Helicobacter pylori

Also called H. pylori

Key points about H. pylori

- Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a type of bacteria commonly found in the stomach.

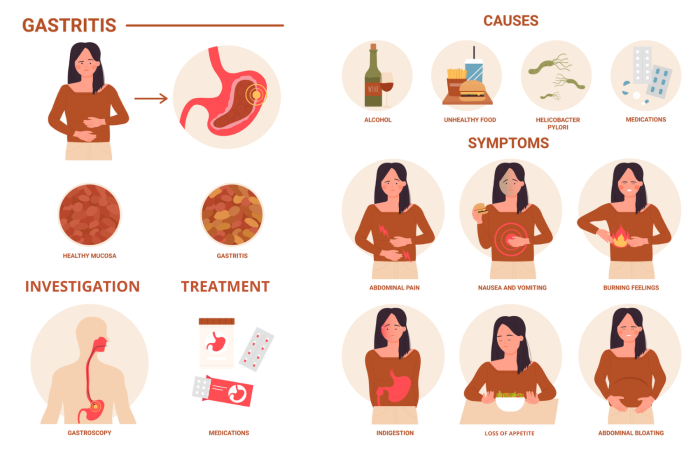

- Most people with H. pylori infection don't have symptoms but some develop gastritis (stomach inflammation) and stomach ulcers.

- Most people pick up the infection in childhood. It’s most likely spread through water and food contaminated with faeces (poo).

- H. pylori infection can be treated with 2 antibiotics plus another type of medicine called a proton pump inhibitor (PPI).

Helicobacter pylori or H. pylori is bacteria that's commonly found in your stomach. It's most likely that it's spread through food and water contaminated with faecal matter (poo).

It's thought that H. pylori infection is usually picked up in childhood. The infection doesn’t go away by itself, but most people never develop symptoms. However, an H. pylori infection can cause digestive problems by damaging the protective lining of your stomach and causing inflammation. This can increase the chance of developing:

- gastritis (inflammation of your stomach lining)

- peptic ulcers (stomach or duodenal ulcers)

- stomach cancer (this is rare).

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the rate of H. pylori infection is lower than in many other developed countries, with an average rate of about 19%. However, this rate varies depending on ethnic group. If you're Māori, Pacific Peoples or Asian you have a higher risk of H. pylori infection than if you're New Zealand European.

Not all people with peptic ulcers have H. pylori. Certain pain relief medicines called NSAIDS, such as aspirin, ibuprofen and naproxen, can also cause ulcers. Peptic ulcers are also more common if you smoke.

Stomach cancer is rare, but Māori and Pacific people have an increased risk. This may be due to the increased risk of getting an H. pylori infection alongside other hereditary and lifestyle reasons.

H. pylori infection is thought to spread from person to person. Most people seem to get it in childhood, probably from their parents or siblings who may not know that they have it as it usually doesn’t cause symptoms.

Ways in which the infection might spread and get into your stomach include:

- touching your mouth after contact with saliva from an infected person, eg, by kissing, or after getting infected saliva on your hands

- touching your mouth after contact with vomit from an infected person

- contact with poo from an infected person, eg, by getting poo on your hands and touching your mouth, or by drinking water or eating food that’s been contaminated by sewage.

There’s a greater risk of spread in areas with overcrowded living conditions, poor hygiene and unsafe drinking water.

Although most people don't have any symptoms, H. pylori infection can cause gastritis or stomach or small bowel (duodenal) ulcers in some people. These can cause symptoms of dyspepsia (indigestion) such as:

- upper abdominal pain

- heartburn

- bloating

- frequent burping

- nausea (feeling sick) or vomiting (being sick)

- poor appetite

- a feeling of fullness after a small meal.

Image credit: Depositphotos

Some warning signs that you need to see a healthcare provider urgently include:

- vomiting blood

- unexplained weight loss

- difficulty swallowing

- black, sticky, tar-like poo.

These symptoms might mean you have a serious complication of H. pylori infection, such as a bleeding ulcer or stomach cancer.

If you have warning signs

If you have symptoms of dyspepsia (indigestion) and any warning signs that you’re at risk of serious complications, such as a peptic ulcer or stomach cancer, you may be referred for a type of endoscopy called a gastroscopy. H. pylori infection can be diagnosed by taking a small piece of tissue (a biopsy) from your stomach during the gastroscopy.

As well as having the warning signs above, there might be other reasons why you might need a gastroscopy. For example, if:

- you’re 55 years of age or older when you first have dyspepsia symptoms, or 45 years or older if you’re Māori, Pacific Peoples or Asian

- you have a family history of stomach cancer that occurred before 50 years of age

- you have unexplained iron-deficiency anaemia

- your healthcare provider can feel a lump in your abdomen (tummy).

If you don't have warning signs

You may not have any of the above warning signs, but have symptoms of dyspepsia (especially if you have heartburn) that don’t get better with lifestyle changes and treatment with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). In this case your healthcare provider will decide how likely it is that you might have H. pylori infection based on the following factors.

- Where you live – H. pylori infection is generally higher in Northland and Auckland regions, compared to the South Island

- Your ethnicity – H. pylori is more common in Māori, Pacific and Asian peoples compared with New Zealand Europeans.

- Where you were born – H. pylori is more common in people born in developing countries.

If you’re considered to be at high risk of H. pylori infection, your healthcare provider will ask for a stool (poo) sample to test for the infection. The test is called a faecal antigen test. You’ll have to stop taking protein pump inhibitors (PPIs) 2 weeks before having the test.

You may also be tested for H. pylori infection if you need long-term NSAID treatment or if you have a family history of stomach cancer. If you take NSAIDs, H. pylori infection can increase your risk of developing peptic ulcers and bleeding in your stomach.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the poo test is the preferred test for diagnosing H. pylori infection, but you must make sure you haven’t been on antibiotics in the past month or had PPI treatment in the past 2 weeks. There’s also a blood test for H. pylori infection, but it’s less reliable and isn’t suitable if you’ve previously been treated for H. pylori infection. A breath test is another method of diagnosis, but this isn’t commonly done in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Most children with H. pylori infection don’t have any symptoms. However, if your healthcare provider has a strong suspicion that your child has peptic ulcer disease, they’ll refer them to a specialist (a paediatric gastroenterologist) for an endoscopy and biopsy. This may be done if your child has:

- pain in the upper left part of their tummy that gets better with eating and that might be more obvious at night

- dyspepsia (indigestion) symptoms that improve with proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment but get worse when the PPI is stopped.

H. pylori infection can be treated by taking 2 antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). The antibiotics kill the bacteria and the PPI reduces your stomach acid so the antibiotics can work well. This combination of medicines is often called eradication therapy.

- The antibiotics used to clear H. pylori infection are clarithromycin plus either amoxicillin or metronidazole.

- The proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) used as part of the eradication therapy are omeprazole, lansoprazole or pantoprazole.

The type of medications used may vary if you have had certain antibiotics before so tell your healthcare provider if you have had any of the antibiotics listed above for other treatments.

You’ll need to take eradication therapy for 14 days. It’s important to take all the medicines exactly as directed and to finish the full 14-day course.

Eradication therapy clears H. pylori in 9 out of 10 people if it’s taken correctly, for the full course. If you don't take the full course of medication, it won’t be as effective in getting rid of the H. pylori infection.

If you still have symptoms 3 months after treatment and a second H. pylori test shows that you still have the infection, you’ll be given a second course of eradication therapy using different antibiotics. Smoking reduces the chance of successful treatment, so it’s very important to stop smoking.

If you have indigestion (dyspepsia) symptoms (see above) due to H. pylori infection you can try the following things to help ease your symptoms.

- Reduce the size of your meals.

- Avoid large meals before bedtime.

- Limit your intake of fatty foods and alcohol.

- Avoid foods that trigger your symptoms, eg, chilli or coffee.

- Lose weight if you’re overweight.

- Stop smoking if you smoke.

- Avoid over-the-counter NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, as these can cause indigestion, heartburn and ulcers.

- Manage stress, eg, try relaxation techniques, mindfulness or cognitive behaviour therapy.

Apps reviewed by Healthify

You may find it useful to look at some quit smoking apps, weight management apps, meditation and mindfulness apps and cognitive behavioural therapy apps.

Once you’ve had successful treatment of H. pylori infection, the chance of being re-infected is very low.

If your symptoms reappear it’s most likely because the medication to get rid of the bacteria hasn’t worked, (eg, if you didn’t take the full course of treatment, or you need different antibiotics) rather than it being a second infection.

How H. pylori bacteria are spread between people is not fully understood, but good hygiene may reduce the spread.

What to do

- Wash your hands with soap and water after going to the toilet and before eating.

- Only eat food that's been washed well and cooked properly.

- Only drink water from a clean, safe source.

Eradication therapy gets rid of H. pylori for most people if it’s taken correctly for the full course. If you don't take the full course of treatment, it’s likely your symptoms won’t get better or might reappear later.

If it’s not treated, H. pylori infection can cause stomach or duodenal ulcers that may bleed and cause anaemia or even life-threatening bleeding. Deep ulcers may burst – this is called a perforated ulcer and may need urgent surgery.

There’s a small increased risk of stomach cancer if you have H. pylori infection.

References

- H. pylori – who to test and how to treat(external link) BPAC, NZ, 2022 (updated 2024)

- Dyspepsia and heartburn/GORD(external link) Auckland Regional HealthPathways, NZ, 2021 (updated 2024)

- Helicobacter pylori infection(external link) NZ Formulary

- Helicobacter pylori(external link) Patient Info, UK, 2024

- How to treat Helicobacter pylori(external link), NZ Doctor, 10 April 2024

H. pylori – who to test and how to treat(external link) BPAC, NZ, 2022 (updated 2024)

H. pylori(external link) B-QuiCK BPAC, NZ

Helicobacter pylori infection(external link) NZ Formulary

How to treat Helicobacter pylori(external link) NZ Doctor,10 April 2024

Webinar: H. pylori update and F.I.T. testing

(Goodfellow Unit, NZ, Feb 2025)

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust.

Reviewed by: Dr Grace Lee, FRNZCGP and Clinical Educator

Last reviewed: