You can now add Healthify as a preferred source on Google. Click here to see us when you search Google.

Differences in sex development

Also known as DSD, variations of sex characteristics, sex differences and intersex

Key points about differences in sex development (atawhai taihemahema)

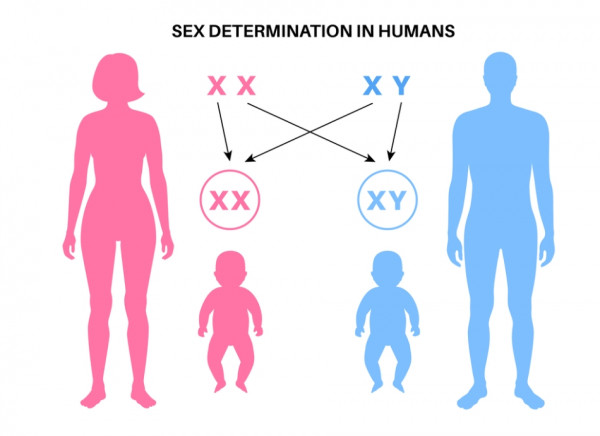

- Babies inherit chromosomes that carry genetic material from their parents.

- The sex chromosomes inherited usually decide if we're genetically female or genetically male.

- Some babies have differences in sex chromosomes or other issues which can lead to different production of hormones so their sex organs develop differently while they're in the womb.

- The word intersex is used to describe these natural variations in external or internal sex organs.

- Initially no treatment or intervention might be needed but some babies will need hormone treatment and some may choose to have surgery later in life.

The genetic sex of a baby is set when they’re conceived. The baby inherits sex chromosomes from both parents, an X from the mother’s egg and an X or a Y from the father’s sperm.

- If the baby inherits the X chromosome from the father, they will be genetically female (XX).

- If they inherit the Y, they will be genetically male (XY).

Image credit: Depositphotos

All babies start off with the same tissue that has the potential to develop into male or female sexual organs. Babies with a Y chromosome make male hormones which make male sex organs develop. Babies with two X chromosomes develop female sex organs.

Sometimes a change in sex development is caused from hormone production in utero (in the womb) by either the mum or the baby that isn't dependant on a sex chromosome (neither X nor Y).

‘Sex organs’ means the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus and vagina inside the body (internal) and the testes (testicles or balls), scrotum (ball sack), penis, clitoris and labia outside (external.) These are also called internal and external genitalia or genitals.

Find out more about how the closely linked urinary and genital systems develop(external link).

Some people can have variations in their chromosomes. Some have extra or fewer sex chromosomes, or a part of the chromosome is missing, or there can be hormonal differences to make their sex organs develop differently.

There are many different intersex variations possible. About 1.7% of the population has one of these variations. The more common ones are:

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH)

- Klinefelter Syndrome

- Turner Syndrome

- Mixed gonadal dysgenesis

- Androgen insensitivity syndrome

- Cryptorchidism

Information about the different intersex variations can be found in a glossary provided by interACT(external link).

Intersex is the ‘I’ in the LGBTQI+ acronym. Sex is biological – for example intersex, female or male. Gender is the way people think and act about biological sex – for example behaviour, activities and attributes people expect from girls or boys. Sexual orientation is the sexual attraction to male, female, none or both.

Often DSD is picked up at birth, and sometimes before birth, if there are visible differences in sex characteristics. Examples include:

- Babies who are genetically female (XX) but who have:

- a large clitoris that looks more like a penis

- labia that are closed or folded and look more like a scrotum

- lumps inside closed labia that feel like testes.

- Babies who are genetically male (XY) but who have:

- a variation in the urethra (tube for urine and semen) where it doesn’t reach to the end of the penis

- an unusually small penis with the opening of the urethra close to the scrotum (ball sack)

- missing testes

- undescended testicles and an empty scrotum that looks like labia.

Some types of DSD may not be diagnosed until puberty when further physical development is expected to happen. An example is when somebody with a different chromosome pattern (eg, no X chromosome) has female sex organs but doesn’t start having periods.

If your baby has undescended testes or their genitals look different, you may be asked about your family and reproductive history. Your baby may have tests so healthcare providers can make a diagnosis and find out if any treatment is needed.

Tests could include:

- a specialist examination

- an ultrasound scan to look at their internal organs

- blood tests to check chromosomes and hormone levels

- urine tests.

You can cuddle your baby, give them a nickname and love them straight away. Once your baby has been examined and had any necessary tests done, your healthcare team will support you to decide about what you would like to do about gender while raising your child. While they can provide you with information and support, it's your choice and there’s no hurry to decide. However, like any other child, as your tamariki grows up they may want to choose their own gender and it may be different to what you decided for them when they were born.

What about their birth certificate?

You can register your baby’s birth with their sex listed as indeterminate in Aotearoa New Zealand. Whatever is entered on the birth certificate can be changed later on by the individual or by a parent or guardian. Read more about changing the registered sex on a birth certificate(external link).

If your intersex baby doesn’t have any physical problems that need immediate treatment there may be no need for any treatment or intervention. It may take a while for tests to be completed and for you to fully understand their DSD. It’s best to wait and see what happens for a while, and adjust to what was probably an unexpected finding.

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is a genetic (inherited) condition where the adrenal glands (walnut-sized organs above your kidneys and part of the endocrine system) don’t produce hormones as they should. As well as affecting the appearance of genitals it can cause faster growth, early puberty, fertility issues and shorter than average height. There are 2 forms, classic and nonclassic.

Classic CAH

Classic CAH is less common and always needs hormone replacement medicines straight away to replace naturally low hormone levels. These will have to be taken every day. Classic CAH can result in an emergency situation called adrenal crisis due to low levels of cortisol and/or aldosterone hormones. It can start within the first few days of life or later after an infection or physical stress. It needs to be treated urgently.

If your baby or child has classic CAH, there are signs to watch out for that tell you they need immediate treatment. These include:

- dehydration or poor weight gain

- hypoglycaemia (low levels of blood glucose)

- ongoing jaundice (when skin, whites of their eyes and mucous membranes, eg, inside their nose and mouth, turn yellow).

If your pēpi or tamariki has DSD and these symptoms contact your healthcare provider urgently.

If your child has CAH they are likely to be referred to a paediatric endocrinologist (a specialist doctor who works with hormone problems in children). A team of health professionals is likely to be involved in their care, including:

- a urologist to treat urinary conditions or their kidneys, bladder or urethra (wee tube)

- a mental health professional (psychologist)

- a geneticist (gene expert)

- a reproductive endocrinologist.

Nonclassic CAH

People with nonclassic CAH may not show differences of sex development when they are born. They may have early puberty, shorter stature than their parents, bad acne, irregular periods or trouble getting pregnant. It doesn't always need treatment.

Medicines for other forms of DSD

People with other forms of DSD may also benefit from hormone treatment to correct imbalances or help with fertility or appearance.

Surgery

Your healthcare team will discuss the importance of not removing any part of your child’s body that they may want later. Surgery in childhood is only used if there are problems with continence, frequent infections or a risk of organ damage, cancer or death.

As your child grows old enough to make decisions about gender they can be involved in discussion about any possible reconstructive surgery.

Mental health support

Support is an important part of treatment. Look for a mental health professional who has experience working with intersex people and/or parents of intersex children. A psychologist can help you understand what’s happening and that being intersex is part of natural variation in sex characteristics. They can also support you, and your child, with information and conversations about sexuality, relationships and body image.

Some types of DSD can affect people in other ways as well, eg, their growth, heart, kidneys and fertility. Your healthcare team will discuss this with you.

Intersex support for parents(external link) Private Facebook group

DSD families website(external link) UK

Intersex Aotearoa(external link) NZ

VSC – a practical guide for parents in Aotearoa NZ(external link) Promoting healthy and positive outcomes for people born with a variation in sex characteristics (VSC)

How sex development works(external link) University of Toronto, Canada

Brochures

A support guide for parents of intersex rangatahi – your child is a taonga(external link) Intersex Aotearoa, NZ

Hormones and me CAH(external link) Australia and New Zealand Paediatric Endocrine Society

My intersex self(external link) Intersex Trust Aotearoa New Zealand

Intersex awareness(external link) Intersex Aotearoa, NZ

What is intersex? Rainbow definitions(external link) Pride Pledge, NZ

Intersex variations glossary – people-centered definitions of intersex traits and variations in sex characteristics(external link) interact Advocates for Intersex Youth, US

A girl’s guide to CAH – by Emma(external link) Living with CAH, UK

All about intersex(external link) Intersex Youth Aotearoa, NZ

Know your rights – a guide for parents(external link) Advocates for Informed Choice, Canada

References

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia(external link) Mayo Clinic, US, 2024

- Ambiguous genitalia(external link) Mayo Clinic, US, 2018

- Ambiguous genitalia and disorders of sexual development (DSD)(external link) University of Texas Medical Branch Health Pediatrics, US, 2019

- Change the registered sex on your birth certificate(external link) New Zealand Government, NZ, 2023

- Differences of sex development – atawhai taihemahema(external link) Starship, NZ, 2020

Differences of sex development – atawhai taihemahema(external link) Starship, NZ, 2020

Webinar

Intersex health – community support and patient centred care(external link) Intersex Aotearoa, NZ

Brochures

Hormones and me CAH

Australia and New Zealand Paediatric Endocrine Society, 2024

A support guide for parents of intersex rangatahi – your child is a taonga

Intersex Aotearoa, NZ

All about intersex

Intersex Youth Aotearoa, NZ, 2017

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust

Reviewed by: Dr Ronnie Stein, Paediatric Endocrinologist

Last reviewed: