You can now add Healthify as a preferred source on Google. Click here to see us when you search Google.

How and why do viruses change over time?

Key points about viruses and why they change

- It's normal for viruses to change over time and create new variants or strains.

- This page provides information about how viruses work to make us sick, and how they mutate.

- You can also read about how vaccination works with your immune system to help provide protection against disease.

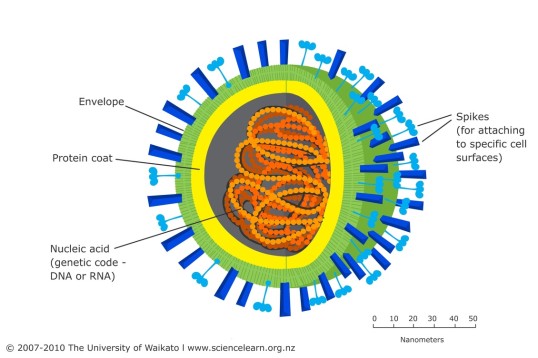

A virus is a tiny organism that is simply some genetic code (DNA or RNA) wrapped in a protein coat. It is a parasite. To survive and spread, viruses need to get inside a living host, such as a human being.

Image credit: Science Learning Hub – Pokapū Akoranga Pūtaiao, University of Waikato, www.sciencelearn.org.nz

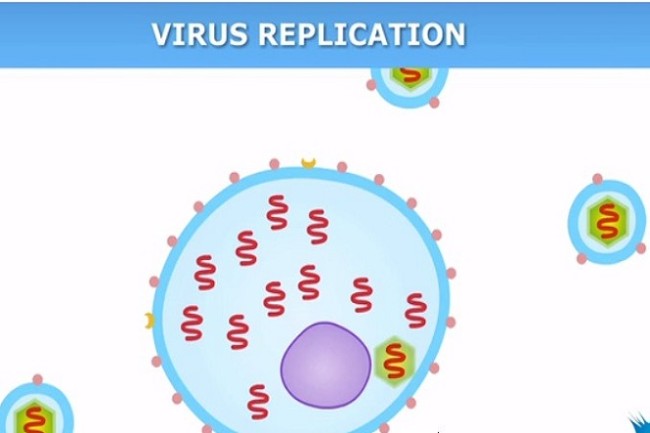

Once inside the host cell, the virus takes over. Its genetic material tells the cell to produce the virus instead of doing what it should normally do. The virus makes thousands and thousands of copies of itself in the cell. This is called replicating itself.

These new viruses then leave the cell and spread to other cells. This is known as viral infection and it can happen within a few hours. Some viruses make you start sneezing, coughing, or vomiting, which helps the virus spread to new hosts.

Common viruses that cause infections in humans include the influenza virus (which causes the flu), varicella-zoster virus (which causes chickenpox), rotavirus and herpes virus.

Your body's immune system identifies anything ‘foreign’. Substances like viruses aren’t supposed to be there, so your body tries to fight them. It can take time for your immune system to destroy a new virus. It has to work out the special characteristics of the virus and then produce antibodies (a type of protein) to destroy the virus.

If you have been exposed to the same virus before your immune system recognises the virus quickly and often destroys it before you have any symptoms.

A mutation is a term for when something changes as it is replicating. A mutation is also called a new strain or a new variant.

Mutations are very common when viruses replicate because they replicate at such a high rate. Some mutations may be minor and could make the virus less infectious, while others may make the virus more infectious.

Over time, your immune system learns how to fight the viral infection. This stops the virus getting into your cells. So, to survive, viruses must adapt or evolve. They do this through mutation.

They are simple organisms and so they often make mistakes when they replicate. This creates changes in their genetic code, which changes their surface proteins. These changes are random. However, with enough changes, your antibodies no longer recognise the virus and so can no longer fight it, and it gets into your cells again.

When a change means the virus gets into a cell, it can start replicating a new version of itself. This mutation is called is a new strain or variant. It is a normal process that happens with all viruses.

Click the image below and scroll down the page to watch this video animation on virus replication.

(Science Learning Hub, NZ, 2014)

Vaccines reduce the risk of getting a disease by working with your immune system to build protection. Vaccines work in different ways, but all show your immune system some recognisable part of the virus, such as part of the protein coat.

When you get a vaccine, your immune system starts producing antibodies to fight that virus. If you are exposed to that virus later, your immune system recognises it and can quickly remember how to fight it.

However, if a virus mutates often, you may need a new vaccine to protect against new strains. This is why you should have the flu vaccination each year, as it is developed to fight off new strains of the flu virus. Read more about how vaccines work.

- COVID-19(external link) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US, 2021

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust.

Reviewed by: Dr Sharon Leitch, GP and Senior Lecturer, University of Otago

Last reviewed:

Page last updated: