are seen more often in children than adults. During an absence seizure you lose awareness of your surroundings. It is usually around 10 seconds long but can last as short as 5 seconds or very rarely up to 45 seconds. In some types of epilepsy absence seizures occur many times per day. The person will seem to stare vacantly into space, stop talking mid-sentence or stop walking. Some people will flutter their eyes or smack their lips. The person will have no warning that a seizure is about to start and after the seizure will have no memory of it. These seizures can be dangerous if they occur at a critical time, such as riding a bike, driving or crossing a street.

Myoclonic seizures

These types of seizures cause your arms, legs or upper body to jerk or twitch as if you have received an electric shock. They often only last for a fraction of a second, and you will remain conscious during this time. Myoclonic seizures are very similar to the jerks people have when they are falling off to sleep but the myoclonic seizures occur when a person is awake. Jerks during sleep are normal and not myoclonic seizures.

Clonic seizures

In a generalized clonic seizure a person has rhythmic jerking of their limbs and body. These seizures usually last less than 5 minutes. A person is not aware of their environment when they are having a generalized clonic seizure. After the seizure is finished the person is often confused and sleepy.

Atonic seizures

These cause all your muscles to suddenly relax. This means you may fall to the ground and be injured.

Tonic seizures

These seizures cause all your muscles to suddenly become stiff, which can mean you lose balance and fall over. Like atonic seizures, there is a risk of you getting injured.

Generalised tonic-clonic seizures

Tonic-clonic seizures are also called convulsions and used to be known as grand-mal seizures. They have two stages. First, your body and limbs becomes stiff and then your limbs and body have rhythmic jerking or twitching. You lose consciousness and some people will wet themselves because the abnormal brain activity interferes with bladder control. The seizure normally lasts less than 5 minutes. These seizures have no warning (or aura) that they are coming. After the seizure, a person can be confused for a short period followed by tiredness and often sleep

Focal seizures (used to be called partial seizures)

Focal seizures result from abnormal brain activity starting in one part of one side of the brain. The sensations or feelings you experience during a focal seizure depend on which part of your brain is affected. Focal seizures may spread to other areas in the brain on that side or even further to involve both sides of your brain.

Focal seizures are classified into types based on what happens during a seizure.

Focal aware seizures

In focal aware seizures, you do not lose consciousness or awareness. During the whole event you are completely aware of everything that is going on around you. You may have muscular jerks or strange sensations in one arm or leg, or feelings or sensations. Examples of these include:

- a general strange feeling that is hard to describe

- a ‘rising’ feeling in your tummy – like the sensation in your stomach when on a fairground ride

- an intense feeling that events have happened before (déjà vu)

- experiencing an unusual smell or taste

- unusual visions such as coloured blobs

- a tingling sensation, or ‘pins and needles’ in your arms and legs

- a sudden intense feeling of fear or joy

- stiffness or twitching in part of your body, such as one side of your face, an arm or hand.

If these seizures spread they may progress to the types below. In a seizure that spreads the focal aware part of the seizure is sometimes called an aura because it can give warning that a larger seizure is coming. This can give you time to warn people around you and make sure you are in a safe place.

Focal impaired awareness seizures

These seizures may start like a focal aware seizure but then you lose awareness of what is going on around you, cannot respond normally to other people and can’t remember what happened after the seizure has passed. Symptoms can include random movements or actions such as:

- smacking your lips

- rubbing your hands

- making random noises

- adopting an unusual posture.

Focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures

A seizure may start like a focal aware seizure or a focal impaired awareness seizure but then progress to involve both sides of the brain. This means that you may become stiff all over for a brief period of time before having rhythmic jerking or twitching of your body and/or limbs. During the stiffness and jerking you are unaware of what is happening. These seizures usually last less than 5 minutes but can take a lot out of you leaving you confused and drowsy afterward sometimes for 30 minutes or more.

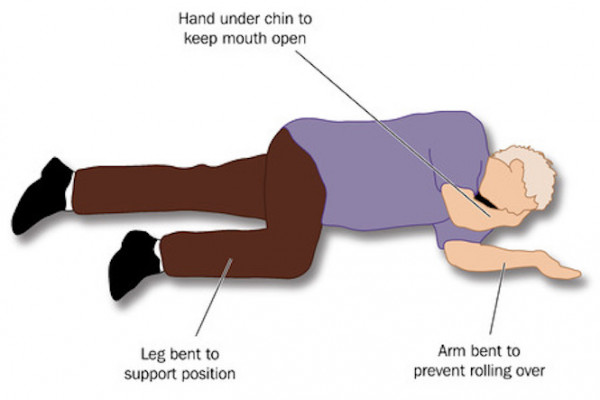

Having the right assistance and support during a seizure can help prevent people from sustaining serious injuries.

Some types of seizure require little more than reassurance. However, if a person has a seizure that causes them to fall down, convulse (where their muscles relax and tighten rhythmically causing the body and limbs to jerk), breathe noisily and with difficulty and lose consciousness, first aid and careful observation are required.

Do

- Stay with the person until the seizure ends.

- Protect the person from injury, such as by clearing the area, removing sharp or hard objects and moving them if they are in a dangerous place. If the person is close to a wall or hard furniture, pad the area with clothing or a pillow to avoid further injury.

- Time the seizure.

- When the seizure has stopped, turn the unconscious person onto their side (into the recovery position) to keep their airway clear. Read more about recovery position.

- Cover the person lightly with a coat or blanket.

- Speak calmly to the person and reassure them, even if you are not sure that they can hear you.

- See if the person has a medical alert bracelet or pendant. This may provide useful information.

Image credit: 123rf

Don’t

- Put anything in the person’s mouth or force anything between their teeth (the tongue cannot be swallowed).

- Hold the person down. This may result in a broken bone or soft tissue injury.

- Give the person water, pills or food until they are fully alert.

When should you call an ambulance?

It's not usually necessary to call an ambulance when a person has an epileptic seizure, but an ambulance should be called when:

- the seizures last for more than 5 minutes

- a second seizure occurs without the person regaining consciousness

- the person does not wake up within 10 minutes after the seizure

- the person has injuries that require medical treatment

- the seizure happens when the person is in water

- vomiting occurs during the seizure.

The most important tool for diagnosing epilepsy is your history. Your doctor will want to know what happened, whether anyone else saw you, whether there were any triggers, how you felt afterwards, if you had any previous symptoms or any family history of epilepsy, any infections, your birth history and so on.

It is extremely helpful for your doctor to see videos of your seizures. If at all possible it is great to give your permission for other family members or friends to video you having a seizure on their phone so that you can show this to your doctor. Any possible seizure-like symptoms need to be discussed with your doctor right away. You must not drive until a doctor says it is safe for you to drive again.

Some of the tests that are used to help diagnose epilepsy are:

- EEG – an electroencephalogram (EEG) is a test to measure the electrical activity of the brain.

- brain scans such as magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography.

You may be asked to have a Sleep Deprived EEG, where you attend your appointment when you are short of sleep. While there are no direct side effects from the EEG itself, you should be very careful until you have had a chance to sleep properly as lack of sleep can make seizures more likely. Don't drive on the day of the test, and it is advisable that someone stays with you for the rest of the day until you have had a chance to sleep properly.

The most common treatment for epilepsy is medication, called anti-seizure medication (ASM). While ASMs do not cure epilepsy, many people have their seizures successfully controlled with anti-seizure medication.

Anti-seizure medications (ASMs)

These work by stabilising the electrical activity of your brain, and successfully control seizures for many people. There are several different ASMs available. Your health professional can talk to you about the best medication for you. Deciding on which medicine to prescribe depends on many things such as:

- your type of epilepsy

- your age

- other conditions you have

- other medicines that you may take for other conditions, and their possible side-effects

- whether you are pregnant – read more about epilepsy and pregnancy

- whether you are planning a pregnancy – read more about epilepsy and contraception.

It may take some time to find the medication that works best for you. In most cases, only one ASM is needed to prevent seizures, but some people may need 2 or more. When starting your ASM, your doctor will start you on a lower dose and may increase it if this fails to prevent seizures.

The decision about when to start medication can be difficult. A first seizure may not mean that you will have a second seizure and a second seizure may not occur for years later. The decision to start medication should be made by thinking about the benefits and risks of starting, or not starting, the medicine. In children, it is unusual to start treatment after a first seizure. A common option is to wait and see after a first seizure. If you have a second seizure within a few months, more are likely, so it may be a good idea to think about starting medication.

Read more about anti-seizure medication and how medicines for epilepsy, mental health and pain can harm your unborn baby.(external link)

Other treatments for epilepsy

- Surgery to remove the cause of seizures in your brain is an option in a small number of individuals with focal epilepsy. It may be considered when medication fails to prevent seizures. It is only possible for certain causes in certain areas of the brain, so, only a small number of people are suitable for surgery. Also, there is risk involved in brain surgery. However, techniques continue to improve and surgery may become an option for more people in the future.

- The ketogenic diet, which needs to be supervised by an experienced dietitian, is useful for some children and adults with particular types of epilepsy that will not respond to medication. Read more about ketogenic dietary therapies(external link).

- Complementary therapies, such as aromatherapy, may help with relaxation and relieve stress but have no proven effect on preventing seizures.

Healthy eating, regular exercise, being a non-smoker, taking your medications correctly, having a positive attitude and seeing your healthcare team regularly, are all very important steps you have control over for keeping well. Here are a few tips on what you can do to live well with epilepsy.

| Tip | Description |

|---|---|

| Know your triggers | Some people can identify certain events, lights, stress or foods that can trigger a seizure. Keeping a diary can be a good way to help work out what these may be for you. |

| Take your medication | Take your medication exactly as prescribed. If you have any questions or are unsure of what to take and when check with your pharmacist or doctor. This is probably the most effective way to live well with epilepsy. Missing out doses of medication increases the risk of more seizures. |

| Regular reviews with your GP/nurse team | Regular reviews of your epilepsy and treatment with your GP/nurse team are very important to help pick up problems early and prevent other problems arising. Often people with epilepsy are also under a hospital specialist team (neurologist or clinical nurse specialist) when expert input is needed. |

| Eat a balanced diet | Eat a balanced diet, containing all the food groups, to give your body the nutrition it needs. |

| Exercise regularly | Exercising regularly can increase the strength of your bones, relieve stress and reduce fatigue, which can reduce the likelihood of seizures. Read more about epilepsy, sports and leisure(external link). |

| Limit alcohol | Heavy drinking can cause seizures, as well as interact with your medication, making side effects worse and the medication less effective. Heavy drinking also upsets sleep patterns and this can increase your chances of having a seizure. |

| Create a safe environment | Be aware of how to reduce injuries and accidents caused by seizures. Read more about safety around the home(external link). |

| Become an expert self-manager | Become an expert self-manager. You are the most important person to keep yourself well and your epilepsy well controlled. Self-care involves taking responsibility for your health and wellbeing with support from those involved in your care. Also, talk to your healthcare provider about any aspect of your care that you are not satisfied with. Together you can find support and solutions. Read more about how to communicate with health professionals(external link). |

People with long-term conditions such as epilepsy can benefit enormously from being supported to self-care. They can live longer, experience less pain, anxiety, depression and fatigue, have a better quality of life and be more active and independent.

If you want to find out more about epilepsy self-management, you may want to talk to your GP or specialist about participating in a self-management programme.

Apps reviewed by Healthify

You may find it useful to look at some Epilepsy apps that can help you keep track of your seizures and medication.

If a person with epilepsy dies and no other cause of death can be found, this is called SUDEP (sudden unexpected death in epilepsy).

How common is SUDEP?

SUDEP is less common in children than in adults.

- In one year, SUDEP typically affects about 1 in 1,000 adults with epilepsy; in other words, 999 of 1000 adults will not be affected by SUDEP

- In one year, SUDEP typically affects about 1 in 4,500 children with epilepsy; in other words, 4499 of 4500 children will not be affected by SUDEP.

Who is at risk of SUDEP?

The cause of SUDEP is unknown but there are some things that can increase the risk of SUDEP:

- having tonic-clonic seizures (previously call grand-mal seizures)

- having seizures at night or seizures when asleep

- having poorly controlled epilepsy, usually because of not taking medication regularly as prescribed.

Can I change the risk of SUDEP?

The best way to lower your risk of SUDEP is to minimise the number of seizures you have. See the information above about what self-care can I do if I have epilepsy?

Read and listen to stories of people living well with epilepsy.

Epilepsy and my son – Laura Collins

As a parent you pray that you will never have to watch your children suffer will illness, disease or any medical condition that will impair their lives so when my 10-year-old son, Ben, was diagnosed with epilepsy last year it was a huge blow for the whole family. Understanding how to manage the condition (and teaching him to manage it too) has been a big – and often difficult – learning curve but we are getting there one day at a time and Ben is coping admirably. Myself, my husband and his younger brother are doing everything we can to support him following his relatively recent diagnosis but it's not always easy. This is our story.

In the beginning

Although Ben didn't have what many people consider to be a 'traditional' epileptic seizure until last year I always had a feeling that something wasn't quite right. As a young child he would often stare vacantly into space, sometimes smacking his lips, fluttering his eyes and making strange noises. I'd ask him what he was thinking and he wouldn't respond then afterwards he had no memory of his temporary 'zone out' as his father and I called it. Doctors put it down to his age and suggested he had a low attention span. At this stage epilepsy never crossed my mind and I had no idea that his odd behaviour was actually him suffering from complex partial seizures where the neurons in his brain were erratically firing off electrical impulses.

The fit

The day that Ben had his first 'tonic-clonic seizure' was probably the most terrifying of my life. I was home alone with Ben and his younger brother Thomas and I was trying to do some chores while they played on their computer games console. Suddenly without warning, Ben lost consciousness, became stiff and then started violently shaking and convulsing on the floor. I had no idea what was going on and felt utterly powerless. Screaming at Thomas to call an ambulance, all I could do was hold my precious boy and pray that he would be okay. Thankfully after about two minutes (incidentally the longest two minutes of my life) Ben regained consciousness and, other than being utterly mortified that he'd wet himself during the seizure, he seemed fine. He was taken to hospital where neurological doctors ran EEG tests before making the epilepsy diagnosis. I remember feeling an huge wave of relief. I didn't know much about the condition but I knew that it was manageable and after fearing for my son's life only a few hours before I felt sure that this had to be a more positive outcome.

Moving forward

Ben's epilepsy is controlled by medication (or rather the medication reduces the likelihood of him having seizures) and we are working together with Ben to implement a daily routine of taking it and also to try and identify the triggers that tend to lead to his fits. In the 18 months since his first tonic-clonic fit he has had two more and both of these occurred when he was over-tired so keeping him in a good sleep routine is essential. I don't think I will ever get used to the sight of him having a seizure – it is extremely upsetting – but we know how to react now and trying not to move him, removing any harmful objects nearby, cushioning his head and simply comforting him until the fit subsides usually helps us feel like we are regaining a little control over the situation.

Unfortunately Ben's diagnosis came when he was at a difficult age. He is old enough to know that he has a lifelong condition and thanks to a lot of the wonderful educational resources aimed at children with epilepsy he now knows a lot about the science behind his condition. However he is still young enough to feel sensitive about the injustice of the situation and the phrases 'It's not fair' and 'why me?' are uttered a lot in our home, particularly when he is unable to do things that his brother and friends are doing. I noticed that his self esteem suffered and have worked hard to try and build him back up again through positive reinforcement, responsibilities and good, old fashioned motherly love.

Everyone's experience of living with epilepsy is different and of course I pray that with the help of his medication and the support of his family, Ben will be able to live a life that is not impaired by his condition.

While epilepsy cannot be cured, most people who have it live full, normal and happy lives. However, epilepsy can be difficult and frustrating if you cannot drive or do your favourite activities or sports.

- Contact Epilepsy NZ(external link) 0800 37 45 37 (Epilepsy NZ) and online support groups to talk with families who know what it's like.

- Make sure children are supported and not getting teased or bullied at school.

- Look out for emotional or behavioural problems especially in children which can be more common in those with epilepsy.

- In New Zealand there are numerous social supports available through social services.

Epilepsy FAQ(external link) Epilepsy NZ

Epilepsy and newborn babies(external link) Epilepsy NZ

Epilepsy and children(external link) Epilepsy NZ

Epilepsy and women(external link) Epilepsy NZ

Epilepsy and men(external link) Epilepsy NZ

Epilepsy and memory(external link) Epilepsy NZ

Medicines for epilepsy, mental health and pain can harm your unborn baby(external link) (For women and their families/whanau) ACC NZ

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy(external link) Brain Health Research Centre, University of Otago

SUDEP(external link) Epilepsy Foundation, US

SUDEP(external link) Epilepsy Society, UK

Living with epilepsy(external link) NHS, UK

Apps

Resources

Epilepsy & head injury(external link) Epilepsy Association of New Zealand

Medicines for epilepsy, mental health and pain can harm your unborn baby(external link) ACC, NZ, 2020

First aid for seizures(external link) Epilepsy NZ

First aid for seizures (wheel chair)(external link) Epilepsy NZ

Ketogenic dietary therapies(external link) Epilepsy NZ, 2016

References

- Epilepsy(external link) Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora

- Epilepsy guidelines and pathways for children and young people(external link)(external link)Starship, NZ 2022

- What is epilepsy?(external link)(external link) Epilepsy Society, UK

- Epilepsy(external link)(external link) Better Health Channel, Australia

See our pages Epilepsy for healthcare providers and Long-term conditions for healthcare providers.

Apps

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust.

Reviewed by: Professor Lynette Sadleir, Paediatric Neurologist, University of Otago, Wellington

Last reviewed:

Page last updated: