Side effects of chemotherapy

Key points about chemotherapy side effects

- The side effects you might experience from chemotherapy depend on the medicines you receive and how they affect you.

- Chemotherapy mainly affects parts of the body where normal cells rapidly divide and grow.

- These include the lining of the mouth, skin and hair, the digestive system, the testes and the bone marrow (where blood cells are produced).

Most chemotherapy side effects are short lived and go away within a few days or weeks. However, some side effects are permanent. Ask your specialist or oncology nurse what to expect, what symptoms you should report right away and whether you are likely to have any permanent effects.

- You are unlikely to experience all of the possible side effects, but tell your doctor or nurse about any effects you do get, as they need to know how you are coping with the chemotherapy.

- They may be able to help control the side effects, or they may want to change your treatment to try to avoid them.

White blood cells, produced in the bone, are essential for fighting infections. Chemotherapy reduces the amount of white cells produced, making it difficult for you to fight off infections.

What can you do?

You should be given written information from your healthcare team about what to watch for. Your list may differ slightly from this.

| Call your cancer doctor or nurse if you get the following: |

Don't ‘wait to see what happens’. Follow the advice of your medical team. You may need to go to hospital for a thorough check-up or intravenous (IV) antibiotics. |

How to protect yourself against infection during chemotherapy

- Look after your body – brush your teeth twice a day, use alcohol based hand sanitiser regularly, shower or bathe every day, keep any cuts or scrapes clean.

- Keep away from germs – keep away from people who have illnesses you can catch, e.g. cold, flu or chickenpox, try to stay away from crowds, wash or peel fruit and vegetables before you eat them, don’t eat raw fish, seafood, meat or eggs.

- Medicines – ask your doctor, nurse or pharmacist before taking any medicines. Some medicines can hide the signs of infection. These include paracetamol, aspirin and ibuprofen.

- Vaccinations – ask your doctor, nurse or pharmacist before you have any vaccinations.

- Pets and other animals – can carry infections. Wash your hands after touching pets or other animals. If possible, don’t clean up poo from cats, dogs or other animals, or clean out fish tanks, bird cages or cat litter trays.

Myths about fever

Be careful not to believe these myths about fever.;

-

‘Fevers come and go – it’s best just to let them run their course.’

FALSE.

Fevers are always an indication that something is wrong, and should be treated and reported. If they get too high, they can lead to dehydration and seizures. When someone is undergoing chemotherapy or radiation treatment, fevers often indicate infection, which is serious and requires medical attention. -

‘Fevers help burn up whatever is wrong.’

FALSE.

High fevers do not destroy bacteria that cause infection. This is why your doctor or healthcare team will treat both the fever and the possible infection – if your white blood cell count is low, your body will not be able to fight off the infection on its own.

Read more about cancer, infection and sepsis.(external link)

Red blood cells are produced by the bone marrow and carry oxygen around the body. Chemotherapy may reduce the amount of red cells produced, making you feel tired, low in energy, dizzy, light-headed, and breathless.

What can you do?

- Let your cancer doctor or nurse know if you feel tired, low in energy, dizzy, light-headed, and breathless.

- Conserve your energy where you can – rest adequately, and eat a balanced diet.

Platelets are produced by the bone and help the blood to clot and prevent bleeding. Chemotherapy can lower the number of platelets, which increases your risk of bleeding, and you may bruise easily.

What can you do?

- Be careful when using sharp objects like a knife, scissors, razor.

- To prevent bleeding gums, use a soft toothbrush and brush gently.

- Apply gentle but firm pressure to any cuts you get until the bleeding stops.

- Contact your cancer doctor or nurse immediately if you have any unexplained bleeding or bruising (eg, a bleeding nose that won’t stop or blood in your urine or bowel motions). You may need a platelet transfusion.

Fatigue, or tiredness is a very common side effect of chemotherapy. It can be caused by a number of factors such as the chemotherapy itself, poor appetite, not sleeping well, dehydration or anaemia.

What can you do?

- If you do get tired, try to take things easier. Only do as much as you feel comfortable doing.

- Try to plan rest times in your day.

- Also try to ensure you are drinking plenty of fluids, eating well and having some form of gentle physical activity. This will help you cope better with the treatment.

- Don't be afraid to ask for some help. Family, whānau, friends and neighbours may be happy to have the chance to help you – tell them how they can help.

- If you're not sleeping well, tell your doctor or nurse. They may be able to suggest ways to help, or prescribe sleeping tablets or a mild relaxant.

- Watch this video by Dr Mike Evans about fatigue and cancer.

Some types of chemotherapy can cause nausea (feeling sick like you want to vomit), vomiting, or both. Depending on the type of chemotherapy, these feelings can occur while you are getting chemotherapy, right after, or many hours or days later.

Not everyone feels sick after chemotherapy and anti-sickness medicine has greatly improved over the past decade.

What can you do?

- Anti-sickness medicines are frequently given to prevent sickness occurring. It is important to take your medicine for nausea exactly as prescribed. Check with your doctor or nurse if you can drive while you are taking these medicines.

- If nausea (feeling sick) or vomiting (being sick) persists longer than 24 hours, contact your oncology nurse or doctor.

- If you feel sick, try some of these ideas:

- If you feel sick before treatments, eat lightly before each treatment.

- Eat smaller amounts more often.

- Eat slowly and chew well to help you digest your food better.

- Eat your main meal at the time of the day when you feel best.

- Try not to eat fatty things.

- Eat dry toast or crackers – they often help.

- Drink clear, cool and unsweetened drinks like apple juice.

- Don't do anything too strenuous after a meal, but try not to lie down for at least 2 hours after a meal.

- Try breathing deeply through your mouth whenever you feel like being sick.

- If cooking or cooking smells make you feel sick, ask others to cook for you, or prepare meals between treatments and freeze them.

- Ask the nurse or hospital social worker where you can learn relaxation or meditation methods.

You may have no problems with your appetite during treatment, or you may not feel like eating at all. Changes to your appetite can be because of your treatment, your cancer or just because of the whole experience of having cancer and being treated for it.

Your sense of taste may change. This change can last for the duration of chemotherapy but will then return to normal once chemotherapy stops.

What can you do?

- Try different foods until you find foods that you enjoy.

- Eat smaller amounts more often, or try drinking special liquid supplement foods you can get from your pharmacist.

- Even when you're not able to eat very much, it's important to drink plenty of clear fluids.

- Your hospital may have its own diet information for cancer patients. You can also talk to the hospital or community dietitian for advice about what to eat.

Some people gain weight during chemotherapy. Talk to a dietitian if this becomes a problem for you. Any weight gained during chemotherapy can be due to medicines, but usually comes off when treatment stops.

Loosing your hair during chemotherapy, depends on the type of chemotherapy given. Ask your specialist what to expect based on your treatment plan. Your hair may start to fall out 2–3 weeks after the first treatment or it may not fall out for quite a while. Your scalp may feel hot or itchy just before it starts to fall out.

What can you do?

- You might want to wear a hairnet at night to catch all the hairs, or use a mini vacuum to clean the hairs from your pillow.

- Many people find losing their head hair very upsetting. Try to remember that it will grow back. Until it does, you might want to wear a wig. It's a good idea to get a wig fitted before you start losing your hair, so that it matches as closely as possible your style and colour. You may want to get your hair cut shorter so that it fits better under a wig. Spend some time choosing one that suits you.

- The Government helps pay the cost of a wig. You must get a certificate from your doctor that states you are entitled to a wig. Some people don't bother with a wig. They stay bald or cover up with a scarf or hat.

- Your hair will grow back again when your treatment stops. It takes between 4 and 12 months to grow back a full head of hair. It is possible your new hair may be a different texture or colour. Your scalp may be quite itchy as your hair grows back. Frequent shampooing can help.

- There is no medical reason why you have to cover up your head. However, your scalp will be more sensitive to the sun than normal, so you should wear a hat or a high protection sunscreen (SPF 30+) on your scalp when you are in the sun. In the winter your head may feel much colder than it normally would.

The cells that make up the lining of your mouth replace themselves very frequently. Chemotherapy affects these cells, and can lead to a sore mouth or mouth ulcers.

What can you do?

- It is important to keep your teeth, gums and mouth very clean during your treatment to help stop infections. The nurses can show you how to do this. Use a very soft toothbrush or a cotton bud for your teeth and gums, and avoid vigorous or rough brushing.

- Use a mouthwash regularly. Don't use a commercial one (readymade or bought) because they can be too drying and make your mouth more painful. Ask your doctor or nurse for advice or you can make one yourself by mixing 1 tsp of salt and 1 tsp of baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) in 4 cups of warm water. Use it 3 times a day after meals or as often as you need to. Your specialist may give you a special liquid mouthwash.

- Eat soft foods and have lots to drink. Avoid foods with a high acid level such as grapefruit, tomatoes or oranges and avoid spicy foods and spirits.

- Use a lip balm or ointment on your lips if they are dry.

- If your mouth or throat is dry and you have trouble swallowing, try some of these ideas:

- suck on ice blocks

- drink lots of liquids

- moisten foods with butter

- dunk dry biscuits in tea

- blend foods and eat soups and ice creams

- ask your dentist, doctor or nurse about artificial saliva

- don't smoke.

- If your mouth is very sore or if you get ulcers or thrush (a white coating in the mouth), see your doctor or nurse straightaway for advice on treatment.

Chemotherapy may cause your skin to become red, peel or get dry and itchy. You might also get drying and cracking of the fingers around the nails. Your nails may become coloured, brittle and ridged. You may get some acne.

What can you do?

- Use a lotion or cream to stop the dryness. Apply it while your skin is still damp after washing.

- Avoid perfumes, cologne, or aftershave lotion that could irritate the skin.

- Avoid long, hot showers that can dry the skin. Have short, cool showers or sponge baths.

- It is especially important to cover up your skin and use a high protection sunscreen (SPF 30+) in the sun when having chemotherapy.

- Your skin may go red or thicken where the injection or the drip goes in. If this happens, tell your doctor or nurse immediately.

- Tell your doctor about any skin problems.

Diarrhoea is frequent bowel movements that may be soft, loose or watery.

Chemotherapy can cause diarrhoea because it affects the healthy cells lining the large or small bowel. It can also speed up your bowels.

What can you do?

- Eat small frequent meals.

- Drink clear fluids between meals to replace lost fluids.

- Avoid seeds, pips and skins in fruit, vegetables and grains.

- Avoid spicy foods, greasy foods and foods that cause gas such as beans, cabbage, broccoli.

- Avoid cow's milk. Lactose in milk (milk sugar) can cause cramping pains and diarrhoea.

- Mild cheese and yoghurt are low in lactose and can be eaten.

- Let your doctor know if your diarrhoea lasts longer than 24 hours or if you have pain, cramping or bleeding with diarrhoea.

Constipation is when bowel movements become less frequent and stools are hard, dry and difficult to pass. You may also get stomach cramps, gas in the tummy, or pain in the rectum (lower bowel).

Chemotherapy and pain medicines such as opioids can cause constipation. Other factors that may make constipation worse are poor appetite and eating less, dehydration, and spending a lot of time sitting or lying down.

What can you do?

- Drink at least 6 to 8 cups of fluid (1500 ml) each day, and keep yourself well hydrated.

- Eat regular meals. Don't miss breakfast.

- Add extra fibre to your food, eg, add wheat-bran flakes to your breakfast cereal or use them in cooking.

- If you think the constipation has been caused by the anti-nausea or pain medicines, it's likely you’ve been given a laxative to take as well. Try to take this ahead of time to avoid getting to the point of constipation.

For some people, having cancer and treatment for it has no effect on their sexuality and sex lives. For others, it can have a profound impact, affecting how they feel about themselves, their attractiveness, and their sexual desire. Dealing with any changes is an ongoing process of adjustment.

The side effects of chemotherapy may mean that you don't feel like having sex because you feel tired, nauseous or unattractive, or you're struggling with your body image or in pain. It is important to keep communication open with your partner – for both of you to share your fears and needs.

Sexual intercourse is only one of the ways you can express affection for each other. Gestures of affection, gentle touches, cuddling, and fondling can also foster intimacy and closeness.

Women

- Woman may find their periods become less regular or stop altogether.

- They may get hot flushes or other symptoms of menopause, and an itchy, burning or dry vagina.

- Women may also get vaginal infections, such as thrush.

- Ask your doctor or nurse for something to help if you have any of these problems.

Men

- During treatment some men may have difficulties achieving or maintaining an erection, though others will be fine.

- For most men their usual sex drive and fertility return some time after treatment is over.

- Talk to someone you trust if you are experiencing ongoing problems with sexual relationships. Friends, nurses, or your doctor may be able to help.

Sexual orientation and gender identity can have a significant impact on the well-being of those with cancer. Discrimination and systemic barriers to care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer or Questioning, Intersex or Asexual (LGBTQIA+) individuals can add to the stress of coping with a cancer diagnosis. There are ways to advocate for yourself and find the care you need and deserve.

Additionally, a transgender person might retain aspects of their biological sex that require certain forms of care. A trans man may need care from a gynaecologist or continued breast exams. A trans woman may require care from a proctologist. Many health care systems still rely on male-female binaries, potentially making non-binary or gender nonconforming patients feel invisible. If you face discrimination, don't be afraid to seek a second opinion or a better fit.

One of the benefits of coming out to your provider is that you can be honest about your support network. These individuals can then be included in the overall plan of care. From a coping perspective, a sense of being recognized and accepted can enhance feelings of trust.

Unfortunately chemotherapy carries the risk that you may become infertile, either temporarily or permanently. However, contraception should be used if a woman has not gone through menopause, because there is a slight risk of miscarriage or birth defects for children conceived during treatment. Talk to your doctor about this before you start treatment.

What can you do?

- Talk to your team about methods of fertility preservation, should this be something you wish to do.

- It's usually recommended that contraception is used for at least 12 months after chemotherapy is completed.

- If you are pregnant now, talk to your doctors about it straight away.

If at any time you are concerned about the side effects or experiences you are having during chemotherapy, please speak to your treating team.

Chemotherapy side effects(external link) American Cancer Society

Patient information sheets(external link) eviQ, Australia

Coping with cancer as an LGBTQIA+ person(external link) Cancer Care, US

Fertility preservation(external link) Fertility Associates, NZ

For healthcare providers

Managing long term side effects of chemotherapy(external link) BMJ visual summary, UK, 2016 Chinese(external link)

Resources

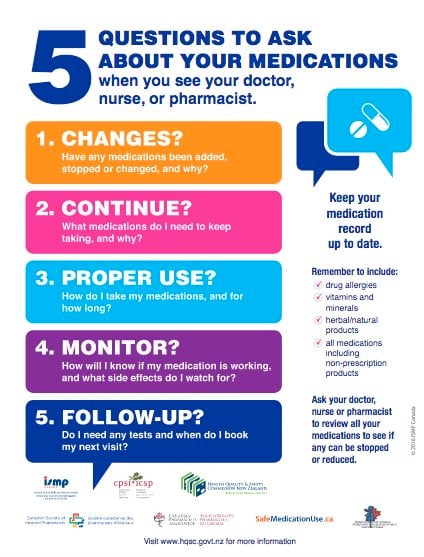

5 questions to ask about your medications(external link)(external link)(external link) Health Quality and Safety Commission, NZ, 2019 English(external link)(external link)(external link) Te reo Māori(external link)(external link)(external link)

Brochures

Medicines and side effects

Healthify He Puna Waiora, NZ, 2024

Health Quality and Safety Commission, NZ, 2019 English, te reo Māori

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust.

Reviewed by: Dr Bryony Harrison

Last reviewed:

Page last updated: